In Fletcher Williams III’s hands, Spanish moss, pulled down from a live oak, transforms into a brush saturated with paint. Discarded picket fences twist and turn in a sculpture that reaches to the sky. Stems link into a blanket beneath palmetto fronds curled into roses. Williams collects these familiar textures of his South Carolina Lowcountry home, then reimagines them and reshapes their forms. “I’m not sure if the material comes first or the idea,” Williams says. “But I let the materials lead most of the time.”

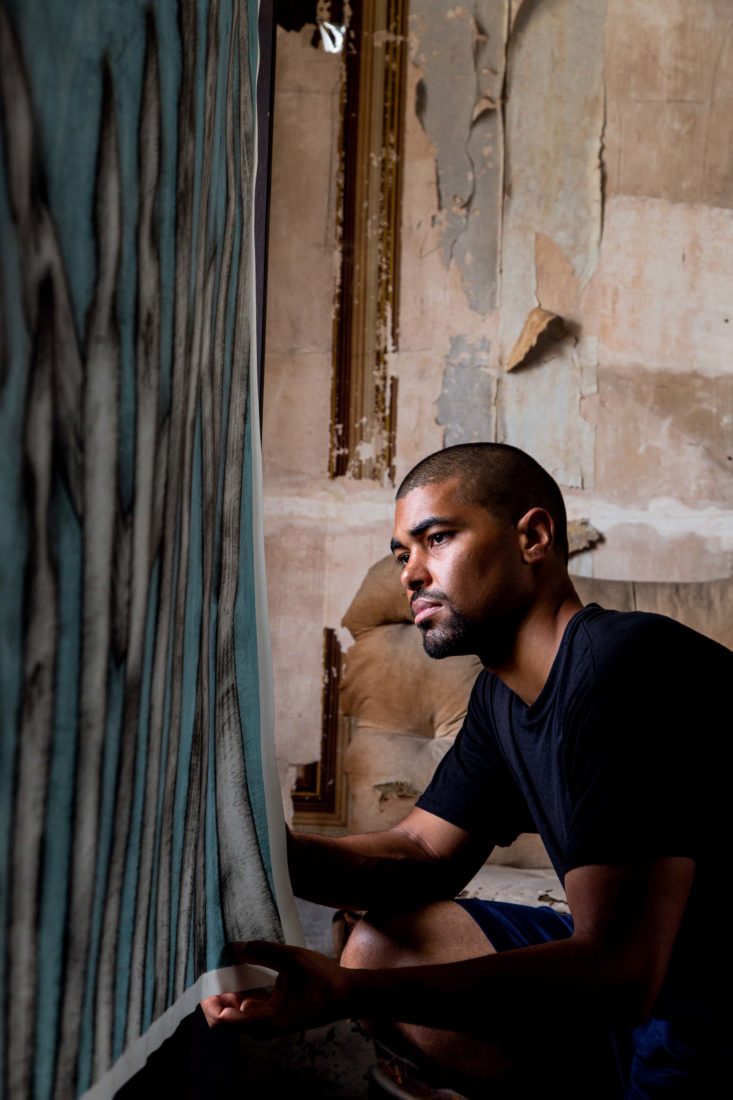

This past summer, Williams impressed Charlestonians and visitors with his sprawling Promiseland exhibition of installations, sculpture, and works on paper placed amid the peeling wallpaper and gilded mirrors of the Aiken-Rhett House Museum and in its high-walled work yard, once an urban plantation the governor of South Carolina owned in the mid-1800s. Williams used fences as the subjects of large-scale paintings, created with handfuls of that Spanish moss as his paintbrush, and he stood fence pickets along the same route that an enslaved cook would have walked up a back staircase. “A white picket fence has always represented the idea of aspiration, of a dream,” Williams says. But it also represents questions. “What’s beyond the fence? Are we scared to get a little too close?”

The lauded Lowcountry artist Jonathan Green, who for nearly forty years has painted and exhibited vibrant scenes of Gullah culture, walked through Williams’s exhibition in reverence. “I was moved at how a young artist, a man of the space and presence and also the face of history in Charleston, could create works that were like characters in this old house,” Green says. “His work showed what artists can do to give a face and life to so many important cultural institutions in this city.”

Although he’s just thirty-three, Williams has already experienced the epiphany some artists find late in their careers—that leaving home and then returning can rumble ideas to life. At the Cooper Union art school in New York, Williams built on his technical skills but was particularly affected by the ideas of the author Toni Morrison, who wrote, “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.”

Growing up in North Charleston, Williams rode his bike along trails, searched for turtles, and earned a few bucks by meticulously cutting his neighbors’ lawns. As a middle schooler, he surprised his mom by building an entire shed. “It just felt right to put things together,” he says. “It all seemed intuitive. Well-made things fit the way they should.” His teachers at Trident Technical College encouraged him to pursue art further in New York. He found creative ways to support himself: After returning to Charleston in 2013, he took a job driving a hotel shuttle. He talked with downtown tourists and urged them to chat with and buy from the children who sell palmetto leaves twisted into roses. When he left that job and devoted himself full-time to making art, Williams explored how the handmade roses connected the kids, and him, to a long, long line of African American ingenuity and craftsmanship, and for his Promiseland exhibition, he wove together three thousand palmetto roses as an ode to that legacy.

Williams’s advisory council spans beyond artists and into the world of practical problem-solving in which he grew up. He counts among his top gurus North Charleston hardware shop owners, palm leaf foragers, and auto body specialists, who spitball ideas with him: how to work with old tools, how to bend rebar, and how to pick just the right paint to spray onto rusted metal and wood. In turn, a new-to-fine-art crowd shows up to support him—many visitors who toured Promiseland told Williams they had never been to an art exhibit before, or until then had never set foot inside the historic Charleston mansion. “Young artists like Fletcher are creating a new Charleston Renaissance,” Green says. “He farms the area, yes, but he’s also a hunter and a gatherer who can draw, paint, and sculpt. Fletcher can conduct all the instruments.”

Up next, Williams hopes to find a studio in which to build his large-scale artwork, to install more public art, and to continue to connect artists, audiences, and craftspeople in unexpected ways. “There’s a lot to discover in Charleston,” he says. “I don’t think it would be a curse if I interacted with this landscape and made work here forever.”

Collect Fletcher Williams III, from his Picket Fence series, here.