Travel

The Call of the Jungle

Photo: Christopher Lamarca

To reach the remote Yachana Lodge, there is the long way, and then there is the longer way. To understand Douglas McMeekin and his mission, it’s wise to choose the latter.

Leaving Quito, the 9,350-foot-high capital of Ecuador, my driver weaves through Pan-American Highway traffic along the spine of the Andes through the Avenue of Volcanoes. We turn and cut switchbacks down the eastern slope to the town of Baños. The next day, we traverse the Pastaza River Valley on a narrow ledge carved out of cliffs by Royal Dutch Shell in the 1930s but only paved within the past decade. Waterfalls as tall as skyscrapers plunge into the gorge, feeding a braid of white-water far below. We wind down, down, glimpsing the unbroken Amazon canopy stretching east. Rivers rage and roadside vegetation presses in like a green insurrection. In the frontier town of Misahuallí, I tuck into a two-dollar plate of chicken and rice at an open-air cucina while two men draped in boa constrictors tout river tours and a monkey cavorts in the plaza. The next morning, we bounce along a washed-out gravel road until we meet the Napo River, Ecuador’s biggest Amazon tributary, where I board a long wooden canoe. This is the end of the road, of all roads here. But it won’t be forever. That truth brought McMeekin to this unlikely destination.

Photo: Christopher Lamarca

Douglas McMeekin standing above the Napo River.

Ever since Texaco struck oil in eastern Ecuador in 1967, the fragile rain forests at the Amazon’s headwaters have been slowly dying. The culprit is less the extraction itself than the network of roads companies build to access the reserves. Roads bring people, and people destroy forests by overhunting, cutting timber, and farming. Ecuador has the highest deforestation rate in Latin America.

McMeekin knows the roads are coming, and so the transplanted Southerner is trying to save the jungle—one person at a time. A resident of Ecuador for nearly thirty years, he runs the Yachana Foundation, whose name means “a place for learning” in the Quechua language. Yachana educates and trains the Amazon’s long-ignored Indians and mestizo colonists. A one-man idea factory, McMeekin has launched dozens of projects—from tilapia farming to jungle chocolate, Amazon beekeeping to women-run banks, an alternative high school to a jungle lodge—all intended to equip people for work that will sustain both them and their forest home. A Quechua or other Indian who earns a meaningful living as a guide or by producing organic chocolate, the thinking goes, is not likely to clear forest for timber or pasture or abandon his family for a job swinging a machete for an oil company. In 1995, McMeekin’s entrepreneurial exuberance and social conscience landed him on the front page of the Wall Street Journal. Over the past decade, the Yachana Lodge he founded has won ecotourism awards from Condé Nast Traveler and the National Geographic Society. In a Spanish-speaking banana republic 2,600 miles from his native Kentucky, McMeekin, who is now seventy, has kept his essential Southern-ness, drawing people to his cause with Bluegrass gentility and charm.

Our canoe rounds a bend, and a cluster of cone-shaped thatched roofs pokes above the riverbank canopy. I step onshore and climb a footpath lined with purple hibiscus flowers and the red-and-yellow bracts of heliconias. Cabins strung with colorful hammocks hide among the trees. At an open-air dining hall perched above the river, McMeekin approaches, flanked by two staff members offering fresh strawberry juice and a hot washcloth from bamboo trays. Tall and balding, with a patrician face and a high furrowed forehead, he smiles and greets me warmly, his bourbon-smooth accent undiminished after decades away from his birthplace.“You’ve arrived in the middle of a small crisis,” he says.

I first met McMeekin in 1994, when my wife and I lived in Quito. We were all American expats, and Southerners. We spoke the same language. Common ground eased homesickness, recalls Eleanor Geiger, an Alabama native whose husband ran the Quito office of the U.S. Agency for International Development then. She also struck up a friendship with McMeekin, and even small details like his fondness for mayonnaise reminded her of home. “Douglas even puts it on asparagus,” Geiger says.

Back then, McMeekin was living in Quito and building UNICEF-funded schools and chartering bush planes to remote outposts to help Indians market traditional crafts. With Ecuador’s oil boom in full swing, he bought a motorized cargo canoe and broke ground on the jungle training center that would become Yachana Lodge on land he’d bought along the south bank of the Napo. By the time of my latest visit, the lodge was drawing thousands of tourists and university students each year. Most come for the cultural novelty—meeting shamans, learning how natives craft useful things out of vines and tree sap and piranha teeth, sampling roast palm weevils the size of your thumb (they taste like bacon).

