Arts & Culture

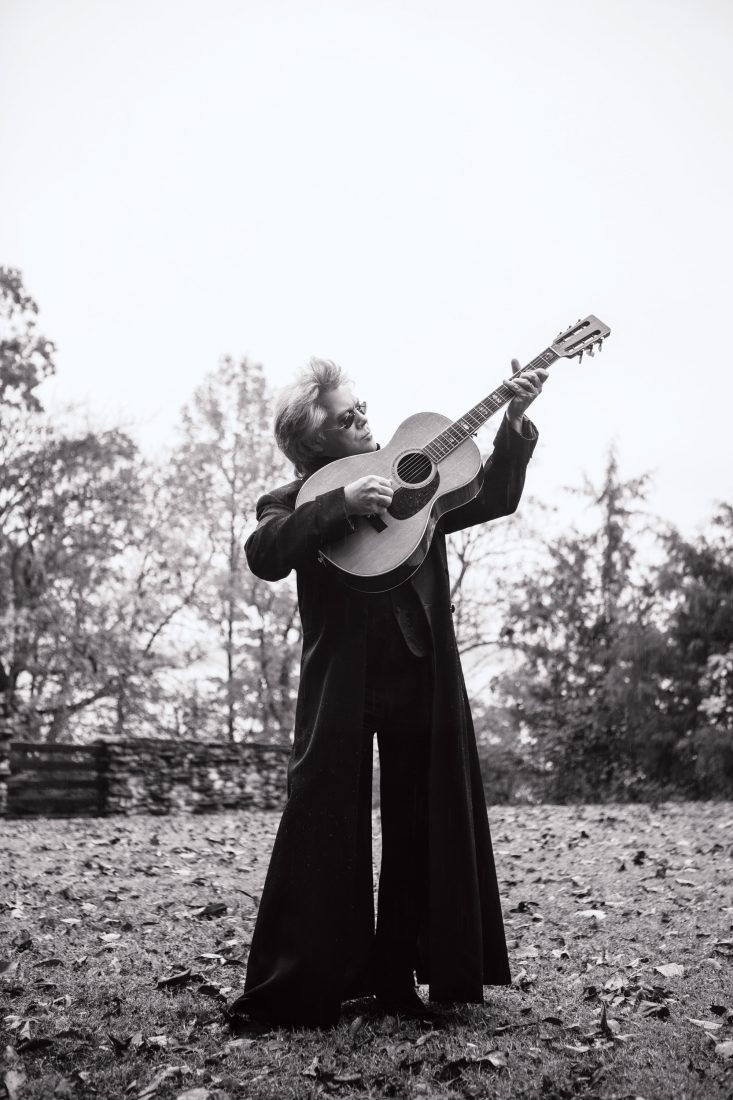

Marty Stuart: Memory Keeper

Marty Stuart may be one of country music’s greats, but these days he’s more concerned with preserving the legends of those who came before him

Photo: David McClister

It’s a frigid night in Fort Worth, Texas, and I am standing backstage at the two-thousand-seat Bass Performance Hall, where Marty Stuart and his band, the Fabulous Superlatives, have just opened for Merle Haggard. At seventy-seven, Haggard is showing signs of frailty—his wife and backup singer, Theresa, has already left her mike to fetch him water and his inhaler—and Stuart is almost hyperconscious of the time remaining with the greats of what he calls “real” country. “There so little of this left,” he says as Haggard launches into “Sing Me Back Home,” the 1967 hit that draws on his three years in San Quentin State Prison.” At one time, there was so much gold it was falling off trees, and now we’re down to a handful of doubloons.” What Stuart would never say is that a whole lot of people in the sold-out auditorium—as well as Haggard himself—would put him in the same exalted company.

A consummate showman and virtuoso mandolin player, Stuart was tapped at the tender age of thirteen to play in Lester Flatt’s band and took the stage alone at the Grand Ole Opry barely a week later, an honor most musicians don’t attain for years. Since then, his extraordinary range and reputation have landed him on stages with everyone from Pops Staples and Bob Dylan to Johnny Cash. At various times in their three-decade-plus friendship, he was Cash’s bandmate, son-in-law, next-door neighbor, and songwriting partner—the pair finished “Hangman,” a song on Stuart’s critically acclaimed 2010 album, Ghost Train, just four days before Cash died. In his review, the late, great critic Chet Flippo wrote that Stuart was the only musician in Nashville with the chops, credibility, and showmanship to bridge traditional country with, say, the likes of Taylor Swift or Carrie Underwood. Onstage in Fort Worth, he stands shoulder to shoulder with “Hag,” harmonizing and playing guitar on “Okie from Muskogee.” Afterward he tells me, “To lean up against Merle is like leaning against an oak tree—he empowers us.” But Haggard clearly feels the same way. “Marty likes to work in Nashville—I don’t,” he says. “But he keeps that town alive.”

