For the last century, the Grand Ole Opry has shaped music and entertainment far beyond its Tennessee home. “Anybody that loves and finds their way into country music knows about the Opry,” explains Vince Gill, the legendary musician who was inducted as a member into the Nashville institution in 1991. “It started before any of the records were ever made, and it represents the entirety of country music in such a beautiful way.”

Indeed, the weekly variety show helped define the genre when it premiered in 1925, then spent the next one hundred years playing host to its most iconic stars and delivering once-in-a-generation collaborations, thrilling musical surprises, and unforgettable backstage stories. It also continued to reach new audiences, weathering (and in some cases leading) multiple media revolutions while bridging generational, geographical, and geopolitical divides. Countless Opry moments—songs, inductions, ovations, and behind-the-scenes conversations—could be considered landmarks. But here, rather than rehash the best-known stories or try to settle on the most legendary performances (an impossible task, really), we’ve traveled back in time for a dozen-plus Opry milestones that say something deeper about country music’s biggest stage.

“The Opry represents the history of this music more so than the hit records,” Gill says. “The one thing that stays consistent for country music, regardless of the styles or how it’s changed, is that the audience never gets tired of a great singer singing a great song.”

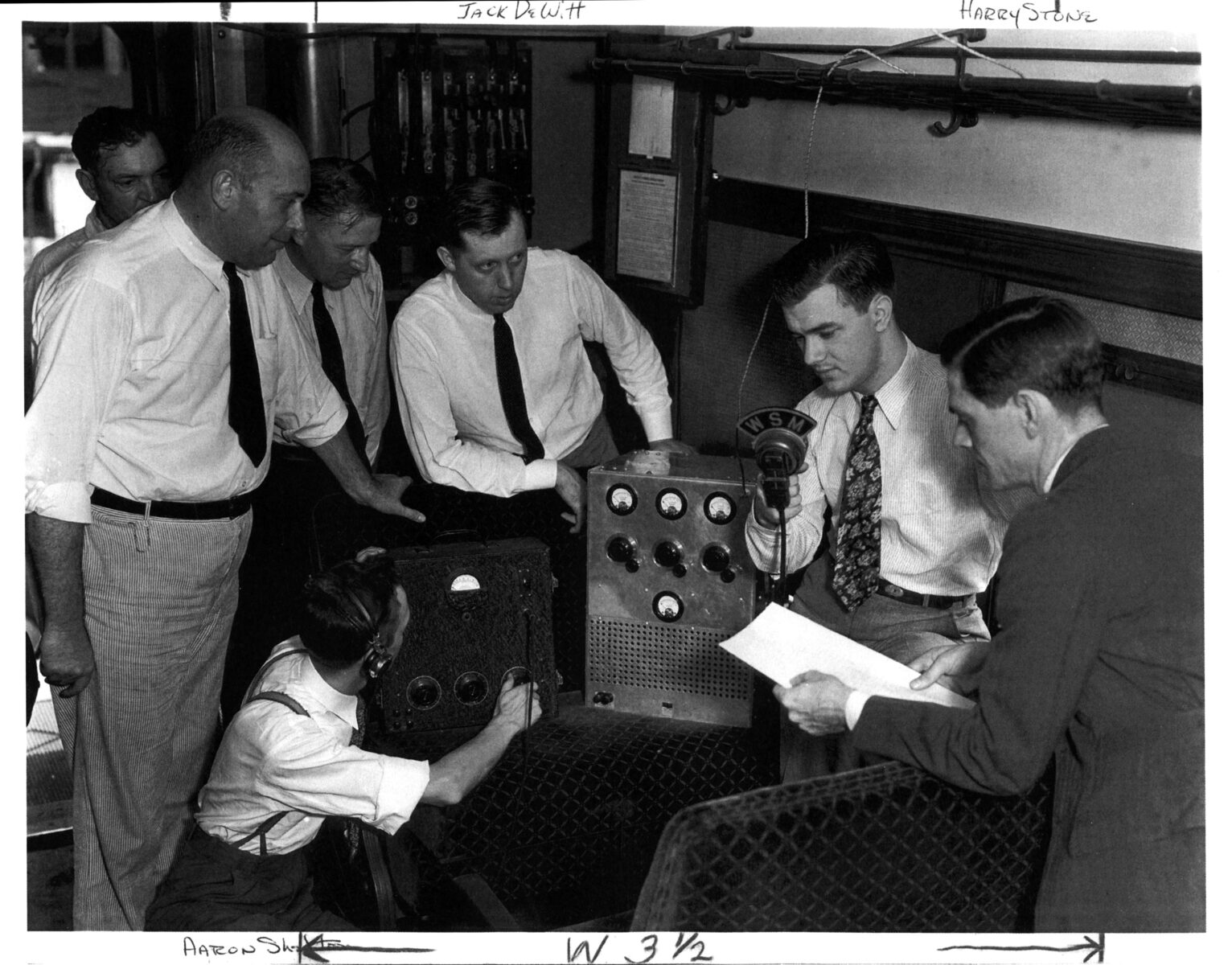

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

The WSM Barn Dance team broadcasts in Nashville using their first remote pickup transmitter.

