Arts & Culture

The Tenth Annual Made in the South Awards

And the winners are…

Our tenth annual Made in the South Awards drew hundreds of entries from potters, bakers, distillers, woodworkers, milliners, jewelers, glassblowers, and more, proving once again that Southern craftsmanship and ingenuity is alive and well. Our expert judges joined editors in the office to pore over the entries, selecting a winner and two runners-up in each of our six categories—food, drink, crafts, home, style, and outdoors—and we crowned one overall winner who will receive a $10,000 prize. Among the honorees: a Lowcountry seafood spice mix built on generations of Gullah Geechee family tradition, heirloom-quality fireplace tools hand-forged in Georgia, and a silky barrel-aged chicory liqueur from Mississippi. Special congratulations to this year’s overall winner: Covered in Cotton, run by the husband-and-wife team of Ty and Tracy Woodard. Tapping into the textile know-how of manufacturers in the Carolinas, the company produces gorgeous, cloud-soft blankets from the cotton the Woodards grow on their Darlington, South Carolina, farm.

Overall Winner

Covered in Cotton

Throw blankets; $80-$90

Florence, South Carolina

coveredincotton.com

To Tracy Woodard, every bite of food and scrap of fabric has a story to tell. “People should know where the food they’re putting in their bodies and the fibers they have in their homes come from,” Woodard says. For years, she and her husband, Ty, had been brainstorming ways to use the four-thousand-acre farm in Darlington, South Carolina, that Ty’s family has operated since 1962, hoping not only to keep raising row crops and Black Angus beef cattle, but also to create a product that pays homage to the agriculture and textile industries of South and North Carolina. One morning in December 2017, Woodard awoke from a dream with the answer: simple blankets elegantly woven out of their highest-quality upland cotton.

Inconveniently, this dream came just after Woodard Farms had sold all of its crop for the year, resulting in the buyback of five thousand pounds of raw cotton. What the company lacked in timing, though, it made up for in location. “We’re so fortunate that there is such a strong remnant of the textile industry in our area,” Woodard says. “It looks a lot different than it has in decades past, but we found some incredible local businesses that understood our vision and jumped on board.”

Each of these Carolina companies lies within 150 miles of the Darlington farm. After the Woodards harvest the cotton, the crop travels some twenty miles west to S P Coker Cotton Gin in Hartsville. “They give us all the data for that cotton, so we can trace every bale to the field it was actually grown on,” Woodard says. “We know the exact plot of land each blanket came from.” From there, the ginned cotton jumps the state line to Thomasville, North Carolina, where Hill Spinning ring-spins the yarn before Shuford Mills in Hickory plies it. Back in the Palmetto State, in Blacksburg, Weavetec Inc. produces the throws on Jacquard looms and sends them to Craig Industries in Lamar, where the blankets receive hand-sewn Covered in Cotton labels. Back at their home in Florence, Tracy and Ty package and ship the finished blankets to buyers across the country. “It’s about a five-hundred-mile round trip that the cotton makes before it returns to us,” Woodard says.

The three initial styles, which Woodard designed with Harold Pennington Jr. at Weavetec, take their names from her and Ty’s three children: the Tate, the original basket-weave throw named for their oldest; the Tyson, a waffle-patterned baby blanket named after their only daughter; and the Tobin, a herringbone design whose namesake also inspired Covered in Cotton’s philanthropic mission.

Photo: brennan wesley

Ty and Tracy Woodard on their family farm in Darlington, South Carolina.

In 2015, three months after he was born, Tobin Woodard spent thirty-five days at Palmetto Health Children’s Hospital in Columbia with severe bacterial meningitis, undergoing an emergency brain surgery from which doctors warned he might never fully recover. While the family sat in a cold hospital room before the operation, a nurse handed them a blanket to keep them warm, and the practical gift comforted the family immeasurably. Now, for every ten throws Covered in Cotton sells, it donates one to a South Carolina children’s hospital.

“After that time, what was important was important, and what wasn’t, wasn’t,” Woodard says. “Tobin just turned four, and he is completely healed and whole in every way. There is hope to share with other people going through that.” Since last December, Covered in Cotton has donated ninety blankets to families with children in hospitals in Columbia, Florence, and Charleston, and this fall, they added Greenville.

