Home & Garden

Davis Love’s Wild Side

When he needs to get away from golf, Davis Love heads to his 2,890-acre spread on the Georgia coast, which he’s turned into the ultimate sporting retreat

Photo: Squire Fox

On a sunny day in January, Davis Love III sits low in a big leather club chair in the largest of three meticulously restored nineteenth-century cabins at his 2,890-acre hunting retreat, Copeland Hall, on the southern Georgia coast. In the fireplace to his left, oak logs crackle and puff out sweet smoke. He sits with his legs loosely crossed and occasionally rubs his left ankle, the one he’s been rehabbing after surgery. He is freshly showered after the morning hunt — he took two does, trying to keep the herd in check — and has kicked off his boots: His white socks bear the familiar Cabela’s logo.

Love, forty-three, is a fortunate son who has grown up and achieved fame in the white-glove world of professional golf. Now in his twenty-third year as a pro, he has won thirty tournaments, including nineteen PGA Tour events. He’s earned $35,719,267 in official prize money and more than twice that in endorsements. His diverse group of friends includes the elder George Bush, fellow University of North Carolina alum Michael Jordan, and R.E.M. bassist Mike Mills, all avid golfers. He has ridden motorcycles with car-racing greats Richard and Kyle Petty, and hosted Harry Connick, Jr., and his wife, Jill Goodacre, one of the original Victoria’s Secret models.

But Love didn’t build the place as a stomping ground for the rich and famous; likewise, he didn’t claw his way to the top of the golfing world to gain a measure of celebrity himself. In fact, on both counts just the opposite is true: Copeland Hall is mainly a family and turkey-hunting retreat for Love, a place to hide out.

Photo: Squire Fox

“The golf world, it’s so far from reality,” says Love. “Getting back here, riding the tractor around, having a list of chores to do, carrying the firewood, building a fire. This is where I can turn back to more of who I am.”

From where he sits now, Love can look outside and see the nucleus of Copeland Hall: the pond stocked with bass; the bald cypress trees planted at the water’s edge, just fifteen or twenty feet tall now but one day to be towering; the horse barn and fenced-in field where his daughter, Lexie, a sophomore at Alabama University and champion Paso Fino rider, hones her skills; the two other cabins Love had built, one for Lexie and the other for his son, Dru, fourteen. Soon, Dru will roll up the white-gravel drive in a pickup truck driven by one of Love’s buddies, ready for the afternoon hunt.

“This place,” Love says, “it grounds me, gets me back to reality.”

The story of Davis Love III and the creation of Copeland Hall is Southern in many ways. It is Southern because Love is a son of the South who has grown into a Southern gentleman, and the people who helped build the place are also native sons. But the story is also Southern Gothic, because in addition to being charmed, Love’s life has been unpredictably grim and challenging.

Photo: Squire Fox

Davis Love III relaxes in one of the three cabins that dot his 2,890-acre spread in southern Georgia.

Love was born into golf. His father, Davis Love, Jr., was a rare hybrid of expert instructor and accomplished player. But teaching was his passion, which in 1977 led him — and his wife, Penta, and sons Davis and Mark — to St. Simons Island and the top teaching job at Sea Island, the posh golf and hunting resort.

Davis Love III was thirteen at the time, a high school kid who loved golf but who also dabbled in hockey. The move to St. Simons changed that, as the boy found unlimited time to spend with his father on the practice range and the golf course. He told his dad, “Forget hockey, I just want to get good at golf.” And he did.

He attended UNC on a scholarship. In fact, he was so good that he left after his junior year to turn pro. In January 1986, Love placed third in his first professional event and pocketed a $24,100 check. It was enough money, he reasoned, to carry him through his rookie year on the PGA Tour — and to give him and Robin Bankston, his former high school pal and eventual girlfriend, a start as husband and wife.