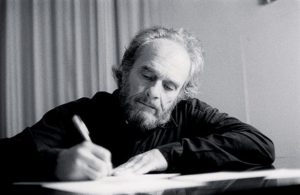

Photo: Marty Stuart

Merle Haggard

Stuart has photographed Haggard, performed with him dozens of times, and watched as the “Poet of the Common Man” inducted his wife, Connie Smith, into the Country Music Hall of Fame. During sound check at Bass Hall, he picks up Haggard’s guitar to show me the through-and-through bullet holes made by Haggard’s pistol when it “accidentally” went off on his bus. (“It enhances the sound,” Stuart says, laughing, “or at least the story value.”) But familiarity does not make him any less respectful. “In California, we had a day off and Merle and I wrote a song, ‘Blue Yodel #14’—Jimmie Rodgers should sue us. Two hours later we recorded it. Those days are precious.” The night before the Fort Worth show, Willie Nelson joined Stuart and Haggard onstage in Austin. “It was like being up there with Geronimo and Red Cloud,” Stuart says, “and we’re next. Our job is to honor the chiefs. We’re not astronauts or physicists, but we’re the keepers of all this stuff and we have to pass it on.”

When he says “stuff,” he means the musical traditions (not to mention the integrity and authenticity) he and the Superlatives have worked hard to perpetuate, though he has plenty of actual stuff, too. Over the last three decades, Stuart has amassed the largest private collection of country music memorabilia in the world, more than 20,000 pieces ranging from thousands of hand-embroidered suits by Nudie Cohn and his protégé Manuel Cuevas to handwritten Hank Williams and Roger Miller song lyrics and the pink boots Patsy Cline had on when she died. “He’s got a collection that rivals the Country Music Hall of Fame,” says Nashville talent agent Bobby Cudd, who represents Old Crow Medicine Show, a group Stuart discovered busking in a festival parking lot. “He’s also a torchbearer for country music, not just traditional or classical country music, but valuable country music. Come to think of it, he’s sort of a living museum himself.”

Photo: David McClister

A Nudie shirt worn by Hank Williams from Marty Stuart’s collection of country music memorabilia.

It’s true that Stuart’s entire life has been spent studying, documenting, living, breathing, and playing with pretty much everybody who has ever mattered in the world of country music (and gospel and bluegrass). Born in 1958 in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and christened John Martin, he was called Marty after Marty Robbins. He grew up watching Porter Wagoner’s rhinestone-encrusted suits “winking” at him from the family’s black-and-white TV screen and formed his first band when he was nine, playing songs like “Wildwood Flower” at Rotary Club gatherings. Even then, the precocious Stuart was all about tradition—he told the local Neshoba Democrat, “It’s hard for a country performer to make a living in a Beatles society.” In 1970, when he was twelve, he was given his first mandolin and saw Connie Smith perform her signature hit “Once a Day” at the Neshoba County Fair. On the way home, he told his mother he was going to marry Smith—and he did, twenty-seven years later in a ceremony on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

That same year, his daddy took him to a gospel show in Alabama where Bill Monroe gave him a mandolin pick and he met the Sullivan Family, a bluegrass gospel act whose members asked him to tour with them the following summer. “On my first day away from home, I saw the chain-smoking monkey at the Dixie Gas Station on Highway 45 South. Right then and there I was hooked.” When the Sullivans brought him home in time to start the school year, he said he felt like “the circus had dropped me off at the edge of town and kept going on without me.” But the feeling didn’t last long. He’d met a member of Lester Flatt’s band who invited him to ride up to a Labor Day festival in Delaware on Flatt’s repurposed old Greyhound. When Flatt heard him play, he offered him a job on the spot. “It was kind of like that scene in The Wizard of Oz where life goes from black and white to color all in one sweep,” Stuart says. By the following Friday, he was playing a solo onstage at the Opry, standing on his tiptoes and holding his mandolin aloft so the microphone could pick up the notes.

Photo: Marty Stuart

Stuart shot this photograph of Johnny Cash just days before he died in 2003.

