It’s a child’s game. Turn yourself over to an imaginary set of circumstances. Everything you need to know is in the script. Read it three hundred times. Walton Goggins says those are the simple keys to acting, wisdom he gleaned from studying with the acting coach Harry Mastrogeorge for a decade. Such lessons have paid off. Goggins has appeared in some of TV’s best, from the gritty dramas The Shield and Justified to the indelible HBO comedies Vice Principals and The Righteous Gemstones, which will return for a second season. On the big screen, he’s part of Quentin Tarantino’s stable, with memorable roles in Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight. And last year, Goggins got his own series on CBS, The Unicorn, in which he plays a widower in Raleigh raising two daughters while trying to date again. CBS has renewed the show.

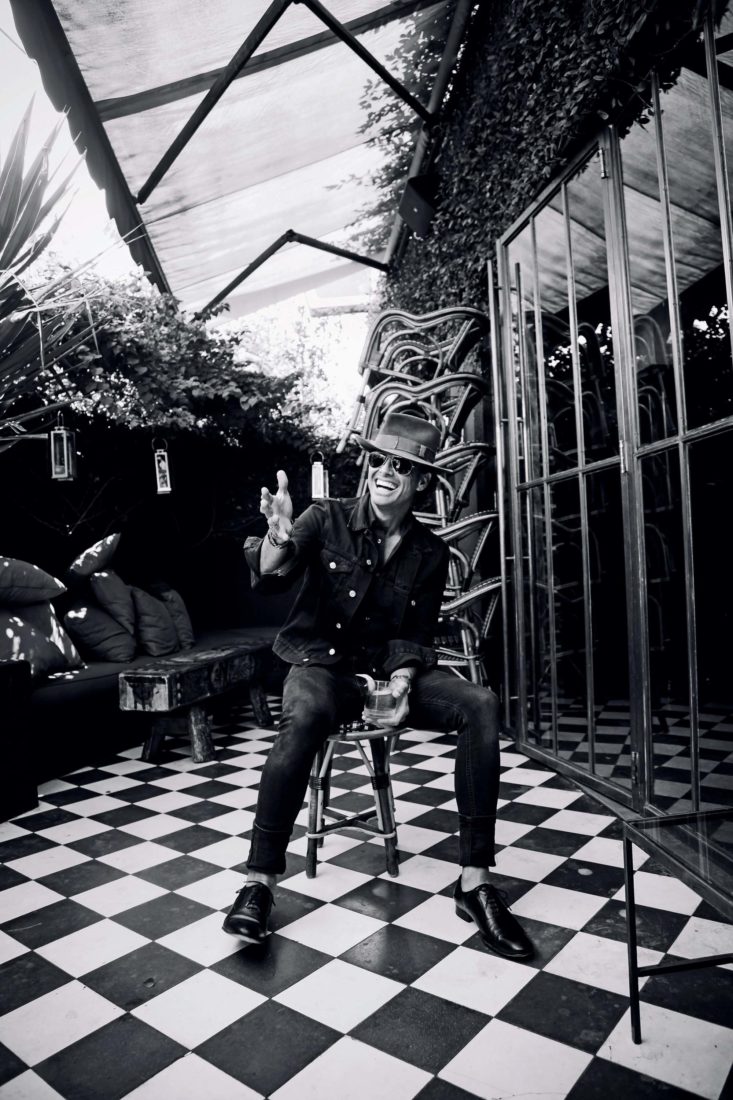

Born in Alabama, Goggins grew up in Georgia and moved to Hollywood at nineteen, working at LA Fitness and starting a valet parking business while taking acting classes and auditioning. Now forty-eight, he co-owns Mulholland Distilling with his friend Matthew Alper.

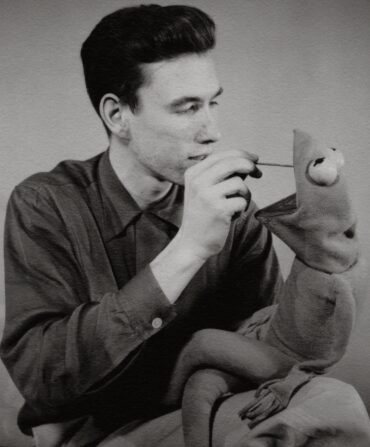

I first met with the actor over whiskey at Bar Stella in Los Angeles. In the midst of the pandemic, we caught up by phone and started by talking about our mutual obsession with The Andy Griffith Show.

