Toni Tipton-Martin used the image of a red bandana to start a journey that has tied her to a different way to see and understand the American food story.

Tipton-Martin was raised in Los Angeles and worked as a nutrition writer at the Los Angeles Times before becoming the first African American food editor of a daily newspaper, at the Cleveland Plain Dealer. A founding member and former president of the Southern Foodways Alliance, Tipton-Martin has lived all around the country, including Austin, Texas where she founded the SANDE Youth Project, a nonprofit aimed at combating childhood obesity. These days, Tipton-Martin lives in Baltimore, where she and her husband are restoring a nineteenth-century rowhouse.

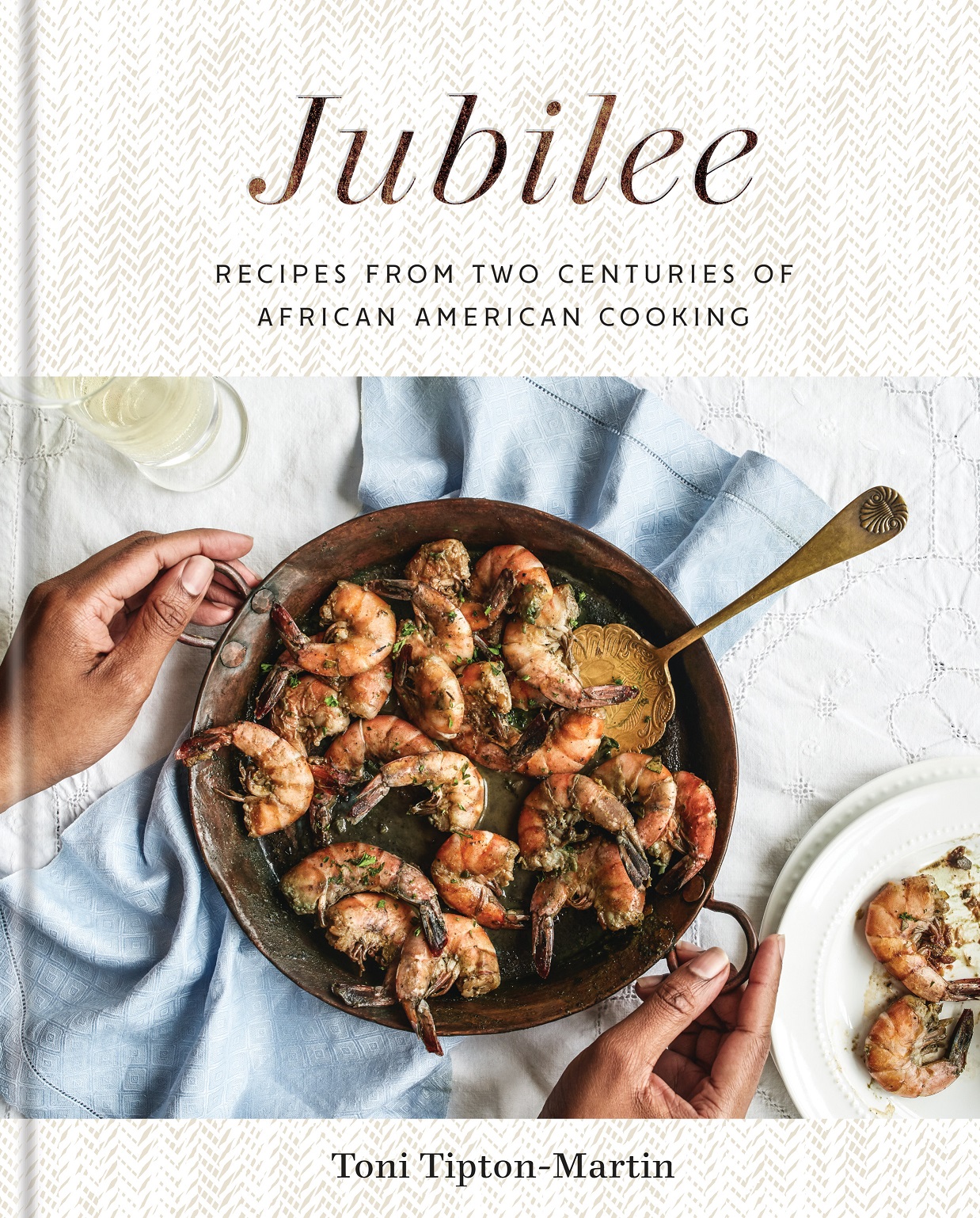

Her real work, though, has been a different kind of restoration. Following on her award-winning book, The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, which documented rare and little-known books by African American chefs, Tipton-Martin is this fall releasing Jubilee: Recipes From Two Centuries of African-American Cooking. Lushly photographed and richly researched, Jubilee builds on Jemima Code’s foundation by highlighting more than one hundred recipes that capture the complex roots of African American cooking, from celebrations and parties to everyday family suppers.

“The material was so complex that I needed to ease it out a little at a time,” Tipton-Martin says. “You don’t eat an elephant all at once.”

Both books can trace their beginnings back by more than a decade, to when Tipton-Martin was becoming troubled by a feeling that the image of Aunt Jemima wasn’t the real story of African American contributions to the nation’s culinary traditions. She wasn’t so much disturbed by the image grinning from boxes of pancake mix and bottles of syrup as she was by what Aunt Jemima represented—the too-easy stereotype of enslaved black cooks that had overshadowed a long history of talented black chefs, cooks, caterers, and cookbook authors. Around 2008, at the annual Southern Foodways Symposium in Oxford, Mississippi, Tipton-Martin arrived with sheets of stickers of Aunt Jemima’s red bandana, adhering them to people’s name tags while she talked about her new blog, The Jemima Code Project, where she was gathering the stories of African American cooks.

