Kelly Fields’s talent in the kitchen has led them all over the world—from their hometown of Charleston, South Carolina, to celebrated kitchens in Europe, the Middle East, and California, and then to New Orleans. “I love being in the South,” says the chef-owner of the bakery Willa Jean. “I love the variety of people I meet here—the variety of personalities, the variety of lifestyles, the variety of backgrounds—and how that all comes together, specifically in New Orleans, to be this beautiful pot that we all cook from.”

The South—and the food world at large—loves Fields right back. Since they opened Willa Jean in 2015, they’ve racked up best-chef accolades from local and national media, and garnered four consecutive nods as a semifinalist and nominee for Outstanding Pastry Chef at the James Beard Awards before clinching the top honor in 2019. Along the way, Fields became a pillar in the food and drink community, too, founding the Yes Ma’am Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to lifting up women in the culinary and hospitality industries.

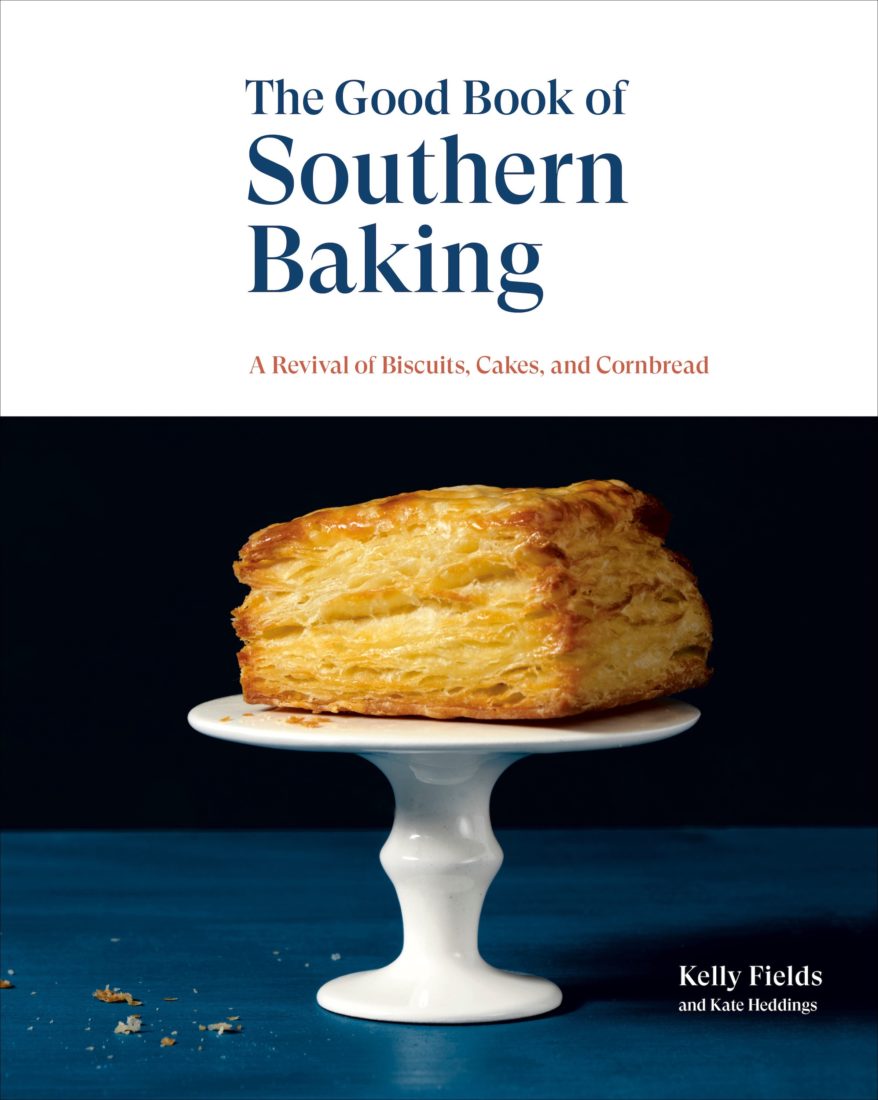

Their latest endeavor, a new cookbook called The Good Book of Southern Baking, builds on Fields’s trailblazing work, with recipes that range from the ornate, such as the Chocolate Chess Pie with Whipped Chocolate–Mint Ganache, to the easy, such as the treasure trove of tasty riffs on boxed cornbread. Clocking in at more than three hundred pages, The Good Book of Southern Baking is a tome worth its shelf space for experienced chefs and beginners alike. Here, we caught up with the renowned pastry chef about the cookbook, their Charleston childhood, and why lending a hand to the next generation of women in food has aided their own development, too.

What are your earliest memories of baking?

My mom baked most every week growing up, and I think the first very clear memory I have about baking is throwing a complete temper tantrum over it. [Laughs.] My mom was making carrot cake and zucchini bread, all in the same shot, and I was so upset that you would ruin cake with vegetables! [Laughs.] I threw myself on the kitchen floor. That is one of my very first memories. But we made cookies almost every week. My mom was always baking cakes, baking for the neighbors. My dad taught me how to make ice cream on a hand-cranked machine on our back deck. It’s always been part of how we cooked as a family.