1925: An insurance company launches...a radio station?

“Some people’s misconception is that because the Opry is Southern, it’s kind of backwater. But it was the most technologically advanced company in the nation.”—Tim Davis, head archivist for the Grand Ole Opry

It’s not a stretch to say that WSM Barn Dance—the radio program that would become the Opry—began as somewhat of a content marketing scheme. “This was an insurance company that decided to build a radio station in 1925, and they had money to throw to make a very nice fancy radio station,” says Tim Davis, head archivist at the Grand Ole Opry. WSM, the station’s call letters, stood for “We Shield Millions,” the motto for National Life and Accident Insurance Company. “They had a genius engineer, Jack DeWitt—he’d built the first radio station in Nashville when he was a teenager—who shepherded technological advances for years.” In 1932, DeWitt was involved in creating an 878-foot, 50,000-watt tower—the tallest in the nation at the time—that brought the Opry to listeners across the nation. And in 1941, he was there when the station got the country’s first ever commercial FM license. “The coolest thing to me about the Opry is how advanced it was from day one,” Davis says. “This was a very powerful technological company—they just happened to have this hillbilly show.”

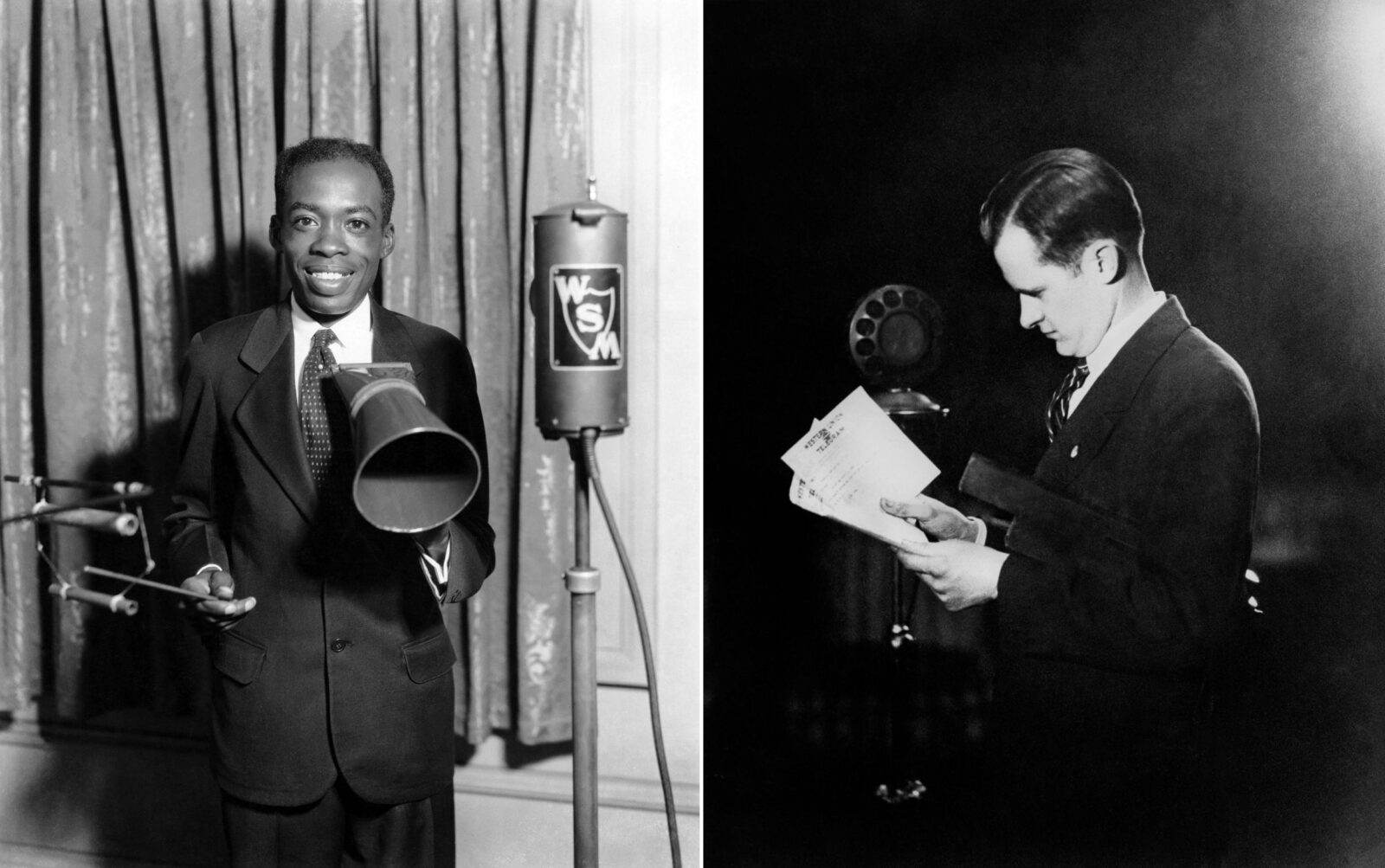

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

Opry musician DeFord Bailey; George D. Hay, founder of the Grand Ole Opry.