For the next two years, he lived in Nashville with Flatt and his wife. “I was too young to drive, so if I wanted to get out, I had to shadow Lester pretty much everywhere he went.” As a college student, Bobby Cudd remembers seeing him with Flatt at a concert in South Carolina. “He looked like the little kid from The Addams Family, playing the hell out of a mandolin.” He may have been little, but he was a teenage apprentice with what he calls “diplomatic status,” fishing and playing poker with Flatt and his buddies Roy Acuff and Ernest Tubb, mingling easily with the stars backstage at the Opry, which then still called the Ryman Auditorium home. “Walking into the Ryman with Lester Flatt was the equivalent of walking into the Vatican with the pope,” Stuart says.It was not long after Flatt died, in 1979, that Stuart got the call from the Man in Black. He toured with Cash for five years, during which time he married Cash’s daughter Cindy (whom he later divorced) and played on the Class of ’55 album (which also featured Carl Perkins, Roy Orbison, and Jerry Lee Lewis). In the late eighties and nineties, Stuart went on to a successful solo career (hits included “Hillbilly Rock,” “Tempted,” and the Travis Tritt duet “The Whiskey Ain’t Workin’”), but he retained a lifelong friendship with Cash, and he and Smith still live in the house he bought next door to “J.R.” and June. On the same day he and Cash finished “Hangman,” Stuart took the now iconic portrait that graces the cover of his second book of photography, Country Music: The Masters.

Photo: Marty Stuart

Bill Monroe.

The photos in that book, as well as the trove stored in his warehouse/office just outside of Nashville in Hendersonville, are all part of Stuart’s crusade to save the Culture of Country, and he’s in a singular position to do it. Adopted into the “family” by its elders at such an early age, he was not just a prodigious talent, he had the remarkable wherewithal to realize he was watching what he calls “history in motion.” So just a year into it, long before he started collecting “the family jewels,” he began to document that history. At thirteen, on his first trip to New York, he discovered the photographs the legendary jazz bassist Milt Hinton had taken of such fellow performers as Billie Holiday and Miles Davis. Struck by the intimate, behind-the-scenes quality of Hinton’s work, he realized he had the same access. Stuart called his mother, Hilda, herself an amateur photographer, and she sent him a Kodak Instamatic. Just like that, he became what Susan Edwards, executive director of Nashville’s Frist Center for the Visual Arts, calls the “memory keeper.”

Photo: David McClister

All the Right Notes

Stuart has been photographing the country music greats since his mother gave him a Kodak Instamatic when he was thirteen.

A Renaissance man but never a dilettante, he infuses his music, his collections, and his photography with equal passion and seriousness of purpose—and more than a little poetry. Bradley Sumrall, chief curator at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, says Stuart’s almost “lyrical approach” with the camera “comes from a deep well of empathy, democracy, interest, and respect.” It’s also contagious. He genuinely wants other people to see into the soul of the music and its faces—and, in turn, the soul of the region and the nation—in the same way that he has been able to.

When I first met him in the mid-1990s, in the course of doing some research for a Vogue country music story that never got off the ground, he implored me to visit Irene Smith, Hank Williams’s sister. There had been a rift in the family and Stuart was pretty much keeping Smith alive, checking in with her in her small Dallas apartment and overpaying her for memorabilia she knew would be in the best possible hands. He drove me crazy until I got on a plane and spent the day listening to story after story of her days on the road with her brother. When she had a heart attack just a few weeks later, he invited me to accompany him to her funeral in Montgomery, Alabama, along with the last of the Drifting Cowboys and Connie Smith, who sang “Amazing Grace” a cappella at the graveside. It was a spine-tingling moment and a piece of history and it didn’t matter one whit to him whether it ended up in print or not.

Photo: David McClister

Country Roots

Stuart in his Hendersonville home, which was once owned by Roy Orbison and is next door to Johnny Cash’s former residence.

That’s because it’s always been about the mission—a mission Stuart tells me has “gotten wider and deeper” since the Superlatives have been together. “Country music as a genre, as an art form, is just as valid out there in the pantheon of the arts as classical, jazz, ballet, whatever,” he says. “Our treasures, our guitars and manuscripts, our costumes, are just as important as Dorothy’s red shoes, or any other artifact in the Smithsonian…. It’s unthinkable to me that Merle Haggard would ever be disregarded. But it happens. My point is that we need to move the whole story forward, not just segments, or the latest, greatest flavor of the month. Save the treasures of the whole story, revere the people of the whole story.”

With the Superlatives, Stuart is also intent on preserving and moving forward the music itself. The band was born in 2000, when Stuart tried out a sabbatical of sorts. Tired of “chasing two-and-a-half-minute hits up and down Music Row,” he was also tired, period: “I hadn’t had a year off since I was thirteen.” But not working turned out to be “just awful,” so he rounded up three other like-minded—and highly regarded—musicians and made an energized return to the sounds he’d been reared on. “Handsome” Harry Stinson, a drummer who honed his skills with everyone from the pop group America to Dottie West and Etta James, was a charter member along with “Cuz’n” Kenny Vaughan, a famed session guitarist whom Stuart first spotted on Austin City Limits with Lucinda Williams. “Apostle” Paul Martin, a producer who plays no fewer than five instruments, replaced the original bass player seven years ago, and now the group is on the road together at least eighty days of the year.