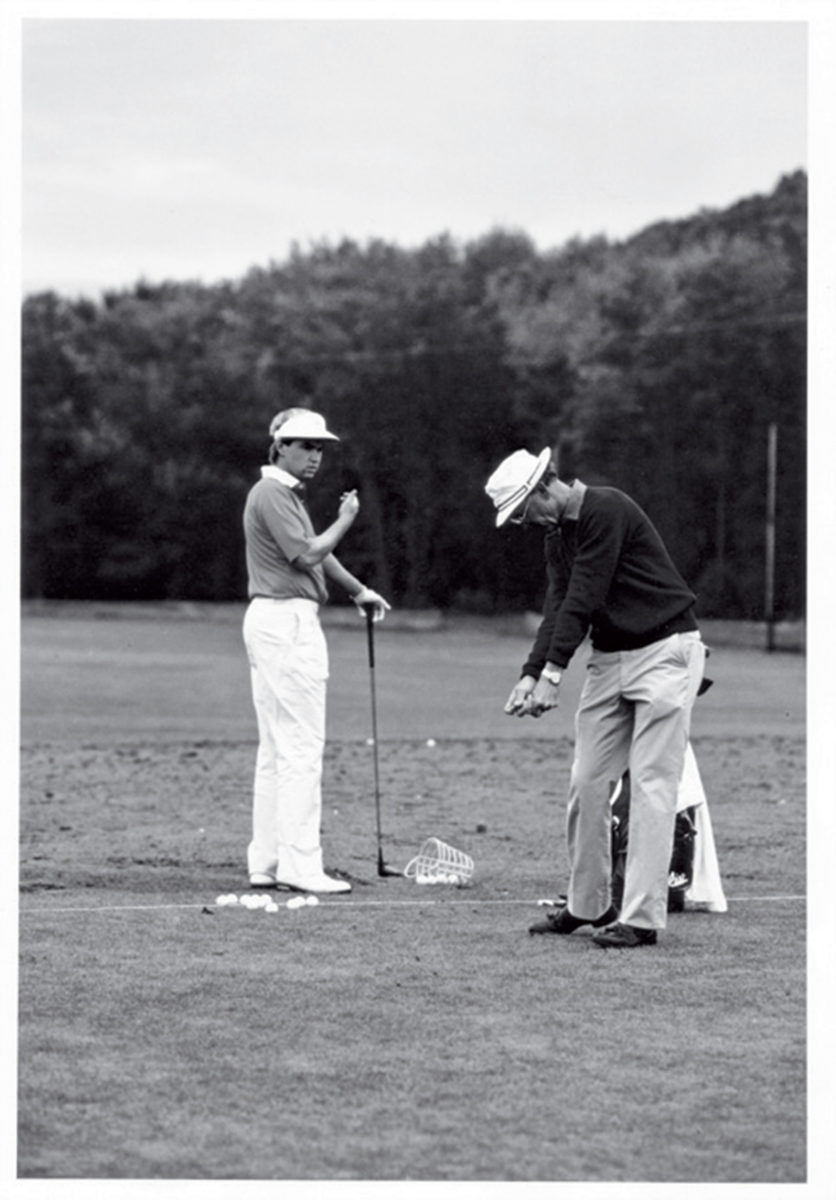

Photo: Squire Fox

Love works on his swing with his father in 1985.

Married on November 22, 1986, Love rode high during the 1987 season, scoring his first victory and $297,378 in winnings. But he faltered in 1988. Lexie, short for Alexia, was born that June, and an already lackluster season went further in the tank for Love, as his thoughts while playing on the Tour inevitably wandered to his wife and child back home in Georgia.

Also hindering Love was his father. The two enjoyed a close relationship, perhaps too close: For more than a decade they had worked together as golf instructor and pupil, logging countless hours on the practice range. In early November 1988, near the start of the fall duck hunting season, Love needed to pick up a new motor for his boat. His dad joined him for the ride. The lonely two-lane road, Route 301, carried the men from St. Simons on the coast to the little town of Waycross and back again. It had been a long time since they’d spent that much time together while not playing golf. Along the way they spoke about parting ways as teacher and pupil.

As Love recalled in his book, Every Shot I Take, when his father left the truck he told his son, “‘Thanks for the good talk. Give a thought to what I said, though. Maybe there’s a teacher out there who can do more for you now than I can.’”

Photo: Squire Fox

The deck of Love's main cabin was built with reclaimed timber.

After the men shook hands, Love’s dad turned to head inside. But before he reached the door, he stopped to wave farewell to his son. It was their last good-bye.

On November 13, 1988, Davis Love, Jr., was aboard a Cherokee Piper, along with the pilot and two other passengers, when it crashed into a forest near the Jacksonville airport. No one survived. When Bill Jones III heard about the plane crash, he cut short a business trip in Atlanta and raced back to St. Simons to see Love. Jones, then thirty-one, was the youngest member of the board of the Sea Island Co. He had arranged a Sea Island sponsorship deal for the younger Love right after he’d turned pro, and the men had become close friends. But now life had taken a tragic turn.

On the porch of Penta Love’s house, Jones spoke to his friend. Love was surprisingly calm. “This is my responsibility now,” Love told Jones. “I’ve got to take care of my mom, my brother. There’s so much to do.”

“He recognized right away what his role was, now that his father was gone,” Jones recalls. “It tells you something about Davis Love, the man.”