1927: DeFord Bailey’s train whistle inspires a name

“For the past hour, we have been listening to music taken largely from grand opera, but from now on, we will present the Grand Ole Opry.”—George D. Hay, founder of the Grand Ole Opry

What’s the difference between folk music and country music? To hear Davis tell it, the answer lies in the theater of it all—and the Opry had a hand in making the distinction. “George D. Hay saw himself as a showman,” Davis says of the Opry’s founder and first host. “He created this radio program to include a little bit of circus magic to it. It was more than just trying to show people what authentic music sounded like; there was some fun in there, too.” Hay also had a knack for leaning into the music audiences wanted to hear.

One of the most popular performers was DeFord Bailey, a “harmonica wizard” who’d learned to play while bedridden with polio during his childhood. The Opry’s first Black cast member (before the induction of permanent members became the norm), Bailey was known for his uncanny ability to imitate various sounds with his instrument. When he debuted the song that would become his trademark in December 1927—“Pan American Blues,” which featured a spot-on train whistle harmonica bit—the program then known as WSM Barn Dance directly followed a classical music show. Hay got a kick out of the juxtaposition. “For the past hour, we have been listening to music taken largely from grand opera,” he said as he introduced Bailey, “but from now on, we will present the Grand Ole Opry.”

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

The Grand Ole Opry settled at the Ryman Auditorium in 1943.

1934–1943: The Opry makes a home at the Mother Church

“We used to joke that there were two kinds of fans: the fans that came to see the show, and the little funeral home paper fans that they would hand out at the door.”—Bill Anderson, the Opry’s longest-serving member

After its early years at the WSM studio, the Opry moved venues several times, to Hillsboro Theatre in 1934, to Dixie Tabernacle in 1936, and then to War Memorial Auditorium in 1939. Eventually, in 1943, the show made a home at the Ryman Auditorium, a former church right off Lower Broadway in downtown Nashville. But it wasn’t exactly the Mother Church that concertgoers know today. “Back in the day, before it was air-conditioned, the Ryman in the summer was the hottest place in the world,” says Bill Anderson, the soft-singing crooner who holds the title of the Opry’s longest-serving member (he was inducted in 1961).

Audiences and performers alike seemed to embrace it—with a few jokes along the way. “They’d leave the windows open, and I was in the middle of a song one night when a bug flew right down my throat,” Anderson recalls. “I’m coughing, trying to recover, when one of the musicians standing close to me just leaned over and whispered, ‘Let the bug sing!’”

Eventually the program outgrew the old building. In 1974, the Grand Ole Opry moved into its current confines at the Grand Ole Opry House just east of town, bringing with it a six-foot wooden circle from the original Ryman stage and embedding it into the new stage’s floor as a tribute to its former home.

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

Minnie Pearl in the 1940s.

1940: Minnie Pearl says “How-dee!” to the Opry

“She was the one that ingratiated people to the Opry stage. They loved her and her character and her spirit.”—Kelly Sutton, the Opry’s first full-time woman announcer

“For years, the matriarch of the Grand Ole Opry was Minnie Pearl,” says Kelly Sutton, the Opry’s first full-time woman announcer, who joined the program in 2022. Comedy had always been a part of the Opry, even before the induction of full-time stand-up comedians like Jerry Clower in 1973 or Henry Cho and Gary Mule Deer in 2023. “That was part of a lot of musician’s repertoire, doing comedy,” Davis says of the Opry’s early days. But Sarah Colley Cannon, the trained actor and former debutante who played Minnie Pearl, a self-deprecating character who poked polite fun at small-town life, had a special connection with audiences. She’d grown up just fifty miles southwest of Nashville, and sweetly satirized the mannerisms, speech, and warmth she saw across the country, particularly in rural areas. “People saw themselves in her. They felt like they knew her immediately,” Sutton says. And when her good-natured hillbilly satire began to regularly appear alongside the musical and presenting skills of Roy Acuff, audiences really went wild. “She was a queen of comedy,” recalls Linda Brady Tankersley, the Opry’s longest-tenured usher. “She and Roy Acuff were just a treasure to see on that stage.”

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

Patsy Cline on the Opry stage in 1962.