“I knew from the first that it was the band of a lifetime,” Stuart says. They figured out their stunningly tight harmonies by singing gospel—Stuart says the band’s second CD, Souls’ Chapel, on which he plays his late friend Pops Staples’s guitar, was made to “shine a light” on the Mississippi Delta gospel music he loved in his youth. They’ve done bluegrass (Live at the Ryman), Native American ballads (Badlands), and, with their new two-CD recording, Saturday Night/Sunday Morning, they showcase traditional country and twangy Telecaster honky-tonk followed by some equally rocking gospel, just like in real life.

While Stinson points out that the band has its practical aspects—“we’re all at the age where we’re not part of the commercial scene anymore, so there’s a necessity for reinvention”—he also says it’s been an enormous gift. “It’s great to play the kind of music Marty’s into and show how it still fits. The band is a place where we can go to a deeper well.” Like Stuart, he feels like he’s “in rarefied air” when they play with the likes of Haggard and Nelson. “Most people only know the Wikipedia versions of these guys. We’ve become students and teachers at the same time.”

In Fort Worth, they play a terrific song from the new album called “Life’s Little Ups and Downs,” by Margaret Ann Rich, the wife of the late, legendary Memphis country singer Charlie Rich. “Connie turned me on to it,” Stuart tells me later. “I couldn’t believe I’d never heard it, Mr. Country Music Know-It-All.” At more than one point, Stinson comes out from behind the drum set with his “little marching drum,” and the foursome stands close on classic tunes like Jimmie Rodgers’s “Hobo’s Meditation.” Stuart says they mix it up every night, but toward the end of each set the Superlatives leave Stuart at center stage for his mandolin solo. Dressed, as always, in a long jacket, his skinny legs sheathed in leather, he is the new man in all black, his spiky silver hair creating a halo around his soulful face, his eyes closed in deep concentration.

On this particular night, he’s like a man possessed, his fingers flying—at one point he hits so many high notes, more than a few people in the audience let out a scream. But he keeps at it for long minutes, building up, winding down, going, going, bending into it, nodding his head, tapping his foot, until finally he stamps the same foot and it’s over. When the crowd rises for a lengthy ovation, it’s impossible not to think about the thirteen-year-old boy holding his instrument high in order to be heard.

In the lobby, while the band signs CDs and LPs (put out by Stuart’s own Superlatone label), most folks in the long line say they came primarily to see Stuart rather than Haggard. In the last seven years the band’s popularity has been aided by its weekly show on RFD-TV, an idea hatched after Stuart caught a snippet of the old Porter Wagoner Show on the bus television one day. “I thought I was watching a DVD one of the guys put in, but it was a rerun on the RFD network. I thought, ‘I gotta go meet these people; they need a fresh batch.’ Now, seven seasons and a hundred and fifty-six episodes later, we put traditional country and Saturday night back together.”

Photo: David McClister

A Nudie suit worn by Hank Snow hangs among the thousands in Stuart's collection.

Fearful of getting stale, Stuart says he and the band will most likely not return for an eighth season, but they have plenty of other places to go. In the past year, they’ve appeared everywhere from Lincoln Center to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the Smithsonian and were invited to be among David Letterman’s last guests before he departs. In the Bass Hall lobby, a man who discovered the group in Central Park last summer tells me he’s seen them in eight venues since. A retired lawyer, he was out for a morning run when he heard gospel strains coming from what turned out to be the Mississippi Picnic, an annual event that draws thousands. “You don’t hear gospel played in the park every day, so I just drifted over,” he says. “I’ve never seen a presence like those four guys. I’ve turned so many people on to them and they always say the same thing: ‘I didn’t know that’s what country sounded like.’ They didn’t know they liked country until they heard Marty.”

A few years ago, Stuart and Smith built a house in the country near his Mississippi hometown and have plans to create a cultural center nearby that will house much of his collection. Already, it’s made the rounds of museums across the country, including the Autry National Center of the American West in Los Angeles and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. At the Ogden, where Sumrall displayed the suits and other items in a way that informed the photographs and vice versa, Stuart emerged from his bus (in which he’d spent the night on the street out front) to view the progress of the installation. “He was pleased with the placement, but he had one big problem, Johnny Cash’s suit,” Sumrall says. “He said, ‘You need to pull down the waist. Johnny was all waist, and those pants are too high. Also, open the bottom button of his vest. He never buttoned the bottom.’” Memory keeper, indeed.