The company also has new offerings, including another throw, named for Ty’s grandmother; a line of swaddle-style baby blankets; and six dish towels screen printed with recipes from various family matriarchs. These latest products, of course, remain rooted in Carolina agriculture and manufacturing. “Today more and more people are generations removed from the farm,” Woodard says. “We want to educate people about where it all comes from. It’s a privilege to share this story.” —Caroline Sanders

CRAFTS

CATEGORY RUNNERS-UP

Sunhouse Craft

Hand brooms

Berea, Kentucky

$5–$95; sunhousecraft.com

Seven years ago, Cynthia Main left the shop she ran in Chicago, where she repurposed salvaged building materials, to study barrel making at a farming skills school in Michigan. There, she impulsively opted in to a broom-making class. “It’s a craft that just gets into you,” she says. “I was fried on big machine production. I feel like this is a way to rehumanize the process.” After relocating to Berea, Kentucky, last year, Main took up broom making full time. Now she sources broomcorn from Texas, leather from Thoroughbred Leather out of nearby Louisville, and wood from the downed sticks and branches around her home, all of which she saws, shaves, and shapes into rustically imaginative brooms, brushes, and dustpans in her studio. “A craft like this stands at the nexus of place and people,” Main says. “It’s people using what grows on the land to give them what they need.”

David Rinella

Craig Proper

Dinnerware

Tulsa, Oklahoma

$5–$95; craigproper.com

The key to Taylor Dickerson’s pottery is near perfection. “I want to create things that make people wonder whether they’re handmade or not,” says the twenty-eight-year-old Oklahoma potter, who in 2016 opened Craig Proper (his middle name combined with the design aesthetic he strives toward). His hand-thrown, -glazed, and -fired goods are almost exact copies of one another, a process he refined during the six months of forty-hour workweeks he put in practicing the craft before selling his first piece. “I wanted to get all of my failures out,” Dickerson says. “Now I spend a lot of time weighing out the clay to make sure things are exact. Everything I make is something I’d want to use in my own house.” His bowls, plates, tumblers, and mugs come in an array of muted pastels to ensure the pottery remains as timeless as it is—nearly—flawless.

Drink Category

CATEGORY WINNER

Cathead Distillery

Hoodoo Chicory Liqueur

Jackson, Mississippi

$35; catheaddistillery.com

Photo: David Rinella

The flavor of Hoodoo Chicory Liqueur Legba Reserve is familiar yet not. On first sip, it comes off like a cousin of a coffee liqueur. But it’s more high-spirited, with bright citrus notes up front and fleetingly bitter toffee notes on the finish—an entrancing combination.

“My parents drank coffee with chicory when I was growing up,” says Cathead’s master distiller, Phillip Ladner. He chased after that taste by infusing ground chicory root into Cathead’s mainstay spirit, the vodka the company has distilled since 2010. The first batch failed to flourish into anything very interesting after a week or two, so the cask was set aside and forgotten. Some months later, distillery founders Richard Patrick and Austin Evans inquired about it, and Ladner tracked it down. By then, the infusion had matured into something exciting. (The first tasting note involved “holy” and a sharper word for “dung.”) More experimentation followed, including the use of bourbon barrels for aging. They sent the liqueur to market and tweaked it again based on feedback from bartenders—more chicory content, a bit sweeter.

The final silky, full-bodied potion possesses enigmatic shadows, the perfect profile for a drink named after Afro-Caribbean mysticism. (Ladner barreled the first batch under a full moon on a Friday the thirteenth, a circumstance he regrets being unable to replicate.) The liqueur also rings in at 66.6 proof—evidence of more occult playfulness. “One of our wholesale partners asked us to change the proof,” Patrick says. “We said no. It’s fun and it’s dark, and it’s what the product is about.” —Wayne Curtis

DRINK

CATEGORY RUNNERS-UP

David Rinella

Reservoir Distillery

Hunter & Scott bourbon whiskey

Richmond, Virginia

$40; reservoirdistillery.com

A decade ago Dave Cuttino and Jay Carpenter “both had jobs selling things people really didn’t want,” Cuttino says. A better plan, they thought, was to make something people actually sought out—like whiskey. So they founded Reservoir Distillery in Richmond in 2008, putting them among the first wave of craft distillers to produce bourbon outside Kentucky. They launched by distilling three single-grain flagship products—whiskeys from corn, rye, and wheat. A few years later, while looking for a blend that would offer more complexity and authority, they combined the trio. A young bourbon with a mature taste emerged, and they christened it Hunter & Scott, a nod to their middle names. Their goal was to bottle a bit of Virginia. “We source all the grain from within about forty miles and use Virginia wood for some of the casks,” Cuttino says. “Provenance is everything.”

