Food & Drink

The Big Heart of Ashley Christensen

Though the toast of Raleigh is one of the hottest—and busiest—chefs in the South, it’s her work outside the kitchen that continues to define her

Photo: Peter Yang

Chef Ashley Christensen, who is thirty-six, has a unicorn app on her smartphone. “Check this out,” she says gleefully, flipping through photos of America’s celebrated cooks and sommeliers now adorned with spiraled horns and puffy wings amid backgrounds of heart-shaped balloons. Such impish playfulness is not what one expects of badass, empire-building chefs like Christensen, or chefs generally, as even casual viewers of cuisine competitions can attest. Chefs, like other artists, have temperaments. Egos that drive and consume and lead to fits of perfectionism or worse. They tip into caricature. They forget the food. They start worrying about their hair.

Not so Christensen, who, though she has faultlessly lovely hair, avoids narcissism like dysentery. Instead, she concerns herself almost exclusively with enjoying life, doing good, and enabling others to do the same. That she achieves this primarily through her cooking is gravy for us all.

Self-taught and the humbler for it, Christensen specializes in tweaking comfortable classics into something finer, as if sewing a sweatshirt from cashmere. She never condescends or preens. Nor does her food, which hits that perfect note of being better than seems possible without making you feel like an aristocratic prig for eating it. Her Raleigh, North Carolina, restaurants are the renowned Poole’s Downtown Diner, which is anything but; Chuck’s, a single-concept burger joint serving homemade shakes thick enough for Newt Gingrich to walk across; Beasley’s Chicken + Honey, a yard bird haven with biscuits so rich they make you feel dirty; and the Fox Liquor Bar, named after her father, a man of many passions, much like his daughter. Christensen opened all of these establishments in downtown Raleigh, which not long ago was so desolate tumbleweeds found it dull, because she believed in urban revitalization and that if she built it they would come.

Photo: Peter Yang

Plate of Goodness

The mac and cheese at Poole’s Diner.

Come they did. (The mac and cheese at Poole’s alone caused an avalanche of desire and longing not seen since Raquel Welch wore that cave girl bikini.) Lines now form on previously empty streets.

“What Ashley brings to the table is always with a greater good in mind,” says local philanthropist Eliza Kraft Olander. “She has a great deal of integrity. She is a rare bird.”

Christensen aims to elevate everything she touches, up to and including her customers, who feel in the moment that, yes, this is what food should taste like—loved, respected, realized. And this exquisite visceral contentment is about nothing so much as it is Christensen, who infuses every dish not just with impeccably balanced flavor but also her decency. If Gregory Peck were a comely blonde chef, he would be Ashley Christensen.

Said decency extends well beyond the kitchen. A zealous fund-raiser, Christensen puts her money where your mouth is, devoting half of her time to charitable causes. Not for her a line of fry pans at Walmart or a storefront in Times Square. “I want to give more than I take,” she says matter-of-factly over drinks at Fox’s, where she is sampling myriad cocktails for an upcoming event.

Christensen waves over the woman delivering the highballs.

“The mint is a good idea,” she says warmly. “But not this particular mint. It’s a little funky.” She swallows another swig. “Maybe rosemary?”

The philanthropic bug bit Christensen in 2003, when the then twenty-six-year-old volunteered for a 330-mile AIDS ride from Raleigh to Washington, D.C. She started with a modest goal of raising $26,000 and ended up collecting a record-breaking $56,000.

Photo: Peter Yang

Caring Arms

Ashley Christensen with a friend.

“On the ride,” she says, “folks would come up to me and thank me. I was completely unprepared for that. People in tears. I was so moved.”

The ride “secured my connection to this city,” she explains. Before then, she’d fantasized about uprooting to New York or San Francisco, locations with more to offer a nascent chef. “But the ride made me think of everything differently. I realized I had influence here.”

Last year that influence (and quite a few unforgettable fund-raising dinners) raised $120,000 for the Frankie Lemmon School and Development Center, a tuition-free facility for developmentally disabled children. Christensen also collected upwards of $70,000 for Stir the Pot (STP), a charity she founded to unite chefs and funnel cash into the documentary arm of the Southern Foodways Alliance (SFA).

“STP events have helped knit together a community,” says the SFA’s director, John T. Edge, author and grand pooh-bah of all things culinarily Southern. “Ashley is introducing line cooks to farmers, citizen diners to historians.” Which is all part of Christensen’s modest plan to remind us of our immutable interconnectivity and our obligation not to act a fool just because modern times indulge it.