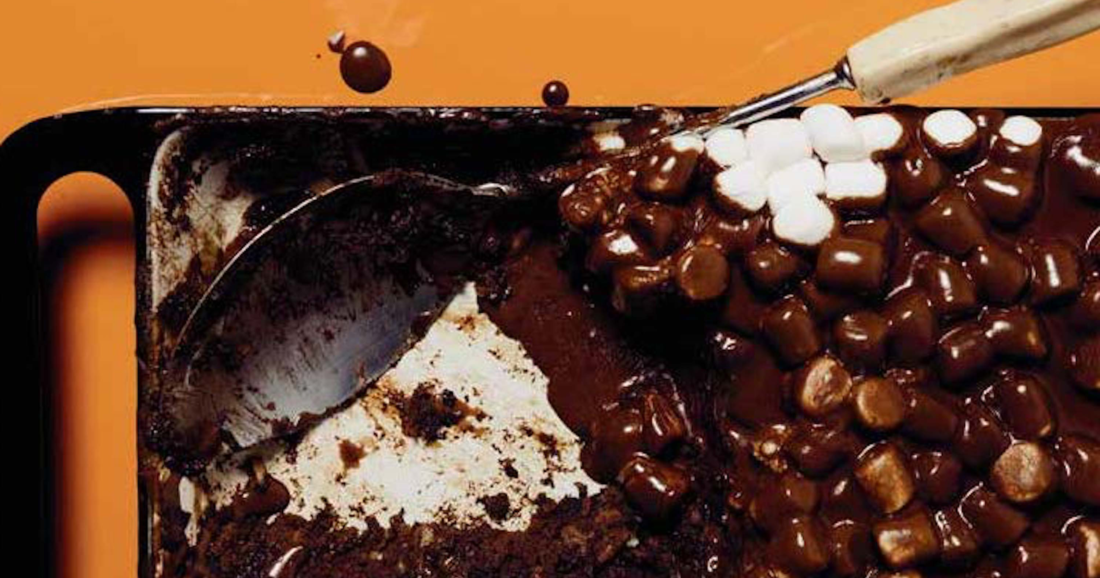

You mention your mom often in the book—one recipe you call out is her Mississippi Mud Cake.

I’ll say this to you, I have a very strong dislike of marshmallows. I always have. I have an obsession with texture, and that cake feels like one of the places where that started. Because when it’s warm, it eats different: You had this fudgy cake, and the marshmallows, and fudge, and all these different little things going on. So I would just heat and eat the tiniest sliver at a time.

GET THE RECIPE: MOM’S MISSISSIPPI MUD CAKE

That obsession with texture has probably served you well: Baking is such a precise kind of cooking …

It’s not! It’s not. No. I mean, you think about grandmothers in the South—they cook with a handful of this, a dollop of that, and a pinch of this. There were no gram measurements. It was all so intuitive. I mean, obviously, some pastries are very specific, and very exacting, but I think Southern baking is an intuitive thing that you have to be connected to.

What’s your favorite thing to make for breakfast, and what’s your favorite thing to eat? Are they the same?

It’s all pancakes. Pancakes shouldn’t really have a spot in that book—they’re not a baked good—but I just love them so much that I refused to write a book without pancakes in it. I love, love, love pancakes. That’s the only reason they’re there, and I have gotten more emails or messages or tags about those pancakes than anything else in the book so far.

What do you think made this recipe particularly special?

I mean…[they’re] not super sweet, [have] a little bit of tang, and just the fluffiness of them: I like them super fluffy, so I separate my eggs and whip them. They’re really simple, they’re just delicious.

GET THE RECIPE: KELLY FIELDS’S BUTTERMILK PANCAKES

This book feels like the definitive Southern baking book—a great gift for someone just starting out. If a beginner were approaching these recipes, what are some ways they could feel like they’re being creative in the kitchen without messing up the final result?

There aren’t a lot of rules. That’s the problem with baking right now, is that people feel like there are so many rules that they forget to have fun. And I think that’s really silly! Baking should be fun. Even though what you get might not look like a Pinterest board, it’s still going to be really delicious if you’re using really delicious things. If you’re going to try a recipe, the keys for success are to read the whole thing before you begin, start to finish; don’t overthink any of it—especially in my book, none of it needs to be overthought; and mostly, don’t forget to have fun.

Speaking of fun: I loved that you, a world-renowned chef, included a whole segment on jazzing up boxed Jiffy cornbread mix. Why?

Jiffy cornbread is what I grew up with. There’s so much science in that. They figured out how to do cornbread, and the reality is, that’s all a lot of people have time for. I mean, maybe the pandemic’s changed that, but two years ago, when I was writing that list, we were all very busy people. [Laughs.] It’s a way for people to try new things. It’s easy, it’s economical, it’s fun. I do the same thing with boxed cakes. It’s like, they figured that out, but how do you make it better? How do you change it? How do you have a little bit of fun, and surprise yourself and others?

GET THE TRICKS: HOW KELLY FIELDS DOCTORS UP BOXED CORNBREAD

You mentor younger chefs with the Yes Ma’am Foundation. What are some of the biggest obstacles for rising culinary talent, and how are you trying to address them?

I’m only coming from my own experience, but for me—especially as a young, queer, female cook in New Orleans—mentorship wasn’t something that came until I had a certain level of perceived success. I think things would look a whole lot different if I’d had access to get in the rooms with people, to ask some questions, along the way. So I’m trying to make that a reality for chefs today: to “get in the room,” so to speak. We do grants for self-investment, for continued education: If somebody wants to go work at a winery, or go to conferences, or take a class, we’ll help them make that a reality. All of these women inspire me and remind me every time we interact that there is no ceiling to what we can do. These young minds that are just eager and enthusiastic and tenacious…there’s no dream that’s too big for them to accomplish. I fully believe that, and they convinced me of that—they convinced me that I could think that way about myself.