Artists

Gregg Allman Says Goodbye

Those closest to him reflect on the making of the late legend’s final album—and on his final days

Photo: Peter Yang

During the last few months of his life, Gregg Allman and his wife, Shannon, would sit together in the sun on the porch of his house outside Savannah, near the swimming pool, with the Georgia Lowcountry landscape unfolding toward the Belfast River. They would hold hands, sometimes in silence. In other moments they would read to each other: He loved Mitch Albom. She turned him on to Maya Angelou. Often they would meditate together, sinking deeply into the moment. One day not long before Allman’s death on May 27 at sixty-nine—after a valiant years-long fight against liver cancer that had spread to one of his lungs—they took a golf cart ride around the neighborhood with their two dogs, Maggie and Otis. The air was warm and still, and Allman understood what was inching closer. “But I don’t feel like this is the end,” he quietly said to Shannon. “I just feel like I’m going somewhere else.”

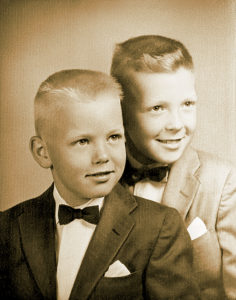

Photo: Courtesy of the Allman Family Archives

A childhood photo of Gregg (left) and Duane.

Gregory LeNoir Allman was always moving, always itching to get back on the road with his band after sometimes just a week of downtime. And, of course, this is the legend who gave us the indelible life mantra “The road goes on forever.” But in 2015, Allman and his manager, Michael Lehman, began discussing a new album, one that Allman could use to meticulously chronicle his life and document the last chapter of his legacy. The just-released Southern Blood is that definitive statement, with Allman and producer Don Was choosing songs that held special meaning. Was selected Bob Dylan’s “Going Going Gone” and the Grateful Dead’s “Black Muddy River,” a song that “just reminded me of him,” Was says, and one that Allman was slow to warm up to but came to love. Allman wanted to do Johnny Jenkins’s “Blind Bats and Swamp Rats” because his brother, Duane Allman, had once played with Jenkins. “Song for Adam” by Jackson Browne was an easy choice, given Allman’s fondness for the tune and nearly fifty-year friendship with the singer, going back to Allman’s time in Los Angeles in the late 1960s. But “My Only True Friend” is Southern Blood’s opener and also its wistful farewell. It’s the one song written by Allman—with assistance from his longtime music director and guitarist, Scott Sharrard—and causes shivers when he sings in his fierce but weakened voice: “I hope you’re haunted by the music of my soul when I’m gone.”

Allman had carefully mapped out the whole arc of Southern Blood, down to its September release date; he didn’t want the album to be lost in the crush of big-name artists who put out albums later in the fall. In addition to handpicking Was—best known for his work with the Rolling Stones—Allman insisted on recording Southern Blood at Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where Duane once pitched a tent in the parking lot because he wanted Fame’s founder, Rick Hall, to give him a job. Duane would go on to contribute searing guitar tracks for Wilson Pickett and Aretha Franklin there, as well as hold rehearsals for what would eventually become the Allman Brothers Band. But the band never made it back to the Shoals. “I never understood why the Brothers didn’t record there,” Gregg told me in 2015.

Photo: Peter Yang

Allman at home in 2011.

But he made up for it with Southern Blood, working from mid-afternoon through the evening in March 2016 at Fame, cutting a couple of tracks each day with his nine-piece touring band playing live. The atmosphere in the studio was thick with history and sentiment. “There was a shadow hanging over the whole thing, but he and I never once spoke about it directly,” Was says. “The songs were puzzle pieces he wanted to put together. We had a lot of fun, a lot of laughs doing the record. The duality is weird. It was such a great time, but yet we knew it would be his last album.” Was had hoped to get Allman to record some additional vocals that would layer harmonies over what was already cut, but Allman’s health started to deteriorate further, and by the end of October 2016, he couldn’t muster the required lung power (with Allman’s blessing, Nashville legend Buddy Miller adds his voice on a number of songs).

With Allman off the road for good, he and Shannon spent several weeks at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, with Allman undergoing treatment to help make him more comfortable. Often, his best friend of forty-eight years, Chank Middleton, would accompany them. It was there in his hospital room that the three of them began to have frank conversations about mortality. “He said, ‘What do you all think about dying?’” Middleton recalls. “And I was like, ‘Oh man, he’s serious and he wants some answers.’ I told him I’m not afraid of death, because he and I got more dead friends than we have alive friends. Duane is over there, B.O. [the Allmans’ original bassist, Berry Oakley, who, like Duane, died as a result of a motorcycle accident] is over there. Otis Redding, Jimi Hendrix. And believe me, they got something going over there. They ain’t just twiddling their thumbs. I was trying to give him something to look forward to.”

