In small-town Florida in the 1950s, young women had three options, Vicki Smith says: “You got married, went off to school, or you became a Weeki Wachee mermaid.”

Smith, who grew up near Weeki Wachee Springs, chose the last option. At age 17, she began swimming at the longtime Sunshine State attraction. Today, at 78 years old, she is considered the world’s oldest performing mermaid.

“Whenever I sink beneath the surface of that beautiful water, I don’t want to get out again,” Smith says. “There’s a freedom there. The movement of the current feels like silk wrapping you, and the bubbles become silver pearls all around.”

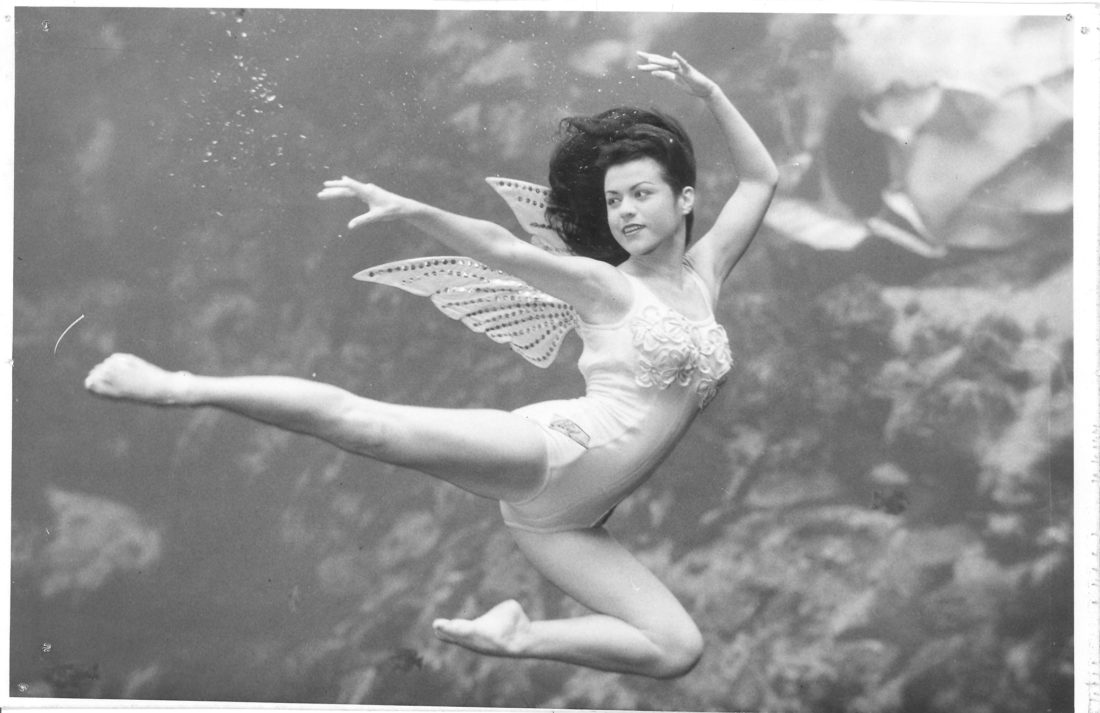

Photo: Andrew Brusso

Vicki Smith performing recently.

Forty-five minutes north of Tampa, Weeki Wachee is by far the most popular (and still running) of a group of kitschy dancing-mermaid tourist traps that popped up across the South in the midcentury heyday of road trips and car travel. The entire springs and amphitheater became a state park in 2008, but the shows originated as a private business.

Photo: Florida Memory

The spring and theater in 1947.

In 1947, entrepreneur Newton Perry founded the mermaid attraction in a sandy-bottomed natural pool that connects with the springs and a seven-mile river. Perry carved out a limestone theater where viewers looked through glass and into crystal clear water. He was also strategic in his early marketing—within a year of opening, Hollywood producers paid the park a visit. It was then used as the setting for the 1948 film Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid.

Photo: IMDB

A poster for the 1948 movie filmed at the Florida attraction.

The attraction’s rise and mystique was all about timing, says Carolyn Turgeon, author of the new book, The Mermaid Handbook, which shares mermaid lore and interviews with performers from around the world. “You take beautiful springs in Florida, the development of underwater camera equipment, and the fact that Hollywood came calling early,” she says, “and you get a picture of why the place was and is considered very glamorous.”

Although “Weeki Wachee” comes from the Seminole language and means “little spring,” it’s so deep in parts that its lowest point has never been found. Performers swim 16 to 20 feet below the surface, and because the setting is part of a river, fish, manatees, and other aquatic wildlife do show up for visits.

“At first, we did not swim to music underwater, and there was no sound piped in,” Smith says. “But someone would do hand gestures through the windows, like if there was a gator in the spring or a snake nearby, they could motion to us and we knew to get out.”

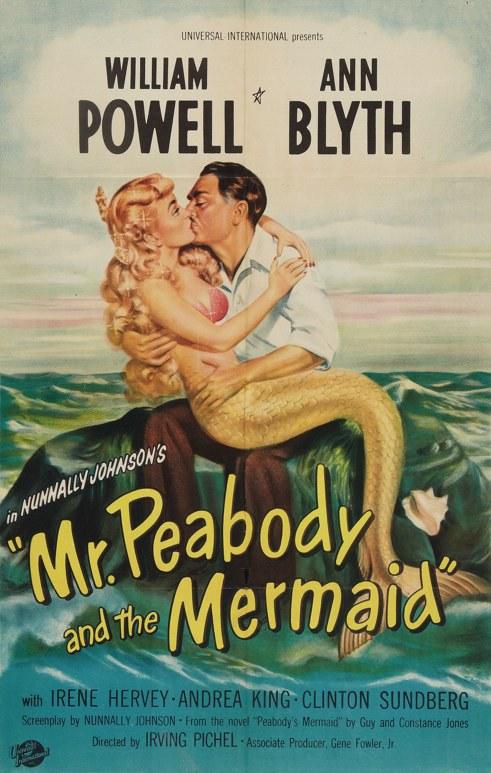

Photo: Florida Memory

A vintage advertisement for the Weeki Wachee mermaids.

The breathing hoses Perry developed allow mermaids to stay underwater for long periods of time without having to carry around a tank. “We would swim over to breathe from the air hose on each side of the springs,” Smith says, “And then swim toward the audience and do tricks like eat a banana or drink a whole bottle of pop. Today’s girls each have their own air hose, but back in the 50s, we had two air hoses on each side, out of sight of the audience.” Air flows from compressors and performers take frequent sips to stay underwater.

Photo: Florida Memory

Performers drinking Grapette underwater in 1949.

More than 100 million gallons of fresh water bubble up through underground caves each day, maintaining a crisp 74-degree temperature. “It’s cold, and you stand there, and you look at it, and you can think of a million reasons why you don’t want to jump in,” Smith laughs. “But the minute you go under, you’re in another world. And you don’t want to ever get out again.”

Florida Memory

Early performers wore one-piece bathing suits and performed in front of small audiences, but today’s mermaids don costumes of shiny tails and bikini tops and swim four daily shows in front of a 400-seat auditorium. Mermaid camps—which Smith helps run—for both children and adults sell out quickly. If you’re hoping to catch one of Smith’s performances, she and a group of other “Legends” who swam from the 1950s to 1970s will perform multiple dates this year.

“I might not have the stamina I had when I was a teenager,” Smith says. “But I can still dance, eat a banana, and drink a pop underwater. Once a mermaid, always a mermaid.”