Lying next to the banks of the Big Coal River in Whitesville, West Virginia, sits a giant slab of black granite forty-eight feet long. Etched into the stone are the silhouettes of twenty-nine miners who perished in a 2010 explosion at the nearby Upper Big Branch mine, the country’s deadliest mining disaster since 1972. At the monument’s base are the words “Come to me, all you who labor, and I will give you rest.” It’s a stark reminder of the backbreaking, gritty determination of the West Virginia workers who toiled in a perilous environment.

Steve Earle has been to the monument, moved by its majesty as well as deep empathy for the families who lost fathers, sons, uncles, and friends, despite warnings of unsafe conditions. (The disaster led to a settlement of more than $200 million in 2011, and Massey Energy’s then-CEO, Don Blankenship, spent a year in prison for conspiring to violate mine safety standards.) “It was preventable,” Earle says. “An absolute tragedy. Once again the workingman gets squeezed for money.”

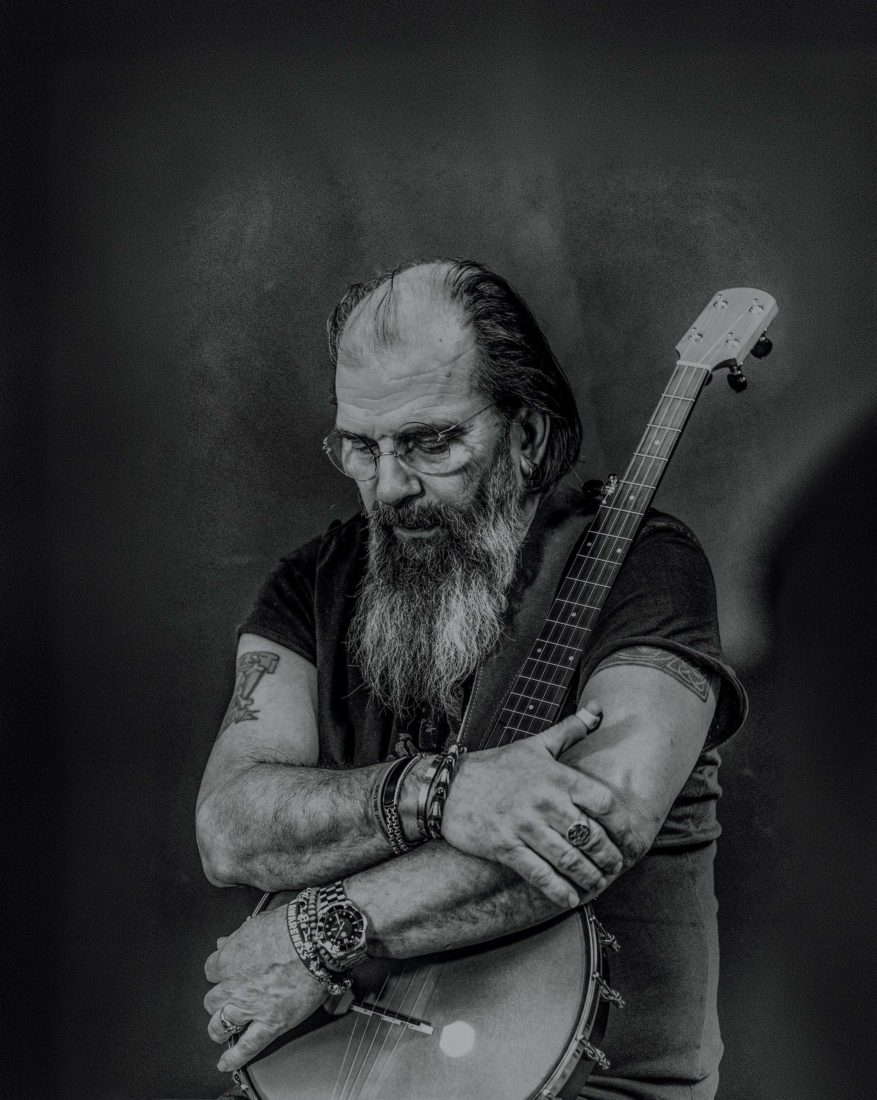

The acclaimed New York–based singer-songwriter has spent a good chunk of time in West Virginia recently. In 2015, playwrights Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen approached Earle to write the music for their documentary-style play Coal Country, a production of New York’s Public Theater. “This is a play that had to have music in it,” Jensen says. “There isn’t a songwriter who is more attuned to the workingman than Steve.” As the trio began to sketch out the story line, Earle joined the writers in conducting interviews with family members of the victims, and those stories make up much of the play’s dialogue. “People in West Virginia talk like this,” Earle says, in reference to his own Texas drawl. “Jessica and Erik didn’t. They thought having me there would help, but I don’t know if it did or not.” He’s too modest: Coal Country opened to rave reviews this past March, with Earle appearing in each performance as an Appalachian version of a Greek chorus, but the run was cut short due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The material Earle wrote, though, does double duty, as those songs make up the bulk of his twentieth album, the devastatingly poignant Ghosts of West Virginia. From the a cappella spiritual opener “Heaven Ain’t Going Nowhere” to the rollicking bluegrass of “John Henry Was a Steel Drivin’ Man” and “Black Lung,” Earle’s gravelly voice is at its most gripping, fueling evocative and heartbreaking character sketches. The crushing stomp of the album highlight “It’s about Blood” drips with an intensity that explodes as Earle howls the name of each of the twenty-nine miners who died.

It’s those hard-nosed workers whom Earle wanted to address directly with Ghosts of West Virginia. The singer has never shied away from being outspoken about his left-leaning politics, sometimes finding his concert T-shirts burning at the door of his tour bus after a show. With his classic albums Copperhead Road and The Revolution Starts Now, among others, he was singing to an audience whose views often aligned with his. But for Ghosts, Earle wanted to reach out across political divides. “This is a record for the people who didn’t necessarily vote the way I did,” he says. “Not every person who voted for Trump is a racist or an asshole, so we need to find something in common with each other. Otherwise it’s going to kill us.”

Despite his status as one of music’s most celebrated songwriters, Earle admits his favorite art medium is theater, a love of which he traces back to his grandmother, who became a costumer for the theater department at a local college near Jacksonville, Texas. Coal Country came at an opportune time, as Earle had been looking for some inspiration. “Having a project and a deadline is a wonderful thing for me,” he says. “I know songwriters who as they get older stop writing, and I have such a fear of that. I’m always looking for something to make sure I write the next song.”

In addition to the interviews, Earle spent days crisscrossing West Virginia to give the material on Ghosts a deeper sense of place and geography. And though he played more than 140 shows in 2019, he’s planning to limit his touring to spend more time with his son with ex-wife Allison Moorer, John Henry, who is autistic but thriving at the school he attends. But he’s hopeful that he can get back on the road this summer, with a handful of dates planned in the heart of the coal country of Kentucky, Virginia, and, of course, West Virginia.

“People who have seen Coal Country went away with a better understanding of who these people are,” he says. “With the songs on Ghosts, I’m trying to humanize them as much as I can. That’s the most important part.”

This article appears in the June/July 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.