Outdoors

Force of Nature: How Dr. Drew Lanham Is Changing Birding

The South Carolina ornithologist’s enthusiasm has brought the pursuit—and its connections to history and race—to a new audience

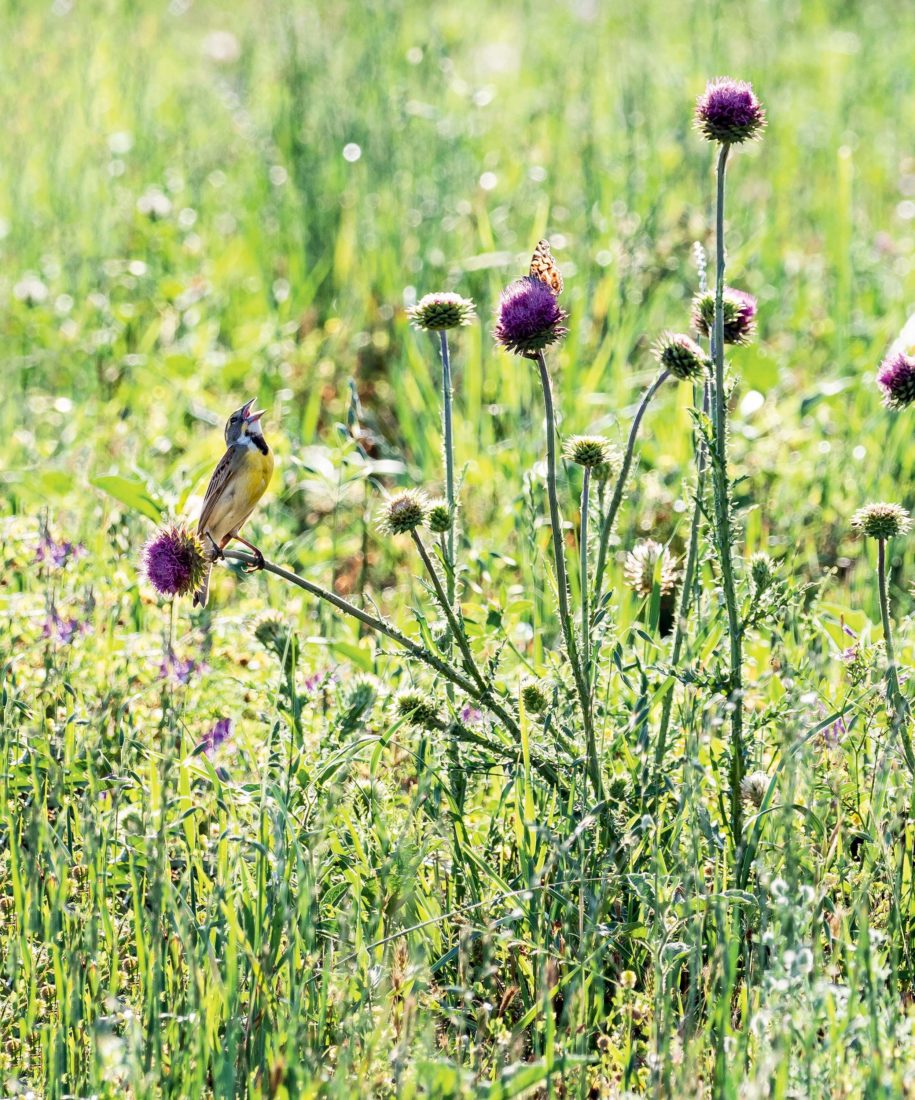

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Dr. J. Drew Lanham bird-watching in Pendleton, South Carolina.

Beneath a heavy sky, swells of powdery yellow and blue wildflowers roll in a sea of high grass. Pale butterflies flit in and out of the growth as if the field is at a boil. Perched above it all, watching, its dark form silhouetted against the clouds, a red-winged blackbird stands atop a fence post, singing.

“You listen long enough and you get some idea there’s joy to it,” J. Drew Lanham says, a long-lens Canon pressed to his eye. He pushes the shutter release, and the camera shoots off a rapid burst of frames. “I may anthropomorphize a bit, but I hear joy in birdsong.”

It’s easy to hear joy today. A weeklong rain that’s been parked over Upstate South Carolina has paused for a few hours, giving us this chance to go birding. We’re at Simpson Station, an agricultural research center in Pendleton operated by nearby Clemson University, where Lanham—one of the South’s most celebrated ornithologists—holds an endowed chair as an Alumni Distinguished Professor of Wildlife Ecology. It’s in Clemson’s classrooms that Lanham lectures about wildlife, forest management, and conservation, but it’s here, along this stretch of pasture straddling the Three and Twenty Creek, that he finds his inspiration. “If I don’t get out here, the day’s just not going to happen,” he says. “It’s like coffee.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

A blue grosbeak.