David Rinella

Creature Comforts Brewing Co.

Reclaimed Rye

Athens, Georgia

$10 per six-pack; creaturecomfortsbeer.com

When the brewers at Creature Comforts Brewing Co. in Athens, Georgia, set about devising beers that drinkers would welcome in winter as much as in summer, they took a long look at amber beer. “It’s not one of the most exciting styles,” admits David Stein, a cofounder and vice president of brand development and innovation, “but it’s one of the more traditional.” Stein and his partners endeavored to imbue the ale with a bit more character. “When we were thinking about this beer, we thought about whiskey, and how we could deconstruct a rye whiskey and turn it into a lower-alcohol brew.” They used malted and unmalted rye, and then aged the beer on different types of wood in search of something that could lend a dry touch and intricacy. They settled on French oak, less overpowering than American oak. The finished beer tastes light and full of body—a welcome sight in the fridge no matter the season.

HOME CATEGORY

CATEGORY WINNER

Southern Andiron & Tool Co.

Fire tools; $495–$1,250

Brookhaven, Georgia

southernandiron.com

Photo: David Rinella

“I’m a fireplace nerd,” says Trey Miller, who with his wife, Marjorie, founded Southern Andiron & Tool Co. in an Atlanta suburb. Fascinated with the role of the fireplace throughout human history, Miller buried himself in study, focusing on antique tools. Inspiration sparked when friends began calling on his expertise to help them outfit their homes and fireplaces with the right wood and proper implements. He imagined a business plan centered around the practice—refurbishing antique andirons, which keep fireplaces clean and help wood burn more efficiently; redesigning lightweight fire screens; and creating bespoke fire tools that were not only functional but of heirloom quality.

After two years of research and material sourcing, the Millers’ idea kindled into handsome goods that include a heavy-duty fire iron, an ash trowel, and an ash whisk, all of which originate at a manufacturer in Doraville, where Georgia-forged raw steel meets hardwood handles. Miller and his team then hand sew thick leather around each handle as a heat protectant and install wooden whisk heads with a natural Tampico bristle. “Our tools are built to last for generations,” he says. “The fireplace doesn’t need to be reinvented. We just want to help people get excited about fires again. The tools are really a means to that end.”

—Caroline Sanders

HOME

CATEGORY RUNNERS-UP

David Rinella

Nate Cotterman Glass

Flow decanters

Penland, North Carolina

$170; natecotterman.com

When Nate Cotterman realized how many out-of-class hours his glassblowing elective required during his second year of college, he tried to drop the class. Fortunately, it was too late. “Glassblowing took to me, and I really took to it,” he says. Now Cotterman works out of a studio in Penland, where he secured a three-year residency at Penland School of Craft, to produce his one-of-a-kind glass goods, including seven styles of decanters. “I started with eighteen, but I realized most weren’t functional,” he says. “They were too heavy, or didn’t pour well, or had too big or small of a footprint to use.” The winning looks blend performance with modern aesthetics—tilts, curves, askew angles—and pure glassblowing technique. “For me, glassblowing lends itself to having a clean, untouched look,” Cotterman says. “I’m using heat, gravity, and centrifugal force to get glass to do what I want instead of forcing it. It’s engaging to work with this hot, fluid thing, and freeze it in time.”

David Rinella

LiBird Studio

Magnolia faux bois candlesticks

New Orleans, Louisiana

$495; libirdstudio.com

Sculpted carefully out of low-fire clay in her New Orleans studio, each of Lisa Alpaugh’s faux bois candlesticks has its own personality. “My magnolia designs are more traditional,” Alpaugh says. “My other flowers often feel like a dancing girl with wild hair.” Those floral themes often result in top-heavy candlesticks, and discovering how to shape them out of solid, wet clay required a long, strenuous period of experimentation. Today she builds each of her singular pieces from the bottom up, bisque-fires it, dips it in a hand-mixed white glaze, and fires it once more. The candlesticks come with Alpaugh’s favorite Vance Kitira candles, as well as fitters for stability. “I love to set a pretty table,” she says. “I love antique silver, and I collect antique monogrammed linens. This adds something lighthearted to the arrangement.”