Christensen admits she has no tolerance for pettiness (hers or others’) and is perplexed when peers withhold wisdom or adopt ludicrous personas. She has eaten in restaurants where the chef was so aloof he pretended he wasn’t there. And she has found this approach lacking.

“With Stir the Pot, I wanted to unite more chefs in my area,” she explains, taking a long swallow of tequila. “Certain folks were talking s*** about each other. I felt like if we had the opportunity to get on the same side of things, we could work it out, start conversations.”

Her diplomacy succeeded. Now former rivals cook side by side, sharing recipes and advice minus the envy and smack talk.

“In the South, we want to take care of each other. To help each other grow,” says Christensen, who cites chefs such as Charleston’s Sean Brock and Atlanta’s Anne Quatrano as mentors. “Down here, no one is saying, ‘I can’t show you how to make that.’”

It is dinnertime at Poole’s, and Christensen is elucidating the blackboard-only menu, saying she designed it to allow diners to “eat the way chefs like to eat,” which is to say, indecisively and exuberantly. The notion is freedom of choice for the patron and the chef. Gluttony is optional, but hard to resist. The freestyle menu also means you never get weary of the same old selections. To eat at Poole’s is to be in a constant state of high romance, never a marriage.

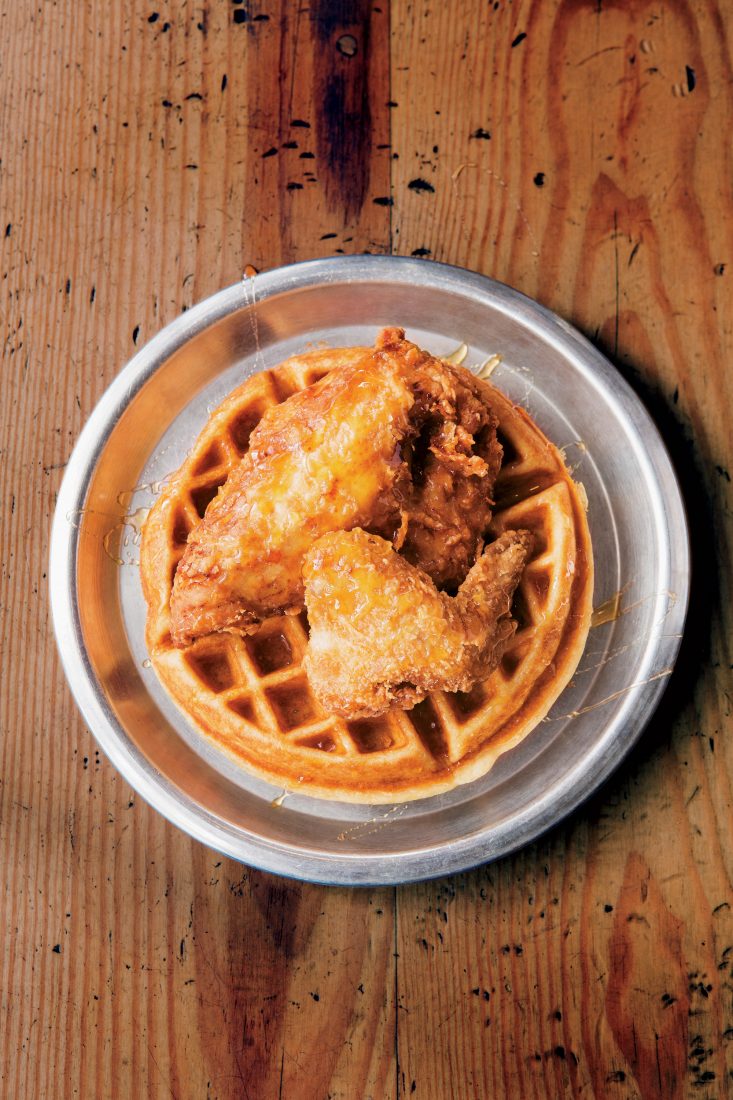

Photo: Peter Yang

Winning Combination

The fried chicken and waffles at Beasley’s Chicken + Honey.

“Southern chefs are less formal,” Christensen says of her approach. “My parents made incredible meals, but none of it was planned.” More to the point, she stresses, “I refuse to be disconnected from where I started.”

