“We never said we’d never do it again,” says Patterson Hood of Drive-By Truckers. “We’ve just said ‘not now’ for years.” Well, as of today, “now” has a date: June 7 in Indianapolis, the kickoff to a thirty-nine-show tour in which the Truckers will play Southern Rock Opera, the band’s 2001 double-album masterpiece, from start to finish. It’s an announcement that’s something like the Holy Grail for longtime Truckers fans. Some of the album’s songs, such as “The Southern Thing,” “Angels and Fuselage,” and “Greenville to Baton Rouge,” have been rarely played or not heard at all in years.

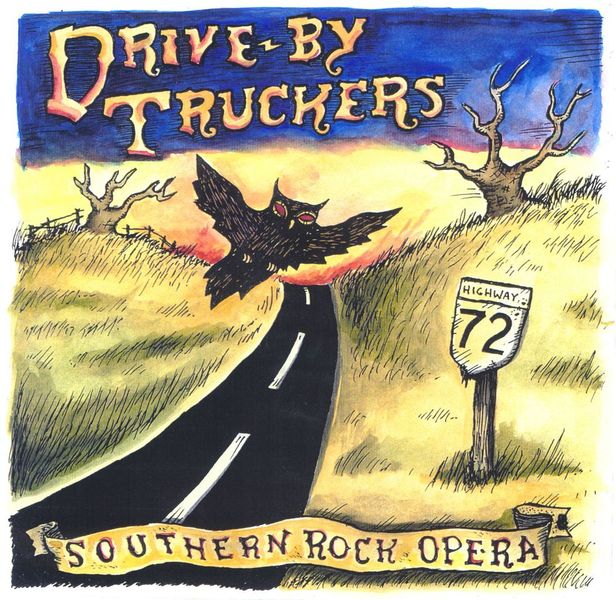

The album’s story is now legendary: Hood and bandmate Mike Cooley crafting a narrative about Southern identity through the eyes of a native son who becomes a rock star like his idol Ronnie Van Zant of Lynyrd Skynyrd. Along the way, the songs reckon with the South’s history, race relations, and youthful indulgence, and rock just as hard, if not harder, than Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers. The project took them nearly six years to record, leading to a few near break-ups, and it remains a work of colossal achievement, one that, in this writer’s opinion, stands among the greatest rock albums of all time.

Read our exclusive interview with Hood below on bringing the album back to the stage, and click here for tickets and dates.

So, the obvious question: Why now?

It’s almost like a perfect storm of different stuff. We’re not ready to make a new record yet, because we’ve all been doing some other things. People have been asking for years, and Cooley has always said, “We’ll do it when we can do it on ice” [laughs]. That was a great line in the sand. But we haven’t figured out how to do it on ice, though I’m still hanging on to the dream. We talked about it for five years until we just had to follow through or else we were going to look like assholes. So, it just seemed like a good time to do it this year.

Have you gone back and relistened to the material?

I hadn’t listened to it in a long time, but it’s been fun. We’ve actually been practicing some songs, which we never do because we’re like the most disciplined undisciplined band.

We’re not necessarily trying to play it exactly how we played it twenty years ago. But a lot of the stuff is still timely. It’s all set in the seventies and early eighties, as far as the songs’ themes, but in some ways, it’s more relevant to what’s happening in the news now than in 2000 or 2001. Because back then, sadly, I think we were all a little more optimistic that maybe we had moved past some of this stuff. But we’ve moved so far backward in the last decade, and it’s kind of horrifying to me.

“The Southern Thing” is the crux of the first part of the album, which digs into what being from the South means to people. How do you view the song now?

I think it’s one of the best guitar songs I’ve ever written. It’s just a 1970s prototypical arena rock, guitar-slinger song. But as a songwriter, I’ve always felt like it was a bit of a failure. I felt like what I was trying to say didn’t necessarily work. We don’t play it a lot. The hardcore fans know what we mean when we do that song because we can play it with enough context where I don’t feel like it’s being misconstrued. When I wrote it, I was trying to say that if you ask one hundred Southern people about the “Southern thing,” you would get one hundred different answers that often conflict with one another. After the record came out, we started to play these much bigger places in front of thousands of people, and when we started playing the song, there were people out there waving Confederate flags. We were mortified.

You’re from Alabama, and another notable track is “The Three Great Alabama Icons,” which addresses George Wallace, Bear Bryant, and Ronnie Van Zant, who wrote “Sweet Home Alabama.” Those were the three dominant figures in the state when you were growing up. Will you update them? Maybe Nick Saban should slot in there.

Ha! Maybe Saban should be in there. It’s not like George Wallace is part of the day-to-day conversation. But as bad as he was, he would be mortified by some of what’s happening today. I’ve actually met some of his family members. He has a grandson who has come to our shows, and I’ve spoken with him. He’s a cool guy.

The second part of the album takes off in a different direction, with a teenager living out his rock star fantasy.

It’s the glorification of the fun times you can have when you’re young and wild and drinking and partying too much. But there’s a dark side to that too, and we as people have gotten older and drink a lot less. Hell, Cooley and I have kids that are the age we were when making that record.

You guys have avoided nostalgia up until now, but playing the album from start to finish is perhaps the quintessential way to look back. Are there ways you can make it fresh?

We never write a set list or do encores in our regular shows, but for these shows we likely will take a break after playing the album, then come back out and perform a different set of songs each night. A couple of songs have been written since the record came out that are still part of the narrative, so we’re incorporating those into the show.

Really? What songs?

I don’t know if I want to say [laughs]. I will say that Cooley has always said “Primer Coat” [from the 2014 album English Oceans] was the same guy as the one in [Southern Rock Opera’s] “Zip City.” “Primer Coat” is a perfect song to do in this context because it hasn’t been played in eight years. And it’s a great song, so I’m pretty excited it’ll be played. But we’re not talking about any crazy reconstruction or trying to reinvent the past; we’re trying to acknowledge what has happened and who we’ve become. But reconnecting with who we were when we wrote it has been a fun part of the process.