Over a lunch of quinoa soup and palm heart salad, McMeekin briefs me on his latest financial hurdle, which involves the experimental boarding school he launched near the lodge in 2004. Thanks to the Ministry of Education’s failure to make good on a $70,000 pledge, Yachana High School is strapped for cash. Despite trying for years to wean his jungle projects off of charitable fund-raising and replace that with a self-sustaining revenue stream, McMeekin still hasn’t discovered a magic formula. After checking into my room, I slip on rubber boots and meet him for a somber hike to the school. Tromping a muddy trail, crossing creeks on crude footbridges and scaring up mangy chickens by village huts, we soon reach a clearing. A two-story wooden dormitory towers over several open-air classrooms, a bathhouse, a pond, and a dirt volleyball court. In an octagonal classroom, seventeen students clown nervously. Half the students have already left for end-of-term break.

Calling the meeting to order, McMeekin—known locally as Doog-las—explains in Spanish that change is afoot. He skirts the money issue and instead strikes an upbeat tone, saying, “I’m proposing something radical—an experimental gap year, starting next year.” He speaks Spanish in a Southern drawl, making no attempt to roll his r’s. Instead of having classroom lessons, he explains, students will divide up. One group might intern at ecotourism resorts around Ecuador; another might study English with U.S. volunteers. No tests, no homework, no grades.

And by the way, it will mean graduating in five years instead of four.

A few students grimly shake their heads, but McMeekin presses on. “Who’s in accord with the idea?”

Four students raise their hands.

A young ecology teacher named Robert Granja takes the baton, explaining how the plan fits the alternative school’s vision. “It is revolutionary,” he admits, “a bit crazy, but—”

“After all,” McMeekin chimes in, “I am the crazy gringo.”

Photo: Christopher Lamarca

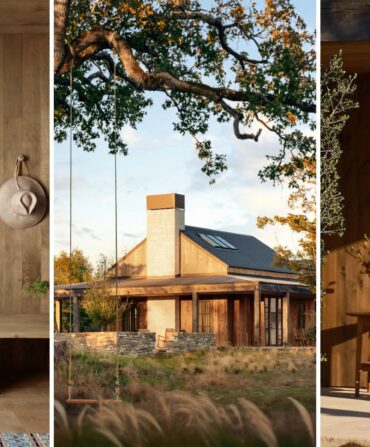

Opening the school in the first place probably seemed crazy. So did building a jungle lodge on a whim, with no tourism experience or investors. Perched above the river, the lodge is simple but alluring: private baths, generator- and solar-powered electricity, delicious meals, English-speaking local guides. It attracts couples tacking four days onto a Galápagos vacation, families, student groups. Guests see birds, butterflies, tarantulas, and the occasional monkey. One evening, as the sun sets over the Andes, a group of cultural anthropology students from the University of Santa Barbara sip tropical drinks at the lodge’s Drunken Parrot bar while Yolanda the parrot mascot begs for popcorn.

What makes Yachana Lodge unique, though, is how it feeds the foundation’s mission of educating people who live in the rain forest. It’s Ecuador’s only jungle resort run by local trainees, many of them students or graduates of Yachana High School. “The Amazon up to now has been almost entirely extractive—gold, oil, minerals, cacao,” McMeekin explains. “I’m trying to change the mentality, not just prepare people to get a job. I want to encourage people to think for themselves, to empower them.”

For similar reasons, he has also begun construction of the Yachana Institute across the river. He envisions the institute as a 150-person adult campus, the only all-purpose technical training center in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Like the high school, it will promote independence through sustainable work. The Ministry of Tourism has expressed strong interest in Yachana training its Amazon tour guides.

“I come up with a lot of ideas,” McMeekin says. “They don’t all pan out.” The commercial food projects—tilapia, chocolate, honey—never quite turned the corner. But those failures laid the groundwork for bigger successes: the lodge, the school, and now the institute. “When you stop coming up with ideas, you’re dead as far as I’m concerned.”

Still, the money problems never quite go away. Once, McMeekin mortgaged his Quito home to sustain the jungle chocolate project. When that failed, he lost the house.“With Douglas, there’s always something around the corner,” says Paul Reinert, a Missouri–based accountant and the president of Yachana’s U.S. foundation. “It might be a game changer, and it might not. He has a vision, and then he goes for it.”