By this she means not only Raleigh, where she was a North Carolina State student with an undeclared major before she dropped out to cook full-time, but also her hometown near Greensboro, where she was raised by her parents, Robert and Lynn, avid organic gardeners, and where, family lore has it, little Ashley took her first steps toward a glass of sweet tea.

“Growing up, my understanding was you ate what grew in the Southern earth,” she recalls. “What grows together goes together.”

“Ashley’s cooking is vegetable driven,” observes Edge. “She comes out of the meat-and-three tradition and knows, in her bones, that the three end of that is what really matters.”

In October, Christensen was invited to cook the signature lunch for four hundred guests at the Southern Foodways Alliance barbecue fete in Oxford, Mississippi. With elephantine brass, she chose to go vegetarian for the entire twelve-course meal. She brought the tables to their fatback-loving knees.

“It felt like the best meal we’ve ever cooked,” Christensen recalls, explaining that the choice to eschew animal protein was not about being deliberately contrary, but a gesture of respect to the many pit masters in attendance. It was also a tribute to her personal history, and the history of all Southerners whose memories of barbecue centered not on the food but on the gathering itself.

“I thought it would be really cool to put things in the middle of these forty-five tables where everyone would say, ‘I know that dish but that’s not how we do it.’ I wanted to stimulate dialogue about tradition and stories and do it in a way that no one would notice that the meat never hit the table.”

Her moxie (and her cooking) earned Christensen a four-minute standing ovation. “It was shattering,” she recalls. “When I spoke, I said, ‘What we wanted today more than anything else was for you to look at us the way you are looking at us right now.’”

The meal left diners weeping. Christensen was honored, but not surprised by the waterworks. “It wasn’t about me. It was about what food makes people recall. How it sparks so much.” She likens food to music. (It was Christensen’s intention to enter the music business, but after working as a rep for BMG while still in college and witnessing “the scaly underbelly,” she changed her mind.) For Christensen, music and food don’t lie. They cut to the quick of life, say the things you can’t, conjure sentiments you think you’ve forgotten.

“The way food makes me feel,” Christensen says, her eyes narrowed with delight, “is the one relationship I’ve never doubted.”

When Christensen was in kindergarten, the school called her mother in to talk about her daughter, whom they described as “overly logical for her age,” and perhaps a bit impertinent. Lynn thanked them for their concerns, then reassured Ashley she was going to be just fine. At home, Christensen’s older brother Zak offered another take.

“You know you’re retarded, right?”

Christensen laughs as she shares this story. “I do have ADD. I worry about myself a bit when I get racing, ‘Just get to tomorrow, just get to tomorrow.’ I want to be more appreciative of everything that happens each day.”

No sooner has she said this than she confesses she is about to start writing a cookbook—“maybe more than one book?”—and that she has been mulling over the prospect of a coffee shop. “One with incredible sandwiches. There is really no place to go

and spend eight dollars on a killer smoothie. And I can’t understand why that isn’t happening. Maybe have a sweet wine list…” She trails off.

That is the thing about Christensen. When she notices something missing in the world, she creates it.

It is Monday night and Christensen has invited twenty or so friends over to her house for dinner. Nothing fancy, just boiled prawns with drawn butter, sautéed mushrooms as fat as baby legs, chickens roasted outside over charcoal Christensen made herself in a cut-out barrel her uncle fashioned.

“The neighbors have called the fire department a few times,” she says, nodding toward the barrel’s flames, licking as high as kites toward the night sky. “But then they come, and see what we’re doing, and get excited about the barbecue.”

Around her, guests swirl, snacking on pan-fried fingerling potatoes and sampling a generous array of wines. Taking a break from the stove, Christensen retires to a corner of the living room and surveys the scene.

“I remember that feeling of being a kid at a grown-up party,” she says, eyes lit. “Overhearing folks say to my dad, ‘I don’t like eggplant,’ or ‘I don’t like okra,’ then watching him lean over and pop something in their mouths and they would sit back and sigh and go, ‘That’s amazing!’”

Christensen smiles, cheeks flush.

“When I was younger, I thought what I did was about the food. But what I came to realize was it was about watching people interact with each other when there is a comfort zone created over something shared.”

She looks around her house, brimming with people chatting, laughing, swooning over dishes she has cooked, their faces pink and greasy and satisfied. Soon enough, someone calls from the kitchen. Christensen wastes no time. She is needed there.

>G&G Bonus: Get chef Ashley Christensen’s tips and recipe for fried chicken