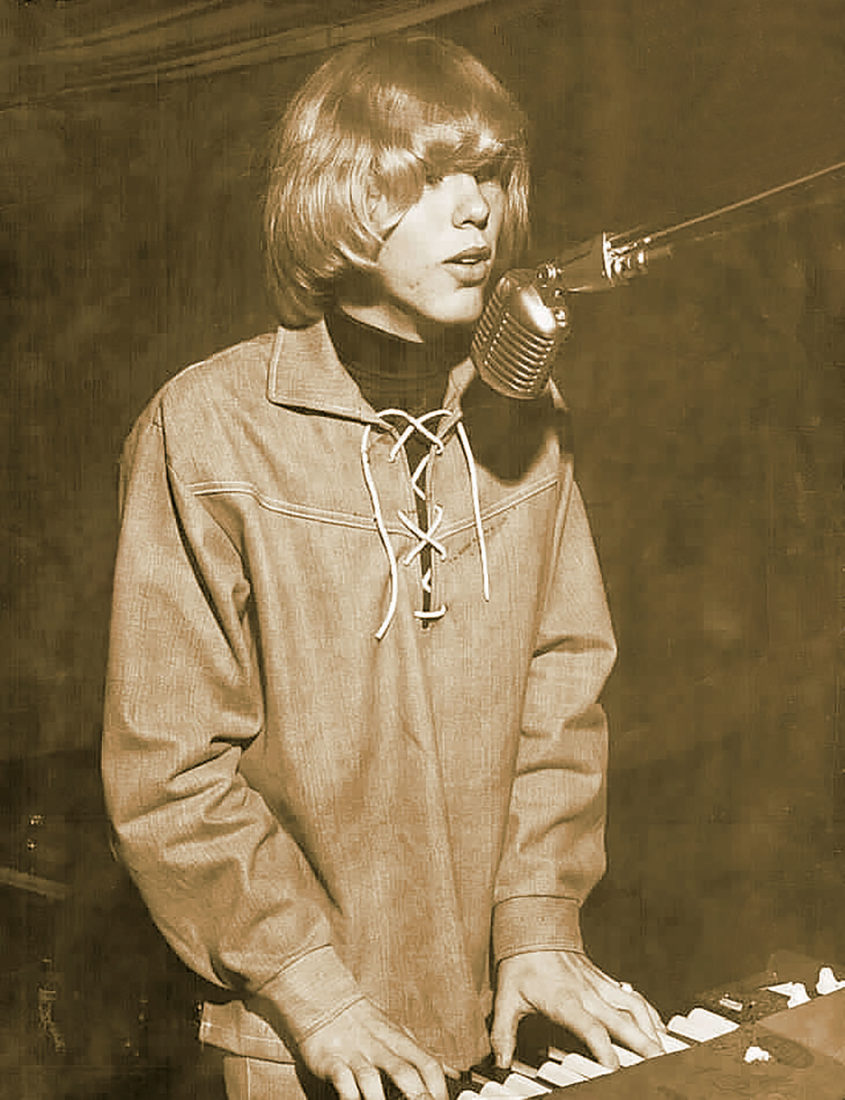

Photo: Courtesy of the Allman Family Archives

Allman performs in 1966 with early band the Allman Joys.

According to Shannon—who met Allman in Jacksonville after one of his solo shows in 2012—Allman never complained about a thing, no matter how awful he felt. She became his sole caregiver for the final year, learning how to cook gluten-free meals and blending him her veggie-loaded green juice. The routine helped, but she was struggling. “I punched a wall, yelled at God, fell to the ground crying,” she says. “A few days before he passed, I threw a pair of shoes across the room. But he got off the couch and comforted me. I asked, ‘How can you love me like this?’ And he said, ‘This is how much I love you. I can’t believe you haven’t run for the hills.’”