He values the quiet of the place, the play between open fields and water, the long vistas from which you can see the mountains when the sky is clear, and of course, the birds: indigo buntings, black-and-buff bobolinks, wild turkeys, eastern meadowlarks, grasshopper sparrows, blue grosbeaks, eastern phoebes, sometimes even a scissor-tailed flycatcher. “And,” he adds, “I can come here and not be harassed by a racist farmer.”

Lanham isn’t stereotyping—he’s talking specifically about a man who recently pulled up beside him while he was out birding and told Lanham about the “niggers who used to pick cotton” in the area and then mentioned, pointedly, that he was carrying a gun. It’s the type of interaction Lanham, unlike most other birders in the world, must sometimes navigate, because Lanham is a black man in South Carolina, and birding, as he says, is “one of the whitest things you can do.”

Raised in Edgefield, South Carolina, just north of Augusta, Lanham traces his roots to a slave named Harry who was brought to the area around 1790. The birthplace of ten governors, as well as (and often including) noted racists and segregationists such as “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman and Strom Thurmond, Edgefield was also home to the two-hundred-acre Lanham family farm nestled deep in the Sumter National Forest in a district called the Long Cane. There, near the Savannah River amid a piedmont dotted with plants with evocative names like adder’s-tongue, yellow sunnybell, streambank mock orange, and shoals spider-lily, Lanham spent a youth falling in love with nature. “Every bird was my thing when I was a kid,” he says. Pecan-thieving blue jays, wild turkeys, too-smart crows, even the hooting owl that so spooked his grandmother Mamatha that she shot a hole through the porch roof trying to get at it one night—they all drew Lanham’s interest in a profound way. He took particular pleasure in flushing bobwhite quail from the brush, but his fascination was not selective. “Any bird that would show itself to me, I wanted to see it.” A few times he even lay on his back in the pasture lane, remaining still long enough to draw buzzards, curious to see if he was really dinner or not.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Lanham birding at Simpson Station.

After a childhood spent racking up library fines for overdue titles such as Fifty Birds of Town and City, Lanham found himself studying mechanical engineering as an undergrad. As a black kid who was good at math and science, he says, it was one of two options presented to him: physician or engineer. He did well in his studies but felt like he “was rotting on the inside.” Finally, in what he says was perhaps his “most courageous act,” he switched his major to zoology. “I lost my full-ride DuPont scholarship and found my life.” Before long he was jumping through all the “right hoops”—PhD, publications, and tenure, eventually gaining enough prominence to earn a seat on the National Audubon Society’s board of directors.

Yet while his research into such ornithological mysteries as the unusual sex life of eastern bluebirds, or the monotypic nest site selection by Swainson’s warblers in the mountains of South Carolina, was yielding publications and strong results, Lanham still found himself asking just who and what his work was affecting. The exercise of “scientific sausage making,” as Lanham puts it—the collection of data used in statistical models in a lab, where the findings often seemed to remain—led him to question if there were other ways to make a difference in the wider world of conservation while reconnecting with the roots of his passion.

Soon he began writing outside the modes of academia, penning essays and poetry, and eventually, in 2016, published a memoir, The Home Place, which won the Southern Book Prize and the Reed Environmental Writing Award from the Southern Environmental Law Center. He recently released his first collection of poetry, Sparrow Envy, and is on his way to becoming the poet laureate of Edgefield County. He’s also written for magazines and publications such as the New York Times and Orion, for which he composed a piece called “9 Rules for the Black Birdwatcher,” including rule number three: “Don’t bird in a hoodie. Ever.”

In the science world, Lanham says, there’s been some disbelief and discomfort in regard to his shift toward the literary. Eschewing hard data for the kind of results that you “can’t break down with statistics” is far from the traditional path for a scientist. At the same time, Lanham says, he’s experienced “amazing acceptance and willingness to listen” from readers. His work has been shared so widely, both through social media and traditional outlets, that I recently heard a friend describe him as “NPR famous.” Encountering his perspective on what it’s like to be a black man interacting with the natural world has, for many people, been the first time they’ve heard someone connect nature and race. He often hears personally from readers now, reactions that, he says, he “would never, ever get from science.” And though these appreciations come from people of all races, Lanham points out that “many people of color have told me what a difference my writing has made to them. They say, ‘You’ve been able to voice something I’ve been feeling for a long time.’”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

The professor in his backyard creative space, “the Thicket.”

As we rumble up a new stretch of gravel at Simpson Station, Lanham keeps his eyes peeled for a dickcissel—a Midwestern bird that nevertheless chooses to make its home here because of the open, prairie-like fields. From a distance, if someone was watching us through the eyes of, say, the red-tailed hawk that flew by earlier (which, from at least three hundred yards away, Lanham identified in half a glance), we must look like a couple of good ol’ boys out mudding, because Lanham has driven us here in his 1986 Ford Bronco II, its whole body painted camouflage. The back windshield is festooned with stickers of antlers and leaping deer. Lanham bought it for $1,800 off the Internet. He calls it his “incognegro mobile.” “I imagine it as a cloak of invisibility,” he says, a huge grin on his face. “It allows me to get to things unseen.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Lanham with his “incognegro mobile.”

