Nancy Plemmons pulls a bag out of the freezer. “This sochan might look bad now, but it’s delicious,” she chirps.

Plemmons is a full-blooded member of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, living on tribal land outside Murphy, North Carolina. She gathered these wild greens in her front yard months ago. Before they soften in the pork fat pooling in her skillet, they’re a frosty mass the emerald color of first growth. “This is a spring tonic, and everybody eats it. Everybody! Even Bill.”

Bill Thomas smiles, shifting in his creased khakis. He and Plemmons met years ago, when Thomas was the lab director for a few hospitals in the area. Plemmons ran an indigenous art gallery with her late husband, Tony, and eventually opened up to the soft-spoken but persistent pathologist about the likes of bean bread, black walnut porridge, and those sochan greens. “After a while, she agreed to fix me a plate of food,” he says. Later, she introduced him to friends who foraged for mushrooms and medicinal herbs. “That’s when I started to think that it would be neat to put together a cookbook,” he says.

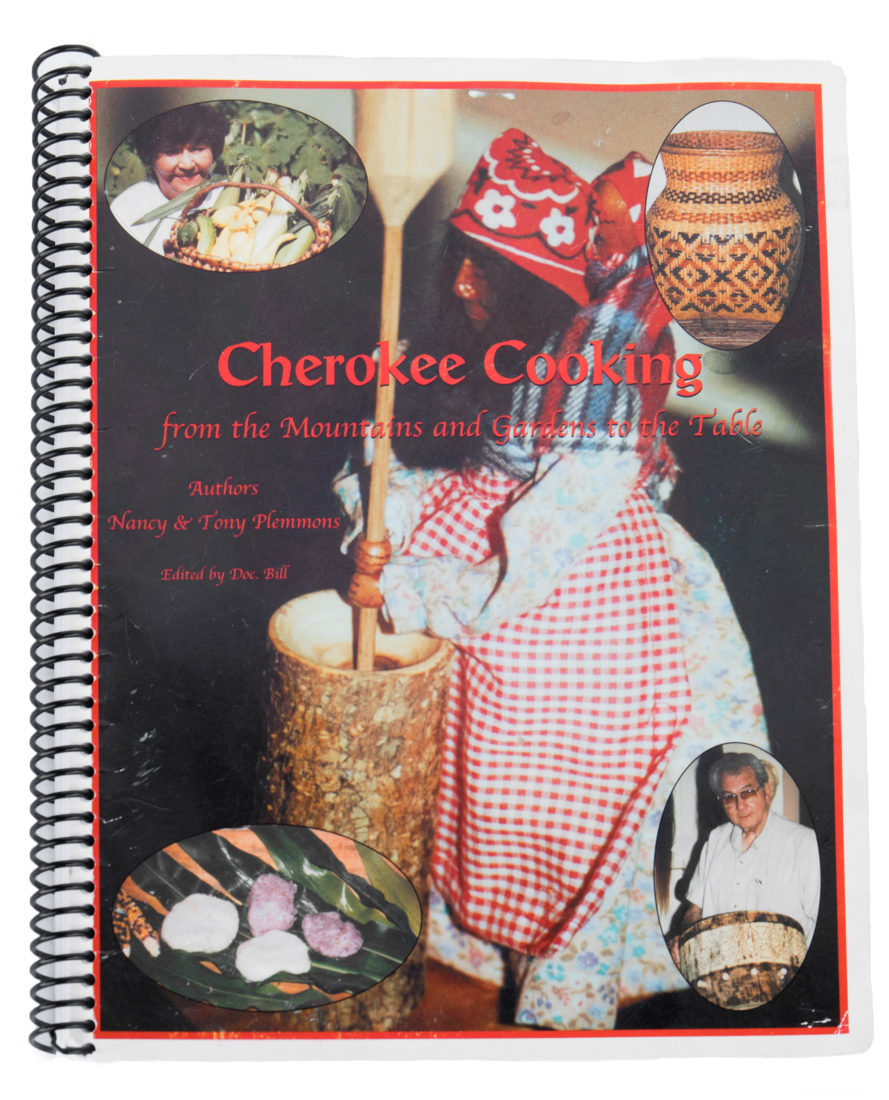

Thomas, Nancy, Tony, and a group of tribal elders collaborated on Cherokee Cooking: From the Mountains and Gardens to the Table, a spiral-bound collection of recipes and cultural knowledge that they self-published in 2000. Thomas was the editor. Plemmons is the last surviving contributor. Almost two decades after she sat down to share her family recipes for sumac lemonade and hickory nut soup, I joined her for a meal and a conversation.

Photo: Courtesy of Nancy Plemmons

Nancy Plemmons.

What, to you, are the essential ingredients and flavors of Cherokee cooking?

It has to be bean dumplings [also known as bean bread], fatback, and sochan. Cherokee cooks used to make cornmeal dumplings without beans, too, and we still do. Those basic dumplings are probably older. Cherokee people are also known for eating pork, because it’s all we had for a long time. We didn’t have beef at all. It was pork, chicken, and fish you could catch.

What about native meats, like bear or venison?

They used to be part of our diet, but not much of that goes on now because everything has been so restricted. Bear season and deer season, you know.

Tell me more about sochan.

Sochan is a wild plant that we harvest in the springtime. April, usually. You have to know exactly when to pick it, because when it’s too small it doesn’t have any taste, and when it’s too big it’s bitter. It’s full of vitamins. Everybody on the rez eats it. I have a few packs in the freezer right now. You cook it in fatback grease, and that’s where you get your seasoning. People are so scared of pork fat anymore that they use olive oil, but it’s not the same. Ramps are a spring tonic, too, but I don’t like ramps. Then there’s branch lettuce, but you can’t find it anymore hardly. There was a place up in the national park where you could pick it, but they stopped us from doing that.

Why have ramps and morels gone mainstream, but sochan hasn’t?

For one thing, sochan is an acquired taste. It’s strong, and it doesn’t taste like any other green you’ve ever had. If you don’t parboil it long enough, it’s bitter. Also, white cooks just don’t know what it is.

White settlers adopted so many ingredients and dishes from the people who were already living in these mountains, from poke sallet to cornbread. What’s a dish you’d still only find on a Cherokee table?

Oh, maybe pig’s feet with hominy. We love hominy, because we love anything to do with corn. I love homemade hominy, but it’s an all-day thing to make in a big pot with hickory ash and nobody does it anymore. Once you’ve eaten homemade hominy, it’s hard to settle for canned.

What do you do with hominy?

I usually use it with pork. I put it in pig’s feet or I put it in spare ribs. One man told me he put it in with his pork chops. Hominy goes well with any pork dish.

What are your go-to recipes from Cherokee Cooking?

I like the corn and onion fritters. That’s one of my favorites. Of course I cook beans and things like that, and poke sallet. I like poke sallet.

Last time we talked, you said you were optimistic about the future of traditional Cherokee food and culture.

I still am. The older cooks are teaching the younger ones how to cook traditional food. Our culture is starting up again. It was gone for a while. Now I think it’s getting stronger. We’ve been through the hard times, and here we are on the other side. The Creator has a plan for us, and I think this is it.

What can the rest of us do to help—if anything?

The biggest thing is to stay out of the way. Just let us do.