If not for risk and failure, McMeekin might never have left Kentucky. He was reared in Lexington during the 1950s, the son of a talented architect who designed the vaunted Keeneland Race Course. Robert McMeekin’s other passion was exotic animals, and in 1958 he opened the Bird and Animal Forest zoo on limestone bluffs above the Kentucky River. Douglas’s mother, Martha, was something of a free spirit who struck out for Europe at seventeen. “In Italy, she got in touch with cousin Eleanor, who said, ‘Do stay for tea!’” says McMeekin. “She stayed for three years. In 1924, young women didn’t do that.” Later, with her sons’ help, Martha ran the zoo, bottle-feeding lion and bear cubs and once herding visitors into the gift shop after bears escaped their habitat by climbing a workman’s ladder.

As a boy, Douglas struggled with undiagnosed dyslexia. Preferring hands-on learning to burying his nose in books, he did poorly in school and would have flunked his senior year of high school if not for a teacher who caught a glimmer of his potential, overlooked his failing test scores, and gave him a D. “Nobody knew what dyslexia was,” says McMeekin, who cannot write Spanish despite speaking it fluently. “I was just a dumb kid. When a over b is upside-down, algebra doesn’t work very well.” The family sent his older brother, Robert, on a tour of Europe after high school graduation. In 1961, Douglas received the same offer but chose to go to South America. “They sent me on a well-planned two-and-a-half-week trip,” he recalls. “I came back eight months later.”

A few days after arriving in the Amazon port city of Manaus, Brazil, the nineteen-year-old met a shady but intriguing former U.S. Air Force pilot who claimed to have smuggled arms to Algeria and to Castro’s rebel forces in Cuba. When the man learned the Kentucky native had worked on a farm and knew his way around heavy equipment, he offered him a job on a logging boat loading exotic hardwoods with a crew of Spanish-speaking locals. Douglas mailed his parents a postcard—plans have changed!—slung his hammock on the deck alongside these hard-bitten characters, and set off upriver.

Though he eventually enrolled at the Uni-versity of Kentucky, McMeekin dropped out after failing several classes and went back to work at the family zoo. At twenty-six, he gave college another try, this time at the University of Arizona. He wasn’t a slacker, he says; he just didn’t learn well in a structured classroom setting. He graduated at twenty-eight with a degree in cultural geography, including a remarkable twenty-two credit hours of independent study—his creative way to avoid classrooms. “I always have a knot inside because I never got recognized for my aptitude,” he says. “That’s a big part of why I do what I do with education.”

After a brief stint as a researcher at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., McMeekin began buying and selling real estate in eastern Kentucky. He bought a bulldozer, built roads, sold improved land to “city slickers.” During the 1970s, he expanded his collection of heavy equipment and amassed a small empire—managing shopping centers, logging, renting out more than a hundred properties. Then came skyrocketing interest rates and the 1982 recession. “You pull the bottom card out, and all that goes poof,” he says. He filed for bankruptcy and walked away from it all.

The forty-year-old floundered for a while. On a soul-searching retreat at a Wyoming dude ranch, after nearly two weeks of solitary meditation, McMeekin experienced an intense emotional release—“the dam broke” is all he will say—and his vision cleared. “I decided I wanted to help others and ask nothing in return.”

While trying to sort out just how he might do that, he returned to Ecuador, where he had stopped on his formative South America trip decades earlier. He and a friend spent three weeks paddling the Tiputini River, which joins the Napo before it spills into the Amazon River in Peru. In 2010, a team of international scientists deemed this tiny corner of the Amazon one of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems, a magical place where a single hectare (roughly two and a half acres) holds more than 100,000 insect species and more types of trees than the United States and Canada combined. After camping among jaguars, howler monkeys, and giant anacondas, McMeekin returned to Quito alive with purpose. After an introduction by a friend, he marched into the office of Ecuador’s parks department. “Someone needs to preserve this area,” he recalls telling the director. “The man smiles, rolls out a big map, and says, ‘We’re doing that. It’s called Yasuní National Park.’” But the government had leased oil-drilling rights inside the park to U.S.-based Conoco. “Being shy and withdrawn as I am,” says McMeekin, “I went to the manager of Conoco.” The manager liked McMeekin’s ideas for protecting this fragile area and its people and hired him to work with local Indians. Petro-Canada later contracted him to do the same, despite his lack of formal training in environmental sciences or anthropology. “A lot of scientists know the studies,” he explains, “but it’s how you deal with people that matters.”