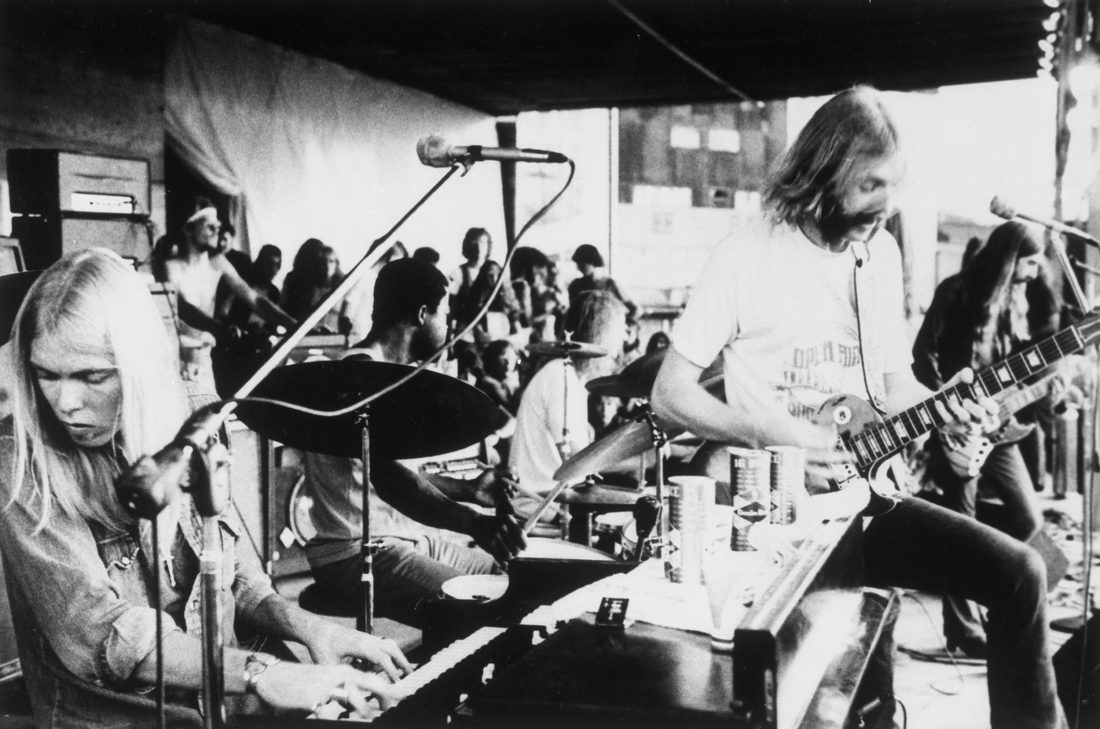

Photo: Jeff Lund

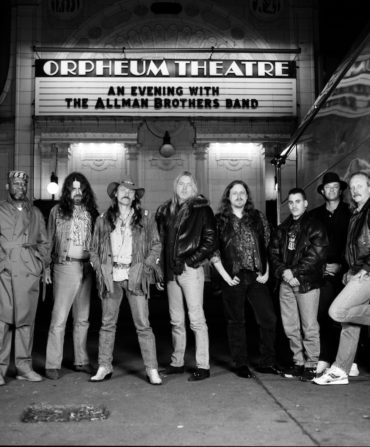

The Allmans onstage in St. Paul in 1971.

The night before Allman died, Shannon called Middleton, who made the two-and-a-half-hour drive from Macon once again. Allman and Shannon curled up on one couch in the house’s cozy den, which is filled with family photos and artwork (Allman loved to paint), while Middleton sat on another couch next to them. They stayed up past 4:00 a.m., reminiscing and listening to Southern Blood’s “Song for Adam” repeatedly so Allman could approve the final mix. “It reminded him so much of Duane,” Middleton says of the song, “and he never stopped mourning his brother.”

As daylight crept into the room, Middleton went upstairs to one of the guest rooms while Shannon and Allman retreated to their bedroom. Allman put on his customary sleeping attire, a fresh white T-shirt, and she surrounded him with pillows. He suddenly sat up for a second, but then lay back down. Sensing that just precious minutes remained, Shannon called for Middleton. She put a flowered shawl over the lamp to lessen the glare and tuned in to the Soothing Jazz playlist on Spotify, music Allman had told her he wanted to listen to as he died. She lay next to him stroking his face and hair, while Middleton held the phone to Allman’s ear so he could hear Lehman telling him that he loved him and assuring him that Southern Blood would be a success, that Shannon and Chank would be taken care of, and that his legacy would be safely guarded. Ten minutes later, Allman reached the final stop on his eternal road.

Photo: Danny Clinch

Allman in the Lowcountry in 2010.

“His spirit went into me, into Chank, his family, and to anyone who played or loved his music,” Shannon says, fighting back tears. “He always made it look so easy when he walked out onstage. But he fought so hard, and he put that energy into living a full life until the end. And when he passed, he looked just like an angel.”