Davis Love III, the man, may have been up to the task of handling his father’s death, but Davis Love III, the golfer, was not. For two years, he floundered, routinely being cut from events after just two rounds.

Then, in 1990, he rediscovered his swing, with the help of famed coach Butch Harmon. More important, he rediscovered his love of the game. Over the next decade, Love raked in the kind of dough that only superstar athletes make. The prize money, counted in millions, was nothing compared with the sponsorship deal he got from Titleist — fifty million dollars.

Meanwhile, Love’s family — and responsibilities — grew. In 1993, he and Robin had Dru and acquired the land for a new family home. Love wanted a special place, one that reflected his Southern roots. Through his longtime friend David “D.” Blackshear — a fishing-boat captain who introduced Love to saltwater fishing in the mid-eighties — Love discovered Willis Everett, of Gay, Georgia, whose business was salvaging wood from historic buildings. As the owner of Vintage Lumber Sales, Everett also sometimes saved whole buildings from the wrecking ball, dismantling them, numbering the boards, and storing them in warehouses. Love wanted some heart pine for the floors in his new house, so he arranged to visit Everett at his home.

Photo: Squire Fox

A rare drop-tine mule deer mount that Love bought at auction

Like Love, Everett is a hunter. Not long after Love bought his new land, he and Blackshear made the three-hundred-mile trek from St. Simons up to Everett’s place, south of Atlanta, to do a little hunting and get to know the antique wood expert.

Everett lives in a cluster of reclaimed nineteenth-century buildings that he’s connected with a network of hallways — all antique wood — to form a single residence. Everett says that when he built the first part of his home, about twenty years ago, he was such a purist that he used only hand-forged nails to stitch it together. Everett could tell that Love’s interest in his work was genuine. “He asked a thousand questions,” recalls Everett. “His appreciation for reclaimed wood was clear. Part of it is preserving history — that seemed to be important to him. Green building, as some people call it, also motivated him to some extent. But I think it goes even deeper with Davis.”

That weekend, Love and Blackshear stayed in reclaimed cabins Everett had built on the Flint River, which runs through his property. They were rustic but comfortable, perfect for a hunter. In the end, Love bought the heart pine for the floors in his new home from Everett — but that was just the beginning. “I said to D., ‘We’ve got to get us a couple of cabins like these,’” Love recalls.

Photo: Squire Fox

A stuffed beaver makes little progress on a half-eaten stump.

In the mind of Davis Love III, the seeds of the Copeland Hall compound were planted.

Blackshear tosses another log on the fire, in the big iron pit outside at Copeland Hall, under a canopy of live oak branches. The sun is dropping fast. An eagle swoops below the treetops beyond the bass pond, then rises up and nestles among a thicket of branches. “He’s in for the night,” Blackshear says.

Blackshear knows Copeland Hall, its wildlife, history, and topography, as well as anyone. As part of a 55,000-acre parcel first owned by the Sea Island Co., the estate and the neighboring land served as a hunting and fishing retreat, mainly for wealthy Northerners, in the 1920s, when Sea Island was founded. But during World War II, Sea Island fell on hard times and sold off the land to paper companies, which harvested and replanted countless longleaf pines.

“When Bill Jones III took over as CEO of the company in 1995, he wanted to buy back the land,” Blackshear says. “It was an impossible idea, but Mr. Jones insisted it could work, and he was right. Everyone on the board, including Davis, was given a chance to buy in. So, here we are.”

Photo: Squire Fox

The course at Cabin Bluff has a hybrid layout for casual play and reduced impact on the land.

Love bought three cabins from Everett, and construction began at Copeland Hall in 2002. “The plan was to make one cabin extremely rustic, one in between, and one livable,” Love says. “Well, as we went along, rustic didn’t seem too appealing. My dad was a real traditionalist, so I appreciate the whole historic mentality. But also, I like having the flat-screen TV, the wireless Internet, and all that stuff. You want the modern. The stove we have here looks like early nineteenth century, but it’ll really cook!”

The first cabin completed was originally built between 1860 and 1870, in Sandy Mush, North Carolina. Dru’s Cabin, as it is now known, is a beautiful box of weathered timber with a little front porch for sitting and looking at the bass pond. The other two cabins, even older than Dru’s, also have a rustic feel. In the main cabin, for instance, Love had antique tobacco-drying sticks installed as stair banisters, and the posts holding up the front porch are petrified cat’s-eye pine found on the property: The herringbone markings in the wood are scars from the sap harvest. Love also specified the use of rare antique pecky cypress on some of the interior walls. The wood appears furrowed by insects, but Everett explains that fungus — not bugs — creates the intricate markings. When the trees are harvested and the boards milled, the fungus dies and the imperfect beauty of the lumber comes to life.