1960: Patsy Cline gains entry simply by asking

“We have no idea how the decision is made. It’s a mystery. But what I do know is that once it is, my only job is to say, ‘Welcome. I’m so happy you’re here.’”—Ashley McBryde, singer-songwriter and Opry member

It’s hard to get a straight answer about how artists gain membership to the Grand Ole Opry. “I have literally no idea,” says Chris Janson, who was inducted in 2018. Sure, it seems to involve some combination of country music bona fides, previous Opry appearances, and a little magic timing, but one thing is abundantly clear: You have to be invited. “I was watching a baseball game on television, and I almost didn’t answer the phone,” says Bill Anderson about his own invite. “The Opry manager just said, ‘How would you like to become a member of the Opry cast?’ And I mean, that was like asking me if I wanted to go to heaven when I died.”

In 1960, Patsy Cline made history by becoming the first and only Opry member to gain induction simply by asking for it. She’d played the Opry stage for the first time in 1955, appearing alongside Little Jimmy Dickens and Ernest Tubb to promote her first single, “A Church, a Courtroom and Then Goodbye.” When she eventually asked Opry manager Ott Devine for a membership, he gladly obliged. “Patsy, if that’s all you want,” he said, “you are on the Opry.” From there, she was a regular fixture on the show until her untimely death in 1963, lending glamour and a pop-informed sound that would lay the groundwork for fellow greats like Dolly Parton and Tammy Wynette.

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

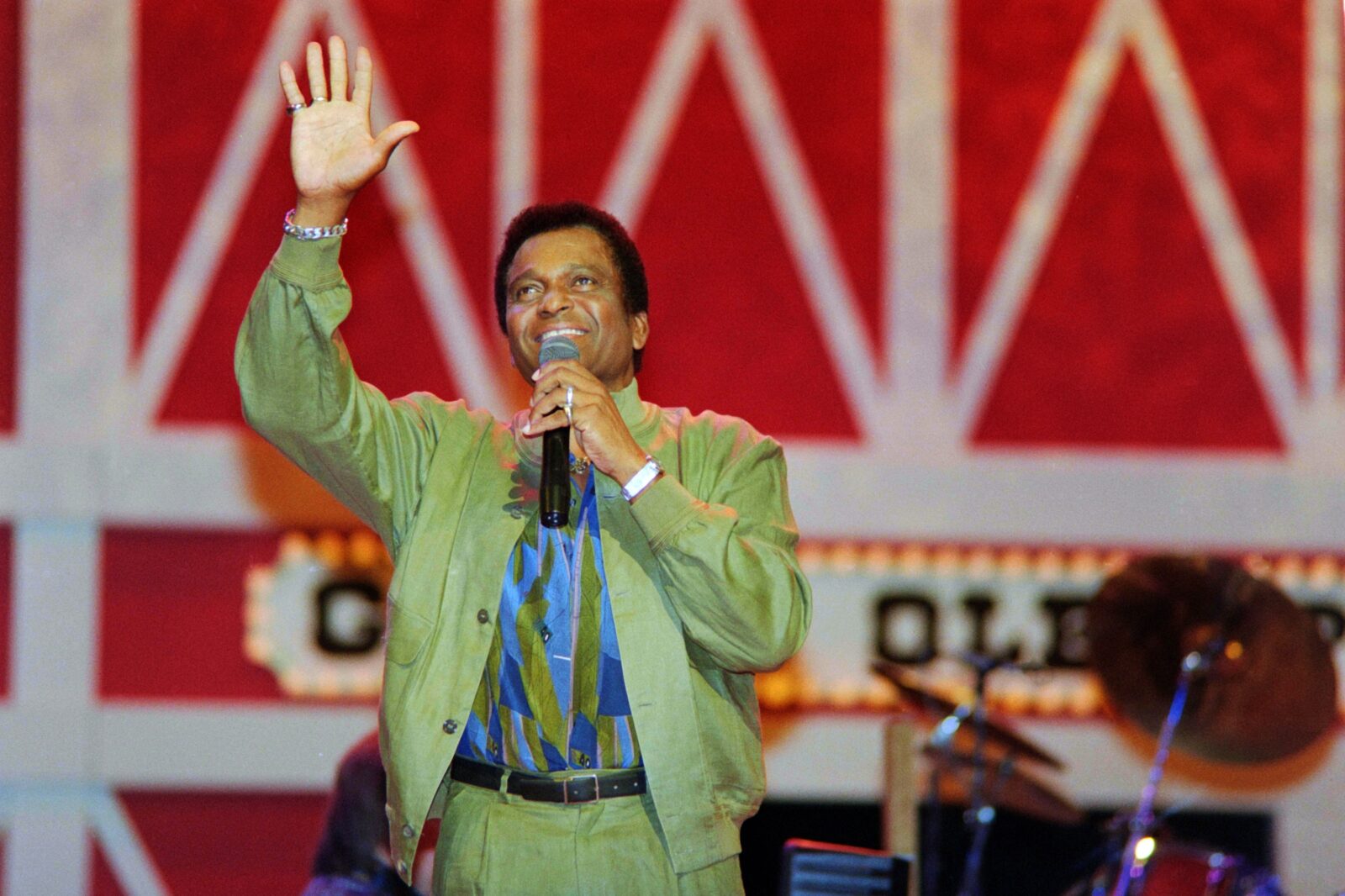

Charley Pride performs at his induction to the Opry in 1993.