“He has a way of treating the indigenous with respect that they sense and marvel at,” says Eleanor Geiger, who volunteered at Yachana in the lodge’s early years. “I think Southerners like Douglas are fairly sensitive to working with people who have not had the same opportunities as they have. Maybe we all have some vestige of guilt about the racism that has existed in the South. His own dyslexia made him feel inferior to his peers. He has probably recognized that without an education, the indigenous will also be treated as inferior people.”

When I voice my perplexity at how the puzzle pieces of his life fell together, McMeekin shrugs. “I’m convinced I was in the Amazon in a previous life,” he says. “Now I’m back. My whole life I’ve been drawn to this part of the world and these people.”

The trunk of the giant ceiba tree thrusts into the sky like Jack’s bean stalk, and Juan Kunchikuy scampers up on a web of vines. The thirty-five-year-old Shiwiar Indian wears shorts and rubber boots. His long black ponytail trails down his back. Forty feet up, he tightropes on a limb away from the trunk, clutching branches for balance, then grabs a pair of vines and zips down to earth. The tour group I’ve joined cheers the performance. Next, Kunchikuy leads us on a hike through Yachana’s nature reserve, part of the lodge’s 4,300 protected acres. He points out a curare vine, whose sap boils down into a paralyzing toxin used to coat blow-dart tips, and then collects a hardened sap called copal and lights it, explaining its uses as both candle and incense.

Yachana Lodge’s head guide and one of McMeekin’s indigenous protégés, Kunchikuy grew up in a village on the Rio Corrientes near Peru where his grandfather displayed shrunken heads of slain enemies. The tumult he has lived through is etched upon his body in a collection of scars from an Amazonian alligator, a piranha, vampire bats, and a freshwater stingray. When he was a child, a shaman plunged a blade into his chest to extract another shaman’s curse.

That scar had healed by the time he met McMeekin. Disillusioned after six years as a petroleum consultant, McMeekin had quit and begun working directly with indigenous groups. At seventeen, Kunchikuy left his isolated village to work for McMeekin’s foundation. Impressed by his aptitude, McMeekin sent him to Boston to study English. Bright, multilingual, and a whiz at rain forest ecology, Kunchikuy became Yachana’s most popular guide and a member of the foundation’s board of directors.

Robert Granja, the ecology teacher, is another McMeekin acolyte. Though not indigenous, he grew up nearby on the banks of the Napo. After helping build Yachana High School, he joined the inaugural class, and after graduating became a guide and a teacher. His English is impeccable, the result of a foundation-sponsored stint at a Pennsylvania college. In 2010, he flew to Tanzania to represent Yachana at an education conference. Granja also advises local farmers about how grafting and biofertilizers can boost the yield of cacao beans fivefold over traditional growing methods. “That reduces deforestation and creates a better life for the farmer and his family,” he explains. His father used to fish with dynamite, setting off charges in ponds and streams and scooping up dead and stunned fish. “I was able to convince him that that’s not sustainable,” Granja says.

Early one morning, I say goodbye to McMeekin in the rain. He’s leaving to catch a flight to the States to gin up financial support, standing on the bank beneath a red umbrella. The river is swollen and brown, shoving branches and logs and God knows what else beneath the murky surface toward the Amazon. As the canoe’s engine growls to life, the motorista pauses to let a half-submerged palm trunk drift past, and then guns it. The long boat arcs into the current beneath a washed-out sky.

At an age when many men are cashing in IRAs and hitting the links, McMeekin owns few material possessions. He keeps an apartment in Quito and a spartan two-room cabin in the rain forest. “I have no money today,” he says, “but I have more than most people.”

Early this year, when I reach Mcmeekin by Skype at his apartment in Quito, he drops a bombshell: He has sold Yachana Lodge. A Canadian social enterprise called Me to We needed a facility for its volunteer trips and made him an offer, and McMeekin quickly recognized an opportunity to clear his debts. The company’s founder bought the infrastructure and three hundred acres but let McMeekin keep the Yachana Lodge name and concept. He was so taken by the charismatic Kentuckian and his mission, in fact, that his company’s charitable wing also made a sizable donation to the Yachana Foundation. With this fresh start, McMeekin has already broken ground on a new lodge across the Napo, where he’s also building the institute. “It’s an absolutely spectacular spot,” he says. “The plan is to be open by May.”

Meanwhile, Robert Granja and other members of Yachana’s staff have another goal in mind. They want their boss to relax more. Granja imagines a float trip. The day is sunny in this vision, and Doog-las, wearing shorts and sunglasses, drifts past Yachana on an inner tube, an icy caipirinha in his hand.