Like Andy Griffith, The Unicorn takes place in North Carolina, and you even play a widower dad.

That’s right. I grew up watching The Andy Griffith Show in reruns. It was a seminal thing in my life. And I looked at it again in preparation for The Unicorn. In fact, my son started watching it with me.

Has it aged well?

The people who made that show were really putting something wonderful into the world. It’s unapologetic in its earnestness and sadness, but it’s also uplifting. I saw that and thought, “Why can’t we do that in the year 2020 on network television? We can do that.”

How did the South impact your career?

I never appreciated my culture and my people until I moved out here away from it. All of a sudden, the things that I wanted to get away from became very important. My accent gave me an opportunity to sustain myself. At first, there were just roles playing dumb hicks. It’s no different than an Italian actor from New York who moves to Los Angeles— you’re going to play a mafioso. And if you’re from the South, you’re going to play a redneck. Those parts gave me enough free time to study. Once I started getting some power, I made movies with Ray McKinnon, who’s from Georgia. We did stories about our childhoods and what the South meant to us. We started with The Accountant, a short released in 2001, and it won an Academy Award.

You took playing a redneck to another dimension as Boyd Crowder on Justified, which was set in Kentucky.

Boyd allowed me to give a platform to people from rural America. I wanted them to see a person who, without an education, was the smartest guy in the room. Those were the people who I knew growing up. So often people from different regions in this country are reduced to a very narrow interpretation. I wanted to blow that out of the water and to make people proud, in a way.

Whiskey became an important part of that show. Is that what inspired you to start Mulholland Distilling?

Well, I’m not going to sell toothpaste, you know? And I’m not really good at selling anything. But I am good at living my life in a certain way, and I think people from the South by and large have to sign a contract when you’re born that when you’re of age, you have to have a sundowner at night. When my friend Matthew Alper, who was one of the best cameramen in the business, said he wanted to start distilling, I said, I’d like to go on this journey with you.

It seems to come naturally.

I love drinking with people, and I’ve done it all over the world. Sneaking a beer with some Indians outside of Jaipur during the week of Holi. Having a glass of wine in Namibia when I was doing Tomb Raider, hanging out with members of the Himba tribe on the Angolan border. I love imbibing with people, hearing their stories.

What makes a great cocktail?

Simplicity. It’s like the best George Jones song—three chords and the truth. For me, it’s whatever liquor I choose, a simple syrup, and citrus. I do love a martini as well.

In 1997, you appeared in Robert Duvall’s movie The Apostle, about a Pentecostal preacher. What did you learn from him?

Authenticity. To not talk down to your audience. To be truthful with the story that you’re trying to tell and the place that you’re trying to tell it from. He also taught me to have fun with storytelling. And Bobby loves the South.

You play his assistant, Sam, and when Duvall’s character gets arrested, Sam becomes a born-again Christian. Your performance of that moment is stunning. How much of your conversion was in Duvall’s script?

Bobby is a dear friend and a mentor, but I can safely say that none of that was on the page of the script he wrote. When we got back to Los Angeles after shooting, he took me to lunch. “Son,” he said, “I don’t know if acting is what you want to do for the rest of your life, but it should be because you feel deeply. You can’t manufacture that. It’s either in you or it isn’t. What you did in that scene made my story.” That’s the biggest compliment I could ever receive from anyone, let alone my hero. I was twenty-four years old, and he changed my life.

Whom did you look up to growing up?

Burt Reynolds. Burt made movies in Atlanta, and I remember when Sharky’s Machine was being filmed in the Peachtree Plaza downtown. That was extraordinary to me. He was a real folk hero—an icon, man, to people from the South.

On Vice Principals, your character was a conniving high school administrator named Lee Russell, which sounds like a Southern name.

Yeah, “Lee Russell,” absolutely. I loved making Vice Principals. The creators, Danny McBride and Jody Hill, are from Virginia and North Carolina. The executive producer and director, David Gordon Green, is from Texas. There’s this shared kind of sense of humor that is part and parcel of being from where we’re from. Nobody makes me laugh the way somebody from the South can make me laugh.

This article appears in the August/September 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.