1967: Charley Pride debuts on the Opry stage

“I think Charley Pride changed everything for everyone.”—Tim Davis

The Opry, like much of the wider country music industry, has rightly received criticism over the years for its lack of inclusion. Harmonica wiz DeFord Bailey was fired as a cast member in 1941 over a publishing contract dispute—something Davis contends probably wouldn’t have happened to a white performer of his stature. Charley Pride debuted in 1967, the same year his first hit single, “Just Between You and Me,” took off on the charts. He was the first Black solo singer on the Opry stage and would become the first officially inducted Black Opry member, though not until 1993. (He was the only Black artist to be inducted as a permanent member until Darius Rucker gained entry in 2012.) Linda Martell, the artist behind such classics as “Color Him Father” and the first Black woman to play the Opry, garnered two standing ovations at her debut in 1969, but she only played the circle a dozen times, never gaining entry as a member and ultimately speaking out about how the larger country music industry pushed her out.

The twenty-six-year gap between Pride’s debut and his induction speaks to another aspect of the Opry’s history: Some of the most popular artists of the twentieth century turned down membership due to the then-strict appearance requirements. “When I first came to Nashville, the commitment at the Opry was pretty much written in stone,” says Anderson, who was inducted in 1961. “If you were an Opry member, you had to be there half the weeks of the year, performing.”

For Pride, an artist on the cusp of enormous commercial success in the late sixties, the Opry wasn’t the right career move. “I had a standing invitation to join the Opry since 1967, but they had a requirement that you had to play twenty-six Saturdays per year,” Pride said. “Those were the best days where you could draw and make your money out on the road.” He’s not the only one to decline membership or wait decades for his due. George Strait, for example, couldn’t commit to so many Nashville appearances and still maintain his Texas residence; the “King of Country” is still not a member. And Gene Watson, the artist behind hits like “Love in the Hot Afternoon” and “Farewell Party,” debuted in 1972 and wasn’t inducted until 2020.

“They asked me when I was early on [to join the Opry],” Watson says. “And I was so hot on the radio and everything that I couldn’t abide by the rules.” He still played the circle when he could, and the long wait for official membership didn’t make the honor any less special when his time finally came. “To this day, the Grand Ole Opry is the top of the heap. That’s the pinnacle. If you’re in the country music business, it don’t get no higher point than that.”

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

Linda Brady Tankersley; Diana McBride, known to everyone around the Opry as "Lemonade."

1974: The Opry’s longest-serving usher works her first show

“Every member of the staff is just as sacred as every member of the band.”—Ashley McBryde

Linda Brady Tankersley moved to Nashville in 1963 for a job with National Life and Accident Insurance Company. She stayed for forty years, but it wasn’t her most tenured role: In 1974, she got a side gig as an usher at the Grand Ole Opry, and she’s still working shows today. “We raised families, worked other full-time jobs, and still kept our Opry jobs too,” Tankersley says, stressing that she’s not the only usher to serve a half century at the institution. “It’s just too much fun to give up.”

Fans may only see the on-stage sparks, but every cog in the Opry machine is a cherished part of the tradition. “It really is a family,” Anderson explains. “I tell people sometimes that the best show is backstage. It’s that home we can all come back to, no matter where we wander off.” McBryde is especially effusive about these behind-the-scenes Opry heroes—especially Diana McBride, who everyone affectionately refers to as “Lemonade,” a longtime staffer who stocks food and drinks in the dressing rooms. (“She’s five foot and made of pure light and joy,” McBryde says.) And apparently, when Post Malone made his debut earlier this year, he stuck around after nearly everyone else had left, unpacking the night’s events with the security guard outside.

“When they leave the Opry at night, the fans’ll look at me and say, ‘You have got the best job in the whole world,’” Tankersley says. “And I say right back, ‘I sure do.’”