Food Category

CATEGORY WINNER

Taste of Satira

Gullah Geechee crab boil sack; $15

Cross, South Carolina

tasteofsatira.com

Photo: David Rinella

“I’m not a classically trained chef—I’m a home cook and proud of it,” says Pamela D. Jones Mack, the founder of Taste of Satira. “I cook with heart. And I love sharing the Gullah Geechee cuisine.” Jones Mack became a food entrepreneur the old-fashioned way—by necessity. Growing up not far from Charleston, South Carolina, she was the oldest of four sisters. When her parents both took on night shifts, she began cooking for her siblings, making dishes she had watched her grandmother and great-grandmother prepare.

After college she moved to Atlanta, where she and her friends met up on Sundays to make meals together. Her friends started asking her why she didn’t cook professionally. Jones Mack waved them off, but then an encounter with the creator of an underground supper club led to her preparing a well-received meal there. A catering side business soon blossomed. Recalling the bold flavors of her childhood, she concocted spice blends for her meals and soon started selling her mixes in jars to those who inquired. For her boil spices—a mix of ten ingredients—she opted to “up the ante” with more cayenne to enable the shrimp, crab, or crawfish to speak with more force. She packed the spices in a cheesecloth bag to be dropped into a boil (it’ll season four to five pounds of shrimp), but she says the more adventurous could use it for blackened fish or for bringing heat to other dishes. “It depends on your palate.”

This fall, Jones Mack got married and moved home, bringing her Gullah Geechee catering business with her. “That’s the reason I’m moving back to South Carolina,” she says. “It’s being said that the Gullah Geechee culture is disappearing, and I want to be a part of preserving it.” —Wayne Curtis

FOOD

CATEGORY RUNNERS-UP

David Rinella

Dayspring Dairy

True Ewe Bourbon Caramel

Gallant, Alabama

$8–$14; dayspringdairy.com

“We started about eight years ago—I guess it was one of those midlife crises,” Greg Kelly says. “Midlife adjustment,” corrects Ana, his wife and business partner. That adjustment involved Greg quitting his IT job in 2010 and the couple building Dayspring Dairy on thirty acres in Gallant, Alabama, establishing the first sheep dairy in the state. They started out with a dozen sheep for cheese making, and then began thinking about what else they could produce. “I’m half Colombian, and in South America, dulce de leche is just part of the culture,” Ana says. The couple started experimenting, mixing sheep’s milk with raw turbinado sugar and cooking it down until it developed an inviting, deep caramel taste. The ensuing sauce comes in three flavors: vanilla bean, coffee, and bourbon. We’re partial to the bourbon version, which is particularly superb over ice cream (and equally righteous right out of the jar).

David Rinella

Scratch Pasta Co.

Virginia Wheat Campanelle

Lynchburg, Virginia

$7 per 12-oz. bag; scratchpastaco.com

When chef and entrepreneur Stephanie Fees began selling her pasta at the Lynchburg, Virginia, farmers’ market three years ago, she made it by drying it in a small greenhouse rigged with fans, heaters, and humidifiers, checking the progress every hour. “Pasta cracks if it gets too dry,” she says. “It was a very labor-intensive process for the first couple of months—but I learned a lot about the science of pasta.” She’s since upgraded to a commercial dryer and a pasta machine, but she’s kept with other traditions—including buying winter wheat from a Virginia farmer and using a bronze extruder to give the pasta a “rough, artisan texture.” That’s especially evident in the Virginia wheat campanelle, which holds on to even thick sauces with an enviable tenaciousness. Fees also dries the pasta now over fourteen hours, rather than using a quick blast of heat as larger producers do. “It preserves more of the true nature of the wheat.”