Thus far today, the only people who have gotten close enough to see through its windshield are two young agriculture students passing in their pickup trucks, fingers raised from steering wheels in the classic Southern salute, but now another pickup is driving toward us and this one is slowing. I think of the story of the farmer Lanham told me earlier, and as the truck rumbles to a halt beside us, I see a weathered white man behind the wheel wearing a grizzled beard and a dirty baseball hat.

“Hey!” Lanham says, at once easing my trepidation. Not only do the two men know each other, they’re friends and kindred spirits. The man is a facility manager here, and, within minutes, is deep in a discussion with Lanham about a mutual passion: deer hunting. Lanham sees hunting as yet another chance to connect with nature, an almost sacred opportunity to tap into our roles as animals within its complicated networks. He invites the man to join his hunting club (“It’s in Buzzard Roost. You ever heard of Buzzard Roost? If you want to join, let me know. I know the president…”). They discuss the protein content (40 percent!) found in cottonseed used as livestock feed, and in response to a question about how many cattle are held at the station, the manager says, “I’ve stuck my arm in two hundred and ninety-four cows this year, so…” It’s a variation of conversation that’s probably happened a few billion times between people who love and work the land, though I wonder just how many of those exchanges have ever included a black turkey-hunting ornithologist poet in rural South Carolina.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

A dickcissel, one of Lanham’s favorite birds.

“Being able to talk through truck windows—that’s critical,” Lanham says as we continue on. “That acceptance, that’s huge.” He extends that consideration to the dickcissel, which soon appears right where Lanham had guessed it would. “It’s about acceptance,” Lanham says as the tiny yellow-chested bird sings out an insect-like bzzrrrt bzzrrrt bzzrrrt, “when a bird that’s not supposed to be here finds it accepting and welcoming…” It’s almost as if he’s speaking of himself. This is a pattern with Lanham. He links birds to his life and to culture and then back again with an offhand elegance.

“Birding is not what you can ID through binoculars,” he says. “It’s a feeling, an immersive understanding of all that’s around, thinking of the history of the people and the land.” These correlations weren’t always something Lanham wanted to highlight, though.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Lanham, on the hunt.

“Initially, I didn’t want to talk about race,” he says. He wanted the science behind his work to do all the talking—the data collection, the crunched numbers, the hours of observation paying off in airtight scientific conclusions. But this, he found, was easier said than done. The science of birds inevitably led back to the land, which then proved intrinsically tied up with the life of humans. “Particularly in regard to the South,” Lanham says, “there’s little separation between the life of birds and the life of people.”

A few years ago, while birding on a rice marsh in the Lowcountry, Lanham overheard a woman comment about how good a job the Department of Natural Resources did of maintaining the rice fields. It was a moment of realization for Lanham—that the woman had no idea that the habitat was in fact created by enslaved people moving almost unthinkable quantities of pluff mud by hand. Yes, Lanham thought, the DNR does do a good job, but it wasn’t the DNR that actually created the habitat for the birds we’re watching. And it wasn’t Mother Nature, either. It was slaves.

By speaking about this context—like this thread drawn from rice to people to birds and to culture—Lanham hopes he can give nature lovers new ways to read the wild. “So when someone sees a black duck,” he says, “or a black rail on a rice marsh, they might have in mind a vision of the black people who changed the world.”

But more than connecting dots about humanity’s complicated impact on the landscape, Lanham seems driven most of all by a simple and overwhelming love of birds. “Yes yes yes!” he says, raising the camera to his eye. “That’s an indigo bunting!” He starts taking more pictures, his camera clicking away. “Look at that! That bird is so blue!” This impulse isn’t confined to the outdoors, or even to real birds. Earlier, in a coffee shop, I heard him asking about a bird at the counter and turned to see what had flown in, only to find him taking photos of an origami crane.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

An indigo bunting.

Lanham is fifty-three, and his enthusiasm for the natural world seems as strong as it ever could have been. As his camera fires off, I wonder how many pictures of birds he has taken in his lifetime. If he’s even had the chance to look at them all.

Lanham counts fewer than ten other black birders he’s met personally but makes it a point to clarify that love of nature is not restricted by race. “I’m certainly not the first black person to appreciate birds,” he says. “Black folk have always had connections to nature—unfortunately, some of those have been forced, and part of that is what we’re still contending with.”

The red-winged blackbird is singing near us again. It seems to be following us. Or letting us follow it. Lanham watches, in no rush at all, even as the rain starts to fall. He says that he often misses meetings when he’s out here, letting the hours flit away on the wind.

“He can sing all day long,” Lanham says, watching the bird. But once again I’m finding it hard to tell if he’s talking about the bird or himself. “You sing from any post that suits you.”