Photo: Squire Fox

The dock at Sea Island's Lodge at Cabin Bluff has been the launching point for countless fishing trips off the Georgia coast.

Everett, while still a purist at heart, appreciates what Love has done with the structures at Copeland Hall, including the modern touches, like the glass-walled showers with showerheads the size of dinner plates. “He told me basically what he wanted and turned me loose out there,” Everett says. “He wanted casual family living, that’s what I’d call it, with a historic feel. He has true Appalachian log homes. The construction is a mix of old and new; the daubing between the logs, for instance, doesn’t have horse or pig hair in it — it’s got synthetic fibers. Davis wanted to walk into a cabin that felt like it was from the 1800s, but also had the trappings and the amenities of a current lifestyle. That’s what I gave him.”

Remarkably, all three cabins were finished in a matter of months, by the spring of 2003. As is his practice, Everett had methodically dismantled the structures, numbering each piece of wood like an archaeologist cataloguing dinosaur bones. At Copeland Hall, Savannah gray brick foundations were laid and the buildings quickly took shape. Blackshear worked on the project, as did Love’s brother-in-law, Jeffrey “Big Jeff” Knight, who was married to Robin’s sister, Karen. Big Jeff served as the de facto construction manager; he was also on Love’s payroll as an accountant, keeping track of the golfer’s considerable fortune. Not long after the cabins were constructed, however, Love was blindsided by a visit from Big Jeff.

It was dusk on May 11, 2003, and Love was in the main cabin with Dru. Headlights flashed in the driveway. Love immediately recognized Big Jeff’s truck.

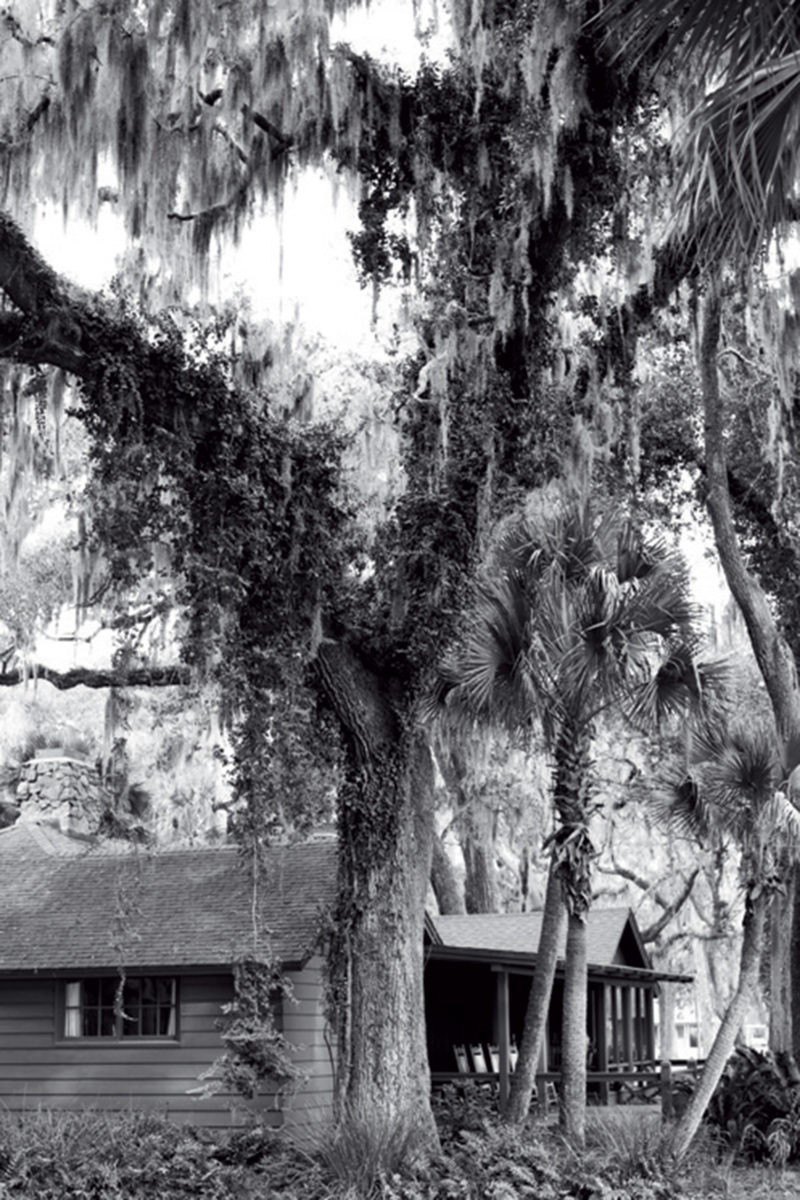

Photo: Squire Fox

Spanish moss hangs low from the live oaks in coastal Georgia

Big Jeff was a frequent visitor and always welcome at Copeland Hall, of course. Love was looking forward to seeing him. But when Big Jeff came through the door, his face was contorted with worry. Love knew in an instant that something was terribly wrong.