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

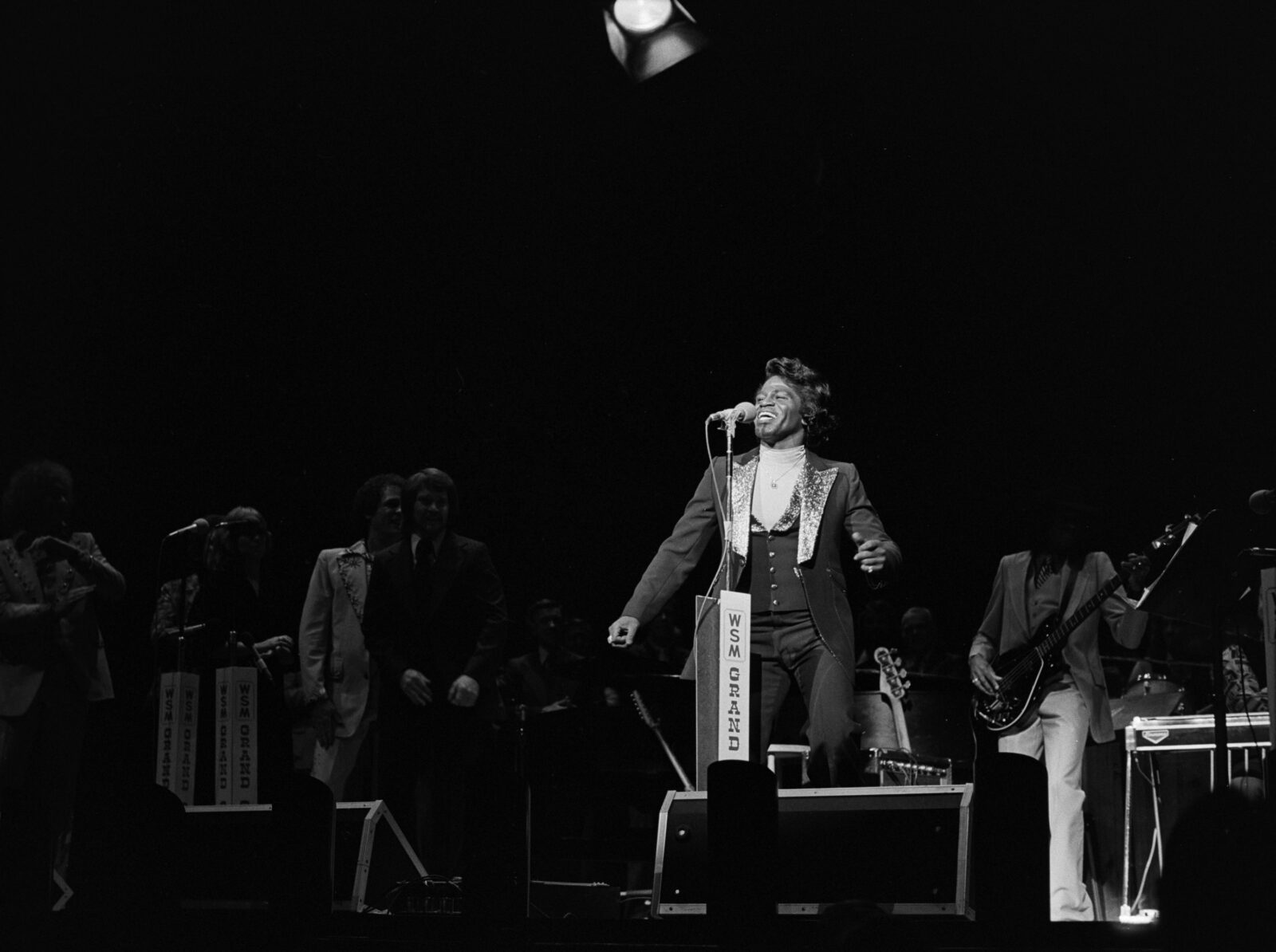

James Brown at the Opry in 1979.

1979: James Brown lights up the stage—and the Opry lights into naysayers

“They treated me like I was a prodigal son.” —James Brown

The Opry has long garnered a host of opinions about what—and who—does and doesn’t belong. Despite the fact that WSM Barn Dance began as a variety show—and country music itself began as a derivative of folk, gospel, blues, and other sounds—there’s a long history of fans, critics, and even members complaining about who graces the legendary circle.

“The big controversial one was James Brown—and I think he’s maybe the most talented person to ever be on the Opry stage,” Davis says. The then-forty-five-year-old soul singer from South Carolina, who was invited to the stage by Porter Wagoner, played “Get Up Off That Thing” as well as a medley of “Cold Sweat,” “Can’t Stand It,” and “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag.” But Brown knew his audience (he spoke later in life of his love for Opry stars like Little Jimmy Dickens and Minnie Pearl), so he also threw in the country classics “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Tennessee Waltz,” and “Georgia (On My Mind).” That didn’t stop the angry letters from pouring in.

“I’ve read some of those letters; people complaining for not just genre, but race,” Davis says, noting that the Opry didn’t bend to the criticism. “The executive response was that the Opry has always been a variety show and this is our guest. We have a variety of music on—we’ve been doing that for years and we’ll continue to do it.”

