On Tuesday, January 19, a massive fire erupted at Edwards Virginia Smokehouse in Surry, Virginia. The flames moved quickly, engulfing the red clapboard building in a fierce instant. Mercifully, it was lunchtime and most of the venerable food company’s employees were out on their break. No one was injured, but the blaze reduced the smokehouse to cinders.

I was home in Brooklyn when I heard the sad news. Just a few weeks before, at Christmastime, I’d shown my mother how to go online and order a petite ham, already cooked and suitable for our family’s smallish holiday gathering. We had it with biscuits Christmas Eve alongside fried chicken and mashed potatoes and peas. There was plenty left over for sandwiches the next day, and still enough for picking as the old year gave in to the new. Like everything I’ve ever had from S. Wallace Edwards and Sons, our ham was salty, toothsome, irresistible. That it might have been our last is a thought I’m loath to contemplate. As I write this, Edwards is, thankfully, taking steps to rebuild, but it’s unclear exactly when the company will return to its preblaze output.

And, oh, what would my father say?

Born in Newport News, Virginia, Bill Styron spent most of his life in exile from the South. After a stint in the Marines and graduation from Duke University, he hightailed it to New York with dreams (soon enough fulfilled) of becoming a literary star. While in Rome on a fellowship a few years later, he met and soon wed my mother. They returned to the States, bought a house in rural Connecticut, and there my father lived and wrote for more than fifty years, until his death in 2007. He didn’t sever his roots. In fact much of his best work—Lie Down in Darkness, The Confessions of Nat Turner, A Tidewater Morning—relied on the strength of his Southern identity. But he definitely assimilated. I don’t remember a lot of talk about the old country in our house, and there certainly wasn’t any nostalgia for the more bitter truths of his Jim Crow–era childhood. My siblings and I grew up full-fledged New Englanders. We skied, rooted for the Red Sox, and cracked lobsters freshly plucked from icy coastal waters. But three or four times a year, my father would prepare an Edwards Wigwam ham and we would dogleg deep into the heart of Dixie.

Hanging It Up

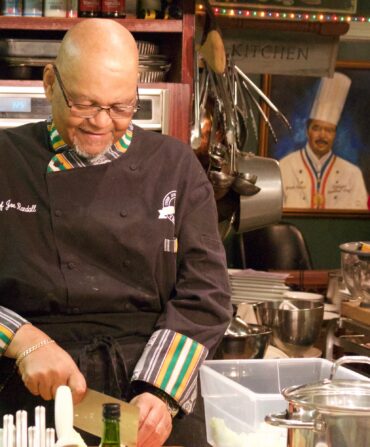

William Styron prepares to slice some Edwards ham in his Connecticut kitchen in the late 1970s

The hams hung from a hook beside our kitchen sink. Twenty-pound wonders, salt cured, dry aged, and sheathed in tan canvas adorned with a zigzag motif. My father always had one at the ready, ordered by phone in the days before the company mailed catalogues, and eons before the Internet. Edwards was, and remains, a family-run operation. S. Wallace Edwards got his start selling ham sandwiches on the Jamestown–Scotland ferry. His Surry smokehouse opened just across the James River from Newport News in 1926, the year after my father was born. When Dad was still a boy, his mother died after a long battle with cancer. I’ve always imagined the local delicacy like Proust’s madeleine, evoking the warmer memories of his complicated youth.

Holidays were not exactly my father’s favorite time. He hated the chaos, and dreaded the parties my mother planned, with their guest lists that grew like kudzu. Eventually, though, his hospitable spirit emerged. He brought in firewood, prepared the wines, mellowed and grew merry. But really nothing got him quite into the groove like his preparation of a Virginia ham. The brown sugar glaze was concocted with loving intensity. He checked and rechecked the oven, brought a craftsman-like approach to cutting the meat. If you passed through the kitchen and were open to an apprenticeship, you could expect to give up a chunk of your day to a garrulous tutorial on the direction of the grain, and how exactly to lay the slices on the platter.

But by then you would have missed the first, key step in the Wigwam experience: soaking the ham. Usually for days. It was a desalination process that also sloughed off impurities, like mold, acquired during the months of postmortem aging. Needless to say, it drew out some of the swine’s more God-given humors as well. When I was very small I sometimes slept in my older sister’s room on Christmas Eve. One year, after shuffling into her bathroom for a late-night pee, I caught sight of something so horrifying I practically levitated off the toilet and down the sloping hall. “Daddy!” I hollered in the dark of my parents’ bedroom. “There’s a dead man in Polly’s bathtub!” It took many shuddering minutes before he could convince me that it was the Christmas ham I’d seen beneath the murky water.

Fourteen years ago, I married a man with Southern roots. Every Thanksgiving, we fly down to his parents’ farm in LaGrange, Georgia. My sister-in-law bakes pies and drives them over from Charlotte