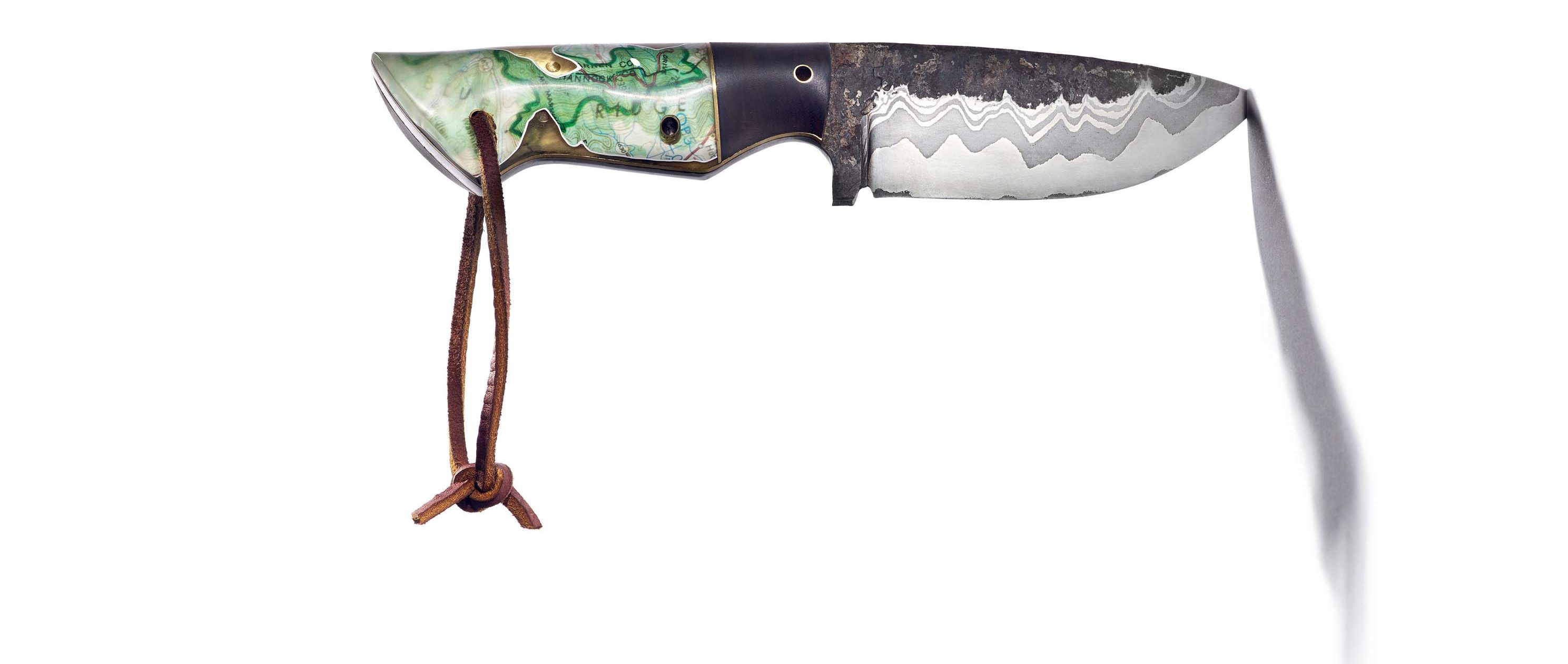

Outdoors Category

CATEGORY WINNER

Stono Knife Works

Blue Ridge Camp Knife; $325

Taylors, South Carolina

stonoknifeworks.com

Photo: David Rinella

Bladesmith Alec Meier literally dreamed of this knife. While visiting his parents in Franklin, North Carolina, he glimpsed a three-dimensional topographic map his father had given him when he was a child. That night, his sleeping brain conjured the image of a knife with a handle crafted from a sliver of that old map, set in clear resin, so you could see the peaks and hollows of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Meier had long been obsessed with knives and swords. As a boy he made knives “the old-fashioned way,” he says, “on a coal forge with hand bellows.” As a historic preservation student at the College of Charleston, he became enamored with the practice of repurposing materials from old Southern houses. He forms the Damascus in his Blue Ridge Camp Knife from twenty-seven layers of steel from old files and saw blades, grinding the four-and-a-half-inch blade to thin the steel at the edge for effortless slicing and carving. But the dreamed-up handle, with its bit of topographic map sealed in resin just as Meier envisioned, is the real showpiece. If the Blue Ridge Mountains aren’t your outdoor playground of choice, don’t worry; Meier is happy to customize the handles based on a client’s request—from Charleston to Arizona to the surface of the moon. —T. Edward Nickens