Many of the Opry’s most beloved voices stand firm by that philosophy. “The Opry has done a good job of reminding us that in country music, the people we write about and the people we sing about are the kind of people that build a bigger table,” McBryde says. “If we are who we sing we are, then anyone who says, This is what country is to me, and I’m going to perform it here because you say I get to, is absolutely welcome.”

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

Jeannie Seely performs at the Opry in 1974.

1985: Jeannie Seely becomes the first woman to host her own Opry segment

“She knew that when she was pushing back, she wasn’t doing it just for herself; she was doing it for everyone that was going to come after her.”—Kelly Sutton

Jeannie Seely’s 1966 Opry debut garnered applause and adoration, but her wardrobe for the big moment also ruffled a few feathers—including, apparently, those of Opry mainstay Roy Acuff.

“He didn’t necessarily love the length of Jeannie’s skirts, and I guess he made mention of that,” Sutton says. “Jeannie said, ‘I’ll stop wearing miniskirts when the people that come through the doors do.’” She won that battle—and many others—and remained a member for fifty-seven years until her death earlier this year. In 1985, Seely even became the first woman to host a segment, an honor that didn’t come easily. “She approached the general manager at the time and said, ‘Hey, why can’t I host my own segment?’ And his response was, ‘Well, Jeannie, it’s just tradition,’” Sutton says. “Apparently she said, ‘Oh, it’s tradition! So it just smells like discrimination.’”

Seely wasn’t the only woman to push back against the Opry’s boundaries. Rose Maddox, the fiddle player and lead singer of the Maddox Brothers and Rose, lasted only a year on the show in the 1950s after performing in costumes that revealed her shoulders. And in 1975, the program nearly barred Loretta Lynn from performing her controversial single “The Pill;” it took a closed-door meeting to ultimately clear the song for Opry ears.

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

Jeannie Seely was the first woman to wear a miniskirt on the Opry stage.

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

Vince Gill and Roy Acuff at Gill’s induction into the Opry in 1991.

1989: Vince Gill embodies the Opry’s spirit—by declining his first invitation

“They will treat you as their own flesh and blood just based on ‘Opry,’ that single word.”—Ashley McBryde

For a young Vince Gill, playing the Opry was a lifelong dream. “The thought of Nashville, Tennessee, was always centered around the Opry,” he recalls. A widely respected sideman in Music City even before he became a renowned songwriter and solo artist, Gill actually declined multiple opportunities to play the Opry stage in other artists’ bands. “It meant enough to me that the first time I ever got the opportunity to play there, I wanted it to be for me.”

Yet when he finally got his first solo invitation, he turned it down. “I had promised my daughter I would play with her at the [elementary school] talent show,” he says. They sang “You Are My Sunshine.” Gill, of course, would eventually have his debut, but in some ways, his original choice to favor family was about as Opry as it gets.

“It’s for families,” Davis says of the Opry’s founding mission. In fact, plenty of members were introduced to the Opry by their families in the first place. “The first time I came to the Opry, my mother and dad brought me,” Anderson says. “And when my granddaughter turned sixteen, she got a job as the youngest usher they’ve ever hired. She works there every week and just absolutely loves it. To know that somebody kin to me is hopefully going to carry on the love for it that I have? It’s amazing.”

As for Gill’s daughter, she was able to graduate from the talent show to the Opry House, too. “I brought her to the Opry as I got to play more and more, and she sang with me,” Gill says. “And just a couple months ago, her daughter Everly came out and sang a song with me at the Opry. All the generations of my life know how dear it is to me out there.”

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

Johnny Paycheck, shown here with Bob Whittaker (left) and Steve Wariner, is invited to join the Opry.

1997: Johnny Paycheck’s on-stage surprise inspires a tradition

“Today, when they induct somebody, it’s almost like a coronation.”—Bill Anderson

Johnny Paycheck was already a household name when, in 1997, Opry president and general manager Bob Whittaker caught him off guard during a performance with an invitation to join the organization. Unwittingly, he helped usher in a new Opry tradition: on-stage or on-air surprise invitations.

“I was invited to be an Opry member by one of my brothers in the music business, Keith Urban, and he surprised me totally,” recalls Chris Janson, whose 2018 invitation came during a Ryman headlining show. Gene Watson was similarly shocked when Gill re-invited him to join in 2020 (decades after he’d turned down the first invitation). “That’s the most surprised I’ve ever been in my life in the music business,” Watson says. Delivering the happy news is definitely a perk of the job for Gill: “I got Steve Earle not too long ago, and the look on his face? I’ll never forget it as long as I live.”

