My dream to become a pilot came true in 1966, at the beginning of a five-year stint in the air force. I was twenty-two. Two decades later, I kept the pilot dream alive by buying a 1946 Piper taildragger that I named Annabelle.

During all my airplane journeys in Annabelle, I got “lost bad” only three times.

My original “lost bad” experience happened way back when I was a college ROTC cadet, flying a Piper Cherokee 140, a small civilian aircraft. My instructor, Mr. Keller, an understated and calm man, sent me off on my first solo cross-country flight (not technically across the country—an aviation term for a flight between two airports more than fifty nautical miles apart). The journey had three legs—from my home base of Raleigh-Durham (not yet international) Airport in North Carolina to a small airfield near Fayetteville where I’d land, then on to a larger airfield in Wilmington, and then back home. For navigation, I would be using only a map, a heading indicator, and a clock. Those were the rules. On the first leg, I confused minutes-into-the-flight with miles-into-the-flight and started looking for my destination airfield after I’d passed it.

Lost bad. There was a river down there on Mother Earth—but not on my map.

Wait—an airport! That must be it. I started a landing approach. Thank goodness, finally…wait, near the airfield: army tanks? I looked at my map. I’m over…I must be over…What? Fort Bragg?—a very restricted and…

Artillery training?!

Sweat dripping off my nose, I reversed course and eventually found (with luck) my first destination airfield near Fayetteville.

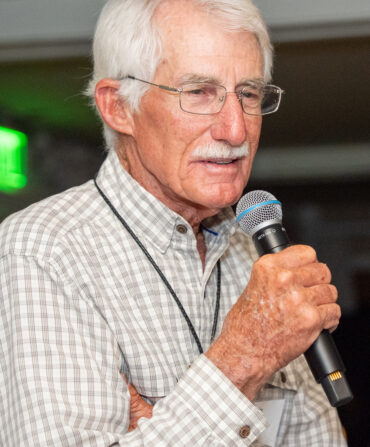

I landed, relieved. I studied my map, discovered my math error, took off, found Wilmington, landed, took off—and wondered what Mr. Keller might do or say when I arrived back home, very late. I couldn’t recall ever seeing him smile. I touched down at my home airfield, parked the aircraft, and walked into the flight shack. Mr. Keller was sitting, waiting. The sun had just set. Hands in pockets, I stood before him and mumbled something about getting lost. He did not grill, lecture, instruct, or counsel me. He said five simple words, then stood and walked by me and out of the building: “Did you learn anything, Edgerton?”

Now, about those three “lost bad” experiences in Annabelle—twenty years later.

Electronic and radio wave navigation aids were available back in the late eighties, but not in Annabelle. I couldn’t “fly the beam” to a tuned-in destination. There was none of this GPS namby-pamby stuff. You figured your wind speed and direction, the aircraft airspeed and speed over the ground, potential drift, and best heading. Paper maps were the bread of life. Along the way on your trip, you decided if you were getting off track.

The times I got lost bad in Annabelle happened on two trips that in one way or another were related to two of my writer friends: Tim McLaurin and Larry Brown.

The first occurred with Tim on a flight from Hot Springs, Virginia, to a grass airstrip outside Durham, where I kept Annabelle in a small wooden hangar. Because of magnetic forces in newly installed radio equipment (not related to navigation), my heading indicator was—unknown to me—about thirty-five degrees off. I’d had to abandon Annabelle at Ingalls airfield in Hot Springs a few days earlier because she wouldn’t start (very cold weather). Tim returned with me by rental car to retrieve her, and we brought with us an electric light bulb, an extension cord, and several sleeping bags. I placed the lit bulb inside the engine cowling, closed it, and covered it with sleeping bags. An hour later, Annabelle, warm to the core, cranked right up.

We took off and at about fifteen minutes into the flight, I said to Tim, sitting behind me, “Nothing on the map matches the ground. It’s got to be, I don’t know, the heading indicator—or something. I can’t figure out what could be wrong.”

“I have a compass.”

“What?”

“Right here.”

I turned and looked. Tim was pulling a necklace up out of his shirt. On it was a small round compass about the size of a quarter.

“I need to be flying on a heading of 170 degrees,” I said.

“You are headed, let’s see…about 200, 205 degrees.”

I turned left thirty-five degrees, held my heading, and soon saw a water tower. I circled it. SOUTH BOSTON, VIRGINIA was painted on the side. I knew the way home.

The next two lost bads were on a trip to Oxford, Mississippi, to see Larry Brown and his family. The trip there was scheduled to last six hours. I could fly about four hours on a tank of fuel, and so I scheduled one fuel stop, but somehow, somewhere, I got lost, recovered, and then after the fuel stop, got lost again. I got “straightened out” after finding a railroad track and following it until, as in the flight from Hot Springs, I spotted a water tower and then matched up the town on my map with the town below. Next, I found a railroad track to follow to Oxford.

I landed and took Larry’s two sons, Billy Ray and Shane, for a ride. After that I took Mary Annie, Larry’s wife, for a ride—but an approaching storm prevented Larry and me from flying together until the next day. We tied down Annabelle in a strong wind that preceded the storm.

I’ve gone back recently to read from my flight logbook, a small, wide book that I keep stored away in an old briefcase. Details of all my non-air-force flights are recorded there. I wanted to see if I ever mentioned getting lost on that first cross-country training flight or the other three times in Annabelle.

Nope. Only the place of takeoff, place of landing, flight duration—and in the comments section, I only included names of passengers, no details as I sometimes recorded with other flights.

In my third novel, The Floatplane Notebooks, Uncle Albert is challenged by his son Thatcher after Albert records in a notebook the details of a “test run” in his yet-to-fly floatplane at Lake Blanca. What had happened was that one of two chain-saw engines wouldn’t start, the rudder got “caught,” and the airplane ran in a circle on the water and grounded itself in dirt and grass.

Thatcher: “You wrote down that it was successful… You didn’t write…about the engine not starting.”

Uncle Albert: “No need to. I got it straightened out. That’s why I didn’t write it down. I got it straightened out.”

It’s okay if you get lost bad and don’t tell. But it helps to get it straightened out. Most people will understand the silence. Especially pilots.