Proud Larry’s is Oxford, Mississippi’s communal living room, where Ole Miss students mingle with professors, writers, and other assorted locals. A restaurant by day and music club by night, it has a warm vibe with a weathered wooden floor that’s probably seen a tanker or two of spilled beer. Not to mention shows from such big names as Elvis Costello, Warren Zevon, the Black Keys, and the North Mississippi Allstars, who were basically the house band for a good chunk of this century’s first decade. And on a dreary Friday afternoon in January, two legends in the making, Cedric Burnside and Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, are wearing wide grins while trading blues licks on acoustic guitars just before sound check. Later tonight, the club will clear out all of the tables for an Ingram show that has long been sold out.

Burnside comes from North Mississippi blues royalty. Fluent in the drums as well as guitar, the forty-one-year-old is the grandson of Hill Country icon R. L. Burnside (whom he calls Big Daddy). Ingram, who just turned twenty-one, is a guitar prodigy hailing from the cradle of the blues, Clarksdale, in the Mississippi Delta. Despite the fact that Burnside is almost twice Ingram’s age, the two share a strong kinship, a musical bond born from the searing, hypnotic sound known as the blues. They also each carry the weight of keeping their respective traditions alive. While genres like Americana and country are loaded with up-and-coming artists, fresh faces playing traditional blues have been harder to find. In the Hill Country especially, which also gave rise to Mississippi Fred McDowell and Junior Kimbrough, outside of a few families, there’s been a dearth of emerging young talent. “I do worry about it becoming extinct,” Burnside says. “But there’s someone out there, we just haven’t found them yet.”

Burnside and Ingram slide into a booth on the second floor of Larry’s after Ingram’s sound check gets cut short (the bassist is late). “Gonna do it on the fly, I guess,” Ingram says. Talk turns to the upcoming Grammy Awards. Burnside has been nominated three times before, and Ingram is flying out to Los Angeles tomorrow for his first ceremony, where he’s nominated for Best Traditional Blues Album. (The award would end up going to seventy-nine-year-old Delbert McClinton.) “I’m nervous as hell,” Ingram says. Burnside nods. “It’s great to be nominated, and it definitely takes you to the next level,” he says. “But I always tell Kingfish, he’s gonna go far because of how humble he is. Big Daddy always told me, ‘You think you’re a big shot, but you ain’t nothing but a shell shot.’” The table erupts in laughter.

The pair met when Ingram was fourteen, at the Sunflower Blues Festival in Clarksdale. Ingram watched Burnside’s set from the side of the stage and approached him afterward. “He told me he could play,” Burnside says, laughing, as Ingram buries his head in his hands. “And when I saw him play for the first time, my mouth was on the ground. His fingers were moving so fast.” While Burnside honed his chops at Big Daddy’s house, Ingram started playing in church as a young boy while taking guitar lessons at the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale. Before long, he was booking sets at the top clubs in town, Ground Zero and Red’s. “My dad showed me a documentary on Muddy Waters, and that’s all I needed,” Ingram says. But he didn’t have much company. “All the people I grew up with wanted to be rappers or athletes.”

“To be a blues musician, you need to be dedicated to the form and tradition and not expect to get rich. That’s what Christone is. The blues chose him. As John Lee Hooker said, ‘It’s in him, and it’s got to come out.’”

“Blues is not in fashion these days, and not many younger people are exposed to the blues,” says Bruce Iglauer, the head of Alligator Records, the blues-focused label that signed Ingram. “If the blues were a little more part of the mainstream of popular music and heard a little more on the radio, there would be hundreds of young bluesmen and -women bringing their own personal visions. To be a blues musician, you need to be dedicated to the form and tradition and not expect to get rich. That’s what Christone is. The blues chose him. As John Lee Hooker said, ‘It’s in him, and it’s got to come out.’”

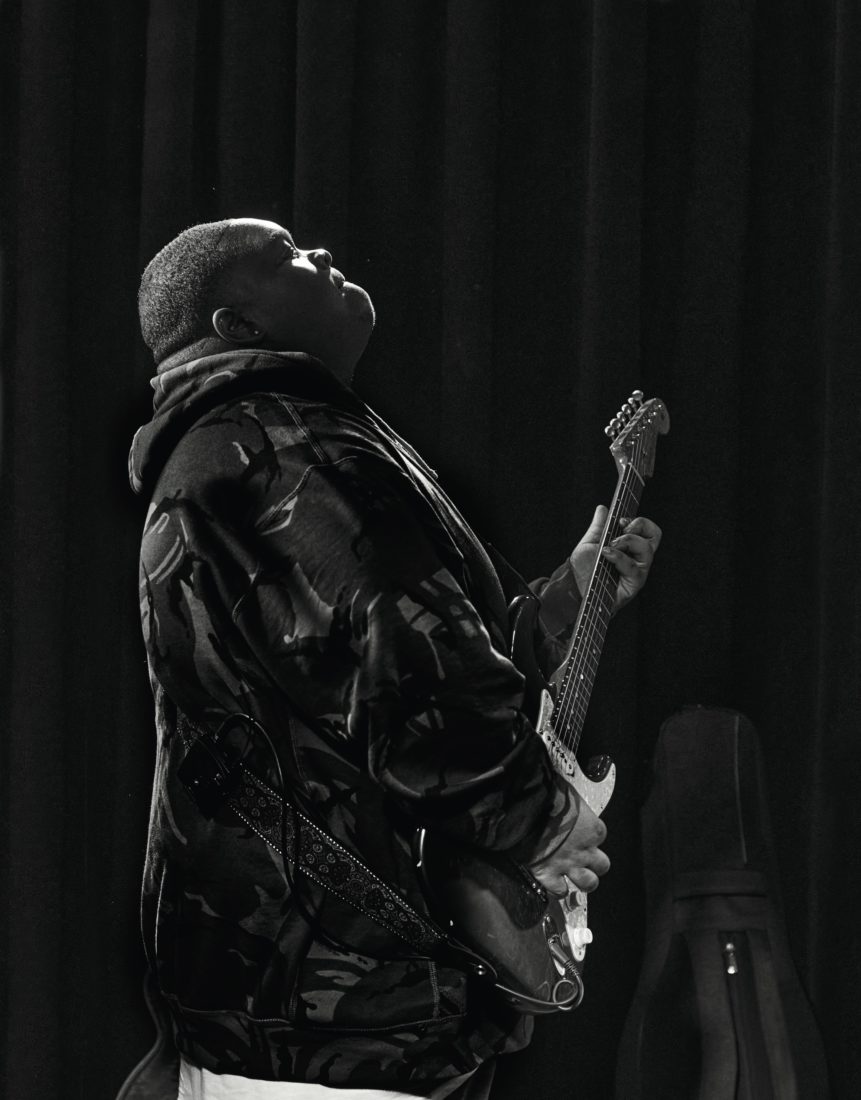

When the show starts a few hours later, the club is bursting, the thick damp air heaving with booze-fueled revelry, something like the Grove on a football Saturday. Burnside plays drums for his uncle Garry Burnside’s opening set as the crowd hoots and hollers to the mesmerizing rhythm. When Ingram steps onstage, the joint becomes frenzied, cell phones held aloft to capture the moment. Ingram leans into the smoldering groove of “Before I’m Old,” waiting barely two minutes before peeling off a solo that threatens to levitate the entire room. At least for tonight, here at Proud Larry’s, the blues is alive and well.