While this type of induction is relatively new, surprises in general have always been a part of the Opry magic. Reba McEntire often tells the story of her Opry debut being cut short by Dolly Parton, who’d shown up last minute, ready to play. (The two are now close friends.) Merle Haggard delighted the audience with an unannounced set just a few months before his 2016 death. (“The audience cried and gave him a standing ovation,” Tankersley remembers.) And more than one Opry insider recalled Alan Jackson phoning from the tarmac just before midnight one Saturday hoping management might keep the show going long enough for him to make it to the Opry House.

“One of the greatest parts of my job is that split second when you know that 4,400 people from around the world are about to be so thankful they chose that particular night to come to the Grand Ole Opry,” says Opry senior vice president and executive producer Dan Rogers, recalling one night when Garth Brooks shocked the audience with an appearance. “When the band kicks into ‘Callin’ Baton Rouge’ and he walks out—we’re all looking at each other, thinking ‘How did we get so lucky?’”

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

The flooded stage in 2010.

2010: After a massive flood, the show goes on

“The Opry never missed a show…We called it our High Water Tour.”—Linda Brady Tankersley, longtime Opry usher

In May 2010, record-breaking rainfall in Middle Tennessee led to historic flooding, killing dozens and causing billions of dollars in damage. The Opry House was submerged. Artifacts were destroyed—the staff archivist at the time took a rowboat to salvage what she could—and the show was left without a venue.

The team immediately sprang into action, arranging to move shows all around town. Ushers were offered leave, but many didn’t take it; they wanted to help. “We went everywhere,” Tankersley says. “We went to the War Memorial Building, which was the home of the Grand Ole Opry before it moved to the Ryman. We went back to the Municipal Auditorium, the Baptist church across from where the Opry is now, Lipscomb University. Everybody just worked together and made it happen. The Opry never missed a show.”

After extensive renovations and repairs, the Opry House reopened on September 28, less than five months after the flood. “Just about every Opry member was on stage and performed,” Tankersley said. “It was a fantastic show.”

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

Ashley McBryde at her induction into the Opry with Terri Clark in 2022.

2017: Ashley McBryde writes her Opry debut into existence

“For them to say, ‘This is what we call an Opry moment’—that I got to have one of those, and it was mine and it was yours and it was ours—was just magic.”—Ashley McBryde

If you’re curious about what playing the Opry continues to mean to aspiring songwriters and performers, Ashley McBryde’s 2017 debut—and the song that foretold it—is a good place to start.

“On the day Guy Clark, one of my hero songwriters, passed away, my co-writer said, ‘Have you played the Opry yet?’ And I said, ‘No, I haven’t, but I will,’” she recalls. “I was trying so hard to keep my head up, to know that eventually it would happen. Our goal that day was to write the song I would sing if I ever got to play the Opry.” That song: “Girl Goin’ Nowhere,” which rehashes all the times its narrator was told not to waste her time with music before building to a chorus celebrating sellout crowds and the joys of on-stage life.

Two years later, the milestone that inspired the lyrics came true. “The day of my debut, we did my makeup five times. I couldn’t stop crying,” McBryde says. “To sing ‘Girl Goin’ Nowhere’ on that stage, knowing that was the reason it was written, and now I’ve done it? All standing ovations are heart squeezing, but to have a standing ovation at the Grand Ole Opry was just otherworldly. Calling it Mount Rushmore doesn’t quite do it; calling it country music’s Hollywood doesn’t, either. The Opry is special because we were taught that it was, and we treat it that way.”

Photo: courtesy of Ryman Hospitality Properties

From left: Yolanda Adams, the War and Treaty, Amy Grant, and Steven Curtis Chapman perform a gospel medley including “How Great Thou Art” at Opry 100: A Live Celebration in 2025.

2025: Artists across generations celebrate one hundred years

“The Opry is a living, breathing community. It is always evolving—looking toward the future, but respectful of its past.”—Dan Rogers, the Grand Ole Opry’s senior vice president and executive producer

The Grand Ole Opry will celebrate its first century with an official birthday show on November 28. But additional events throughout the year have already honored such legends as Porter Wagoner, Bill Monroe, and Minnie Pearl, with lineups full of big names, up-and-comers, and surprise pop-ins: Shows so far have included country and bluegrass mainstays like Old Crow Medicine Show, Ricky Skaggs, Emmylou Harris, and Mickey Guyton, but also folks like comedian Leanne Morgan and even Ringo Starr.

“Opry audiences know they’re going to hear artists from the past along with superstars of today,” says Dan Rogers, the Opry’s senior vice president and executive producer. “But they’re also very likely to hear someone who is just beginning to make their name in country music—a superstar of the future.”

The future of this Southern institution, too, looks plenty bright. “I think the entirety of [the Opry] is what makes it so special—the fact that through it all, it’s lasted,” Gill says. “With all the technology, all the changes—AM radio to FM radio; FM radio to satellite radio; satellite radios to digital media to the internet to the blah, blah, blah—that little radio show is still hanging in there a hundred years later.”