“I took [that project] to the internet kicking and screaming,” she says today. “I had no desire to write in the first person or to make this part of my story. I was a reporter on a mission. I was purely looking for my grandmother on the pages of Southern food history. Digital media created an opportunity for my voice to be heard.”

The project that would come to dominate her life. Her research led to years of digging in archives and libraries, where she discovered cookbooks written by black cooks as early as 1827. She started gathering those books, diving into book auctions, and haunting book stores. Eventually, Tipton-Martin built an exhibit that toured museums and historic sites. That led, finally, to a book about the books. The Jemima Code was published in 2015 and went on to win a James Beard Award. By finding and giving serious attention to unknown or forgotten chefs, Tipton-Martin helped to widen the story of American cooking, bringing new attention to black culinary entrepreneurs.

Tipton-Martin wasn’t finished, though. There was more to be found in her book collection: There were recipes. The Jemima Code is more of a reference book than a cookbook, although the books she wrote about included plenty of recipes. Stretching from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, many were obscure, with sketchy directions and ingredients that had all but disappeared. Tipton-Martin tested and updated, studying how the recipes could be a bridge between history and the contemporary lives of cooks today.

To work with such old recipes, Tipton-Martin ended up doing what she calls “modern adaptions” that appear side by side with the originals. We talked to Tipton-Martin about the new book, the work that led to it, and the complexities of these culinary and cultural histories.

You use a fascinating process of showing the original, historic versions alongside your modern, adapted versions of dishes. What did you have to change the most from the originals?

Depending on how far back the recipe went, I had to flesh it out. These are recipes that were written by women who believed everyone had the same understanding of the elements of cooking. So they were comfortable saying “Bake a cake in the usual way” or “First you make a roux.” Back then, they were the cooks and everyone they knew were cooks, so they thought, well, everybody knows how to do that. I had to try numerous versions numerous times to ensure I was getting their way right, not whatever my expectation or the modern reader’s expectations would be.

People can come to these recipes and say, “Well, that’s just a standard macaroni and cheese.” If I gave the recipe with the béchamel sauce, the way that a cook who had all day to prepare it would have, people wouldn’t recognize it.

Did you make the original versions? Were recipes like the “homemade coffee,” with cornmeal, molasses, and bran, even possible to make?

In the beginning, when we thought it was going to be more of an African American recipe bible, hovering around 600 recipes, I actually went out and gathered dandelions in the neighborhood to make dandelion wine. And I wanted to do that just as an exercise, for my own knowledge. That’s how we came up with the idea of shadowboxing the original recipes. Then we didn’t have to be accountable for trying to find ‘ribbon cane syrup’ or the kind of molasses that would have been left at the bottom of the pot.

Lamb is often skipped over in Southern cooking, but you devoted a whole section to it. Was it that common in black cooking in America?

Mutton was. And goat is in Jamaica. What I wanted to do was thread the needle for people to understand that some of the dishes that appear on our tables today can be traced to the diaspora. They’re not all rooted in the Southern style. That lamb was a point of contention—most people aren’t familiar with it as a standard African American dish. And that’s the way the recipes in Jubilee stand out against Southern and soul. It isn’t because they’re going to be overtly fancy or cheffy. Some are unexpected.

When you started the original Jemima Code project, you were looking for history that went beyond the caricatures that had shaped so much of the story of Southern cooking. When we talk and write about black contributions to cooking in the South, why do we tend to stay away from a narrative that goes beyond enslavement and poverty?

Written evidence of African American cooking is hard to find. On top of that, history hasn’t given much credence to the idea that there’s been a black middle class and elite. To attribute any accomplishment to black food professionals first requires acknowledging their existence. That just doesn’t fit the narrative that we as Americans keep telling ourselves and the way blacks are portrayed in the media, whether that is continually showing our males as criminals, our women as welfare queens, our children as illiterate. The broader community comforts itself with notions of supremacy that make it hard to contend with someone who communicates and functions on your level. I imagine it will be easier to expand the culinary narrative beyond enslavement and poverty with more evidence of African American accomplishments.

Is there a place to talk about black and white foodways coming together in the American cooking story?

Absolutely. There is definitely a place to hold conversations about equity at the table, and we started them during gatherings of the Southern Foodways Alliance. Back then, we intentionally cultivated a safe space for these complex conversations that began with open minds and education so it felt less territorial. When we have entered a place where we trust the space and the people and the process, then we’re more likely to come away from that conversation, as we did, with just one thought changed.

The trouble is, once those conversations move to social media, guardrails were removed. Now people say the first things that come into their minds, without recalling grandmother’s wisdom: There is a difference between using one’s inside voice and one’s outside voice. On social media, we’re firing off these immediate tweets—witty complaints and heartless criticisms that can create more barriers than before. People are now digging in with their tribe and defending their ground. We have more opportunities to voice our opinions, but we’re voicing them so strongly that the hearer(s) may have difficulty listening.

Over the years, what’s the book that’s gotten away? Is there one book you’d consider the highest prize if you found a copy?

I paid the highest price already, and that was Abby Fisher’s What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking (published in 1881). I remarked on social media that it was coming up for auction and I was going to need $10,000 to even play. . . Followers and friends begged me to start a Go Fund Me, which I had a negative reaction to—journalists don’t take anything for free. But people insisted. We raised $10,000 in 10 days. It wasn’t enough. I was outbid—[the copy is] at the New York Public Library. I was devastated, but I promised everyone I would sit on that money until the book became available again. It did about a year ago. It was one of the scariest moments of my life to pay that kind of money for an artifact that is disintegrating before my very eyes. I’ve become a little nervous about being a collector now. [The books] have become so expensive.