OUTDOORS

CATEGORY RUNNERS-UP

David Rinella

R.H. Jensen Game Calls

Duck calls

Wilmington, North Carolina

$250–$700; rhjensengamecalls.com

“I like stuff with a story,” Ralph Jensen says of the duck calls he turns, carves, and tunes by hand in Wilmington from a wide array of heritage woods, such as old walnut harvested from a Pennsylvania pond and ancient longleaf pine from logs salvaged from the bottom of the Cape Fear River. The custom woodworker has even made calls from a thirteenth-century chapel door from Bath, England. Jensen likes adding to the story, too—he will carve images of dogs and ducks into calls, and he’s often asked to re-create the likeness of a favorite hunting companion on the large barrels that serve as canvases. One customer even asked him to incorporate the ashes of the buyer’s beloved retriever. After carving and painting, Jensen says, he mixed a bit of the ash into the final finish, then painted it over the retriever’s hand-carved relief. “The buyer was taken aback by it, and so was I,” Jensen says. “It underscores how intimate and personal a duck call can be.”

David Rinella

Goldens’ Cast Iron

20.5-inch Kamado-style Cooker and Table Cart

Columbus, Georgia

$1,700; goldenscastiron.com

Established in 1882, Goldens’ Cast Iron casts subway brake components, truck parts, bridge anchors, and gear housings, as well as these cast-iron kamado-style cookers. The beast of a grill/smoker/wood-fired oven gets clad in an all-weather powder-coat finish, weighs 330 pounds, and comes with height-adjustable grates, a searing plate, a single-piece cast-iron firebox, and a stainless-steel thermometer. A hinge cast into the cooker and a heavy-duty spring make for easy opening. “Southern pride and craftsmanship are intrinsic parts of our identity,” says George Boyd Jr., who along with his brothers, Ed and John, is the fifth generation of his family to work at Goldens’. A few years ago, the company was exploring new ideas when an employee complained he’d broken the top of his ceramic cooker. “A light bulb went off,” Boyd says. If Goldens’ could help stop a train, it could also make the last cooker a customer would ever have to buy.

Style Category

CATEGORY WINNER

Blue Delta

Custom pants; $500–$600

Tupelo, Mississippi

bluedeltajeans.com

Taking a Savile Row approach to an American wardrobe classic, the design team at Blue Delta creates its denim or stretch cotton pants by making a personal pattern for each client, using sixteen exacting measurements. Once your pattern is filed, you choose the pants’ cut, fit, fabric, and thread. This bespoke service—which has made Blue Delta popular with traditionally hard-to-fit folks such as professional athletes, including Dak Prescott and Eli Manning—takes four to six weeks to complete, and the resulting pants will endure for years.

Cofounders Josh West and Nick Weaver put in lots of early mornings and late nights to get Blue Delta up and running, but the Mississippi natives don’t mind admitting that luck played a part in their success. Finding a lead seamstress with a denim background was especially fortuitous. “Sara Richey actually sewed for the only independent contractor of Levi’s 501 jeans,” Weaver says, and she lost that job when the local garment industry fled overseas. “Hiring her brought a lot of years of experience to a young company.” And while Blue Delta makes “a damn good jean,” he says, another fortunate meeting—this time at one of the company’s roaming pop-up shops, with the head of London’s storied fabric house Holland & Sherry—led to the development of Blue Delta’s dressier pant. Made with lightweight H&S Italian stretch cotton, the soft pants come in thirteen colors. “Seventy percent of our clients own more than one pair,” Weaver says. —Elizabeth Hutchison Hicklin

STYLE

CATEGORY RUNNERS-UP

David Rinella

Oil / Lumber

Haori Coat

Nashville, Tennessee

$175; oilandlumber.com

American work wear meets classic Japanese design in Oil / Lumber’s largely unisex jackets, pants, shorts, and pullovers. “When I started Oil / Lumber, I was designing more along work-wear lines,” says the company’s founder, Ethan Summers. “Then I started to think: What’s the stuff that made me weird and different as a kid that I love now?” He found the answer in his childhood closet among the traditional Japanese clothing his mother made for him when he was a boy. Summers took three years to perfect this contemporary take on the samurai-style haori coat, now one of his most popular garments. The light jacket is made to order in the company’s Nashville studio and comes in black, natural, earth, and indigo, the last of which is hand dyed in the Japanese shibori style, using Tennessee-grown indigo. “Each dye batch is a little different,” Summers says. “But I think that’s why people like the indigo version so much—because each jacket has its own identity.”

