Food & Drink

A Taste for the Hunt

A boy acquires a profound appreciation for the hunt

Photo: Erika Larsen

The greatest meal of my life involved a Triscuit.

At the age of eleven, you see, I came into possession of a .177-caliber Crosman air rifle. The rifle shot mushroom-shaped lead pellets, and if you pumped the rifle a dozen times or so, to the point that a pneumatic/mechanical explosion felt dangerously imminent, it shot them pretty hard. One afternoon, bored with plinking cans, I took lazy, purposeless aim at a mourning dove perched upon a branch in the next-door neighbor’s yard. Perhaps I meant to scare it, to startle it skyward, I don’t know. In any case I felt certain I couldn’t hit it.

I hit it. The way the dove dropped, in an awful flutter of wings, mirrored the state of my insides; my heart collapsed in free-fall panic. As a boy of the suburbs, I’d never killed anything before, or even considered it; my imaginary targets had always been Nazi infantrymen. I leaped the concrete-block wall dividing our yard from the neighbor’s, only obliquely aware, at that moment, of how severely forbidden was this terrain. (The neighbor was a middle-aged mumbler, schizophrenic if you trusted neighborhood rumor, who was fond of sunbathing nude on the roof.) No matter: I dashed across his backyard to where the fallen dove was flailing in the shade. Desperate to end its misery, I pumped the rifle to its airy maximum and shot the dove point-blank in the head. The stillness that followed didn’t console me. My eyes soaked, I shot it again, and then again, sobbing, and then again and again until I was finally out of pellets.

I could have left it, or buried it. But something inside me, with a wise and moral voice like Obi-Wan Kenobi’s, said I had to eat it. Wasting it, said the voice, would only compound the sin. As a latchkey kid, as we were called in those days, I’d become proficient at making Triscuit pizzas in the broiler, to feed myself after school, but this recipe, cadged from the Triscuit box, marked the beginning and end of my cooking chops. With a pocketknife, then, I cut the dove open, not knowing what to look for but finding a small wedge of purple breast meat from which I carved a few mangled slices. I heaped them atop some Triscuits and watched them sizzle under the red electric coil, my tear-smeared face staring back at me from the oven glass. And then, alone at the breakfast counter, I ate them.

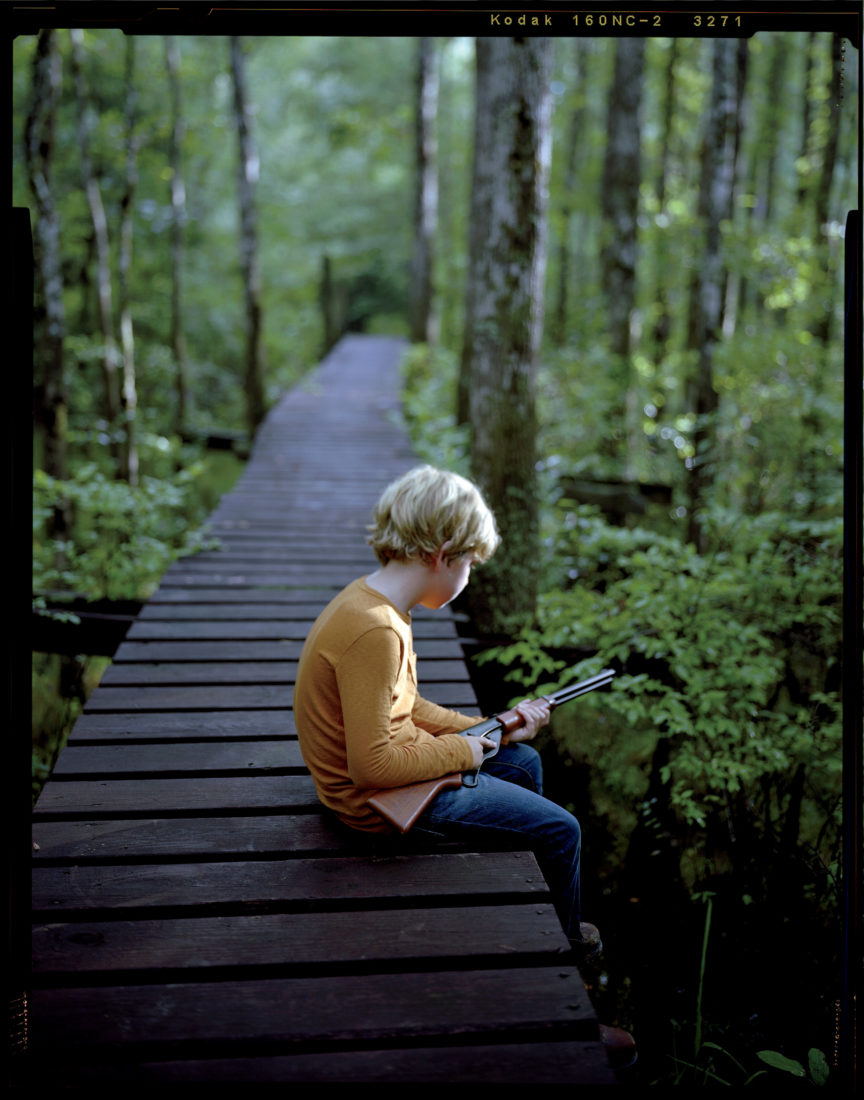

Photo: Erika Larsen

Like Father, Like Son

A quiet time in the woods.