Love sent Dru away and sat down at the kitchen table with his brother-in-law. “Look,” Big Jeff said, ashen-faced, “I need to spill my guts here.”

He confessed to stealing nearly one million dollars from Love. The FBI was investigating. When Love recovered from the shock, he swore to stand behind Big Jeff. “I made a promise to do whatever I could do for him and his family, that I would take care of them,” Love recalls. “He was completely baring his soul; he was in trouble — deep. But I talked him through it.”

A few days earlier, Robbie Flanders, a high-school golf teammate of Love’s, had jumped to his death from the St. Simons Island causeway bridge. The suicide was fresh on Love’s mind. “Everyone was on high alert about Jeff,” Love says. “I stressed to my friends and family, ‘We have a very, very serious situation here.’”

Photo: Squire Fox

Two antique guns flank the chimney in the cabin of Love's son, Dru.

Five days later Big Jeff killed himself in his fishing cabin. Love found the body.

The pile of logs in the fireplace is only smoldering now, and Love is getting antsy, glancing over his shoulder frequently, waiting for Dru to arrive. They’ll head out together this afternoon to deer hunt, but both would rather be in the spring turkey woods.

“Turkey hunting is like fly fishing, in that, when you get into it, it’s the only thing you want to do,” Love says. “Don’t get me wrong, I like deer hunting. But turkey hunting is a whole other level. You’re communicating with the animal. You call the animal to you, trying to trick it. It’s fascinating. Dru summed it up one day. He had sat there with his call, making this turkey gobble all day long. We never saw it, not even a glimpse. I said, ‘I’m sorry, buddy.’ And he smiled and said, ‘It’s all worth it.’”

In an antique cabinet upstairs in the main cabin at Copeland Hall, Love has stashed some of his collection of two hundred to three hundred turkey calls. The remainder, the really valuable ones, he has locked away in a safe. “I have some neat stuff,” Love says, “but some of them I didn’t feel right just having around.”

Photo: Squire Fox

Love and Dru take a quick break between hunts.

“I’ve focused it down to collecting calls made by guys I’ve gotten to know,” Love says. “For instance, there’s this preacher from Orangeburg, South Carolina, Zach Farmer. He’s the neatest guy. He comes down here and hunts. And we like him to come because he’s a friend, but he’s a piece of history. He’s seventy years old and has been making calls for almost as long.

“He’s one of the best at what he does,” Love says. “And he appreciates what I do as a professional golfer. But mostly he likes to hunt turkey with me, so he comes up. We’re friends. It’s that simple.”

It’s early February, and Love is talking on his cell phone from California. He played in his first event at Pebble Beach, shooting four under par and finishing tied for twenty-fifth. He was pleased with the performance, his first tournament since he blew out his ankle and had surgery in September. His rigorous rehab put him in excellent physical shape, and he’s confident that despite his age — forty-three-year-olds are like fossils on the PGA Tour — he’s due for a big season.

“I made enough birdies at Pebble to feel good, to feel competitive,” Love says, fresh from the practice round for another tournament, in Los Angeles. “But right now, I’m sitting in traffic in L.A., looking at all the people on Rodeo Drive. And meanwhile, I’m thinking, ‘It would be really nice to be back at Copeland Hall.’”

Photo: Squire Fox

The bell on the main cabin is ready for action.

Love’s voice is suddenly wistful. He says, “Copeland Hall is an important place for me, but it’s not an entirely happy place. When I’m there by myself, I walk in that kitchen and I remember my last conversation with Big Jeff,” Love says. “I remember my promise to do whatever I could do for him and his family, that I would take care of them, and I have.

“I can compare it to when my dad passed away,” Love continues. “For a long time I refused to go to the driving range where I practiced with him. It was just too hard for me. But I got to the point where I was like, I have to go back there, where Dad and I spent hours and hours. I need to go back there and turn this into a positive. I can’t run from it anymore.

“It’s the same for me at Copeland Hall. The place has a whole lot of ghosts. A lot of passion — Willis Everett’s and mine and Big Jeff’s — went into that little circle of buildings. It’s like, everything bad that could possibly happen to you, and everything good, it’s all there, and I love the place.”