David Rinella

Saint Virginia Handcrafted Textiles

Big Square Scarf

Gainesville, Virginia

$128; saintvirginia.com

Amy Hindman fell in love in Paris—with scarves. “I was sixteen and there was a French girl who had on this amazing scarf,” she says. “It was my first fashion moment.” Nineteen years later, when her hair began falling out during breast cancer treatments, the accessory took on new meaning. “I’d just had a baby, and I went from feeling feminine and beautiful to bald and sick,” Hindman says. “I wanted an amazing scarf, something organic and soft that wouldn’t slip.” With the help of a grant from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and a workshop at North Carolina’s Penland School of Craft, she began her own line: Saint Virginia. Today Hindman hand dyes organic voile scarves with all-natural dyes made from flowers, plants, roots, and leaves, much of which she harvests from the pesticide-free gardens and farms of friends and family. “To make something lasting out of something as fleeting as a rose or wild goldenrod is pure magic,” she says.

Photo: fernando vicente

Meet the Judges

From left:

Erin and Ben Napier

Crafts

Thanks to Erin and Ben Napier, Laurel, Mississippi, is enjoying a boom of sorts. There, the couple founded Laurel Mercantile Co., on Front Street, to design and sell heirloom-quality goods such as kitchenware, comforters, and coffee mugs; and Scotsman Co., where Ben handcrafts one-of-a-kind home furnishings. In 2017, their HGTV series, Home Town, premiered, giving the Napiers the chance to restore historic houses throughout Laurel. “Southerners take the modest things they have and make them beautiful,” Erin says.

Dara Caponigro

Home

“A human touch in a home is so important, especially in our technological society,” says Dara Caponigro, the creative director at F. Schumacher & Co. Before overseeing the company’s inventive fabrics and wallpaper, she worked as editor in chief of Veranda, a founding editor of Domino, design and decoration director at Elle Decor, and decorating director at House Beautiful. Naturally, she has filled her New York home with antiques and handmade goods. “Handcrafted items bring so much personality and depth,” she says. “It’s about soul.”

Rob Samuels

Drink

For eight generations, Rob Samuels’s family has been distilling Maker’s Mark bourbon in Loretto, Kentucky. And although he has acted as Maker’s chief operating officer since 2010, over the years Samuels has been involved in nearly every aspect of the company, including the hand dipping of each bottle in its signature red wax, a tradition his grandmother Margie (a Kentucky Bourbon Hall of Famer) started. “Drinks are such an important part of the culture of this region,” he says. “It’s about what’s in the bottle as well as the story it tells.”

Carla Hall

Food

“Southern food is magical,” says the chef Carla Hall. “When I taste something, it’s like I know the person who made it without ever having met them.” Born in Nashville, Hall rose to culinary stardom on television—including as a contestant on Top Chef and as a cohost of the Emmy-winning talk show The Chew—but keeps her heart rooted in Southern dishes. Her three cookbooks venerate classic comfort foods such as okra, johnnycakes, and biscuits. “Eating this food is the same thing I feel when I go down South,” Hall says. “I’m at home.”

Laura Vinroot Poole

Style

“In the South, we’ve always been innovators,” says Laura Vinroot Poole. That’s certainly true in her case. Over the past two decades, Poole has established herself as one of the region’s leading tastemakers, founding Capitol, a luxury clothing boutique in Charlotte that touts emerging designers as well as venerable brands that create eye-catching women’s designs, and then spawning two sibling stores in the Queen City: Tabor and Poole Shop. Last spring, she spread westward, opening Capitol’s second location in Santa Monica, California.

T. Edward Nickens

Outdoors

Whether he’s fly fishing for rainbow trout in East Tennessee, flushing bobwhites in Georgia’s Red Hills, or relaxing at home in Raleigh, Garden & Gun contributing editor T. Edward Nickens is always on the lookout for innovative outdoor goods that tell a story. “I’m intrigued when a maker goes a few extra steps to connect their work to the Southern experience or landscape in some way,” he says. This marks the ninth time that Nickens, whose books include The Total Outdoorsman Manual, has judged the Made in the South Awards’ Outdoors category.

Interested in Entering Next Year’s Awards?

We’ll start accepting nominations for the 2020 Made in the South Awards early next year. If you’d like to be notified when the nomination period opens, please send an email to mis@gardenandgun.com.