I don’t wish to overstate the moment, but the greater risk, it seems to me, lies in understatement. With each sniffling, tentative bite came an ever more profound understanding of the natural world, an epiphanic realization of what it meant to eat meat, to eat flesh, to eat animals, of the way death begets life, the way death feeds and nurtures life, of the cruel and beautiful order under which we all operate, boy and dove alike. If design, as the teleological argument goes, is how God makes His presence known, then here at the breakfast counter was God, speaking to me from a Triscuit pulpit. And though I wept throughout that meal, in hot shame and terror, something else occurred to me as well, a sensation at once irreconcilable but undeniable: The dove breast, seared from the broiler, unadorned with even salt and pepper, was…delicious. Here was pain, at seeing the world’s dark heart revealed, but here, too, was a new and riveting pleasure, a taste unlike anything I’d encountered before.

For almost thirty years now I’ve been trying to re-create that meal. With doves, of course, shot over sunflower and millet fields in Mississippi and Georgia, but with ducks too, lifted gently from the mouths of wet Labrador retrievers in the Arkansas Delta and elsewhere, and with wild turkeys, and with squirrels, and with a musky-flavored wild boar I shot in the Tennessee mountains, and plenty of deer as well: all in the service of a single memory, a singular truth. Just recently I read about Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s vow to only eat the meat of animals he’s killed himself, which he’s been doing on a California farm. This is commendable, if a bit unwieldy (he can expect some awkwardness while traveling), and may just be the next logical frontier in the locavore and ethical-eating movements that have been blessedly spreading throughout the nation. For hunters, however, this is no frontier. It’s something every hunter comes to understand, whether by shooting his or her first squirrel under grandfatherly tutelage (as my eight-year-old son plans to do this fall, with his Pop), or accidentally shooting a dove over a concrete wall: that only by killing, by enacting (or at least observing) the transformation of animal to meat, can we own up to our appetites with anything like honesty. “Man is a fugitive from Nature,” wrote the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, and, as we all know, the fugitive’s life is necessarily constructed upon lies. Meat is not an abstract protein; that’s the lie, subconscious but toxic all the same. It’s the lie we abet every time we toss out a cellophane-wrapped package of meat that went neglected in the refrigerator’s way-back, stung by the waste of money if stung at all. For the thoughtful hunter there is no such blitheness. Grandiose though it may sound, the hunter afield is stalking more than game; he’s stalking truth.

But why wild truth? This is where pleasure bleeds in, admittedly, but also something deeper. It’s become fashionable of late for restaurateurs to extol the provenance of the meat on their menus—what farm the pig came from, who fed it—in order to tell a story of how that pork shank made its way onto your plate. These have become the dinnertime equivalent of bedtime stories, designed to lull you into virtuous enjoyment. And while they’re a necessary corrective after decades of industrial storylessness, these stories are inevitably about the farmer, not the animal. What we hear about the animal is what was or wasn’t done to it. With wild animals, it’s different. The story belongs to the animal, except for the ending, when the story turns briefly to the hunter. At a deer-hunting camp I used to frequent near Crystal Springs, Mississippi, we used to perform something we called “the autopsy.” The idea was to determine just how the deer had died—where the bullet had hit, what precisely it had done—but, out in that low-ceilinged tin shed, gathered around a pendent whitetail carcass, our whiskey breath visible in the autumn-chilled air, we’d learn a whole lot about its life, too: what it’d been eating, what the scars on its hide revealed, how that hairline fracture on its hind leg was what had prevented it from springing away fast enough to beat a clumsy shooter. This is not to suggest we lounged about the deer camp telling stories about our deer in the sacred manner of movie Indians. Of course not; we told dirty jokes like everyone else. But it is to say that the deer were present, not as mere meat, commodities, or God forbid trophies, but as wild and sentient creatures whose lives we had deigned to take—hungrily, but respectfully.

The flavor of game, like its story, belongs to the animal, not to any farmer, and not to the hunter (unless he botched the field dressing or some such). It’s contingent on its diet, its age, its sex, its life, and it’s owing to this that the flavors can vary so widely, so maddeningly. Yet there’s an elemental magic to those free-ranging and often untamable flavors, a direct link to the natural chaos that lies within that grand design I happened upon as a weepy eleven-year-old boy. For a cook, this can be challenging: It took me months to devise methods of making that ancient Tennessee boar edible, and despite valiant and repeated efforts I have yet to charm guests with a bite of Canada goose. Yet this is somehow part of the allure, too. Into the kitchen with game comes wildness, with its infinite degrees of diversity and complexity, and its infinite mine of stories. This is why the oxymoronic farm-raised game is such a wan replica of the genuine article: Its life and death are predetermined, its story not its own. “Poetry,” said the French critic Denis Diderot, “must have something in it that is barbaric, vast and wild.” As a Triscuit once taught me, the same goes for eating.