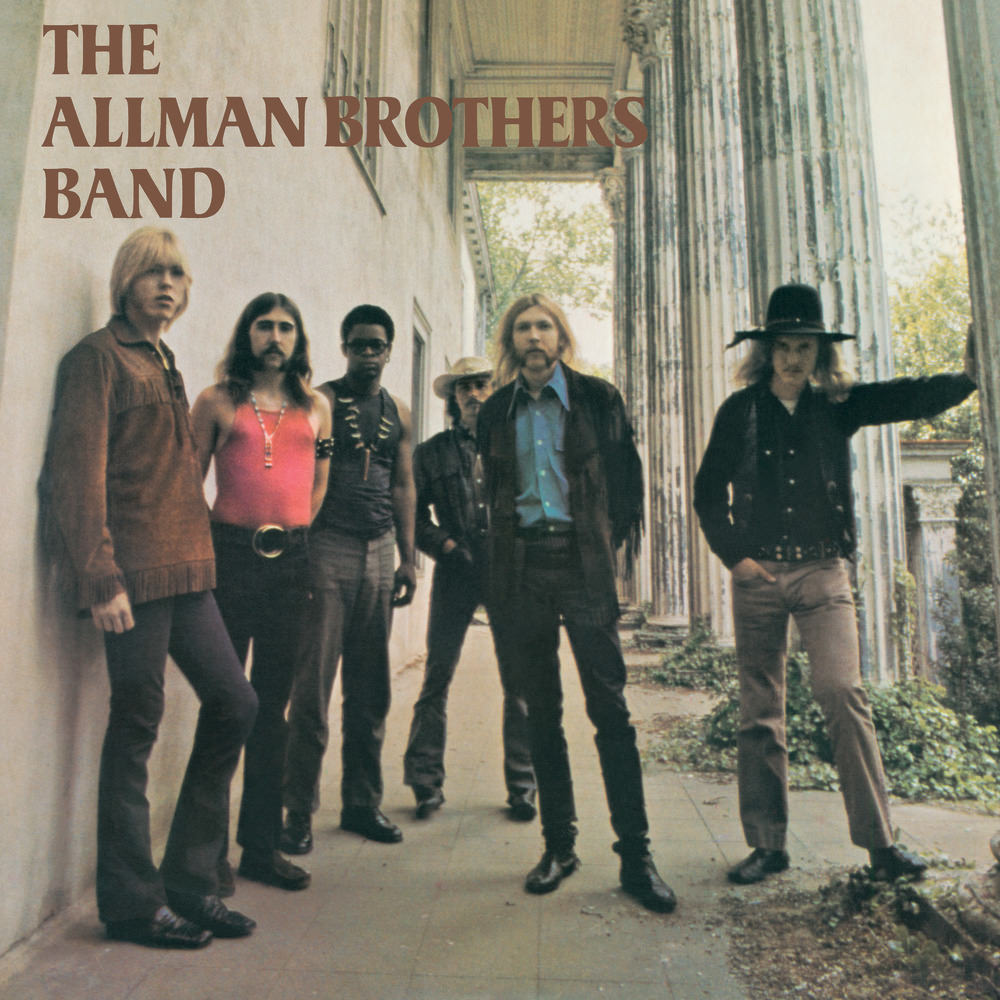

Nearly fifty years ago, six musicians posed on the front porch of a regal but dilapidated antebellum mansion in Macon, Georgia. Vines crept over the porch and paint peeled from the white columns. But the resulting image was a stunner, and those musicians—the Allman Brothers Band—used it as the cover of their 1969 self-titled debut album. Now, thanks to a nearly complete renovation, the Bell House is ready to lay the foundation for a different kind of Southern music.

Photo: Courtesy of Capricorn Records & The Allman Brothers Band Museum

The Allman Brothers Band’s self-titled debut album cover.

Gearing up for its February 20 grand opening, the Bell House will soon be the permanent home of what has been called the “Juilliard of the South,” the Robert McDuffie Center for Strings at Mercer University. Founder and Grammy-nominated violinist Robert McDuffie had long eyed the home and remembering it from his childhood growing up in Macon.

“The minute I saw that house, it’s the one I wanted for the center,” McDuffie says. “Covet is the word that comes to mind. I thought, ‘music needs to be made in that place.”

McDuffie followed the tradition of America’s great conservatories (think the Peabody) that convert grand old homes into musical institutions. And this house has been grand.

Photo: Maryann Bates

The Bell House today.

Originally built in the Victorian style in 1855 by Nathan Beall, the Bell House sits along College Street in College Hill Corridor—a two-square mile area that unites Mercer University’s campus and historic downtown Macon. In 1900, retired Confederate Captain Samuel S. Dunlap added eighteen massive Corinthian-style columns for Greek Revival flair. The house has seen multiple owners since then and was listed on the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places in 1972. For two decades, it operated as Beall’s 1860 (“A famous restaurant where everyone would take their date when they had a little extra change,” McDuffie says) until that spot closed in the 1990s. In 2001, university trustee Gus Bell purchased the home and renovated it for offices, then donated the home to the university in 2008.

Around that time at a university dinner, McDuffie approached Bell about the home to convince him to consider its musical roots. Bell took note. In 2012, the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation chipped in a $1.5 million grant to turn the mansion into the Center’s home and renovations soon began.

Photo: Leah Yetter

Vines creep over the porch before renovation.

The biggest undertaking was converting the second floor to a teaching and practice space with state-of-the-art acoustics. The center limits its enrollment to twenty-six students so the young musicians can have personal access to visiting instructors.

A 60-seat performance hall on the first floor maintains the home’s historic character—leaving original walls intact to create two separate salon rooms.

Photo: Walter Elliott

Salon.

Modern art, like this piece (below) by artist Steve Penley of composer Philip Glass, McDuffie, and conductor Marin Alsop, adorns the space.

“I saw the end game when I was dreaming about it,” McDuffie says. “I always thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to make music in that place? It’s begging for music.’ And now it’s like I’m playing in that dream.”

Photo: Walter Elliott

1 of 3

Photo: Walter Elliott

2 of 3

Photo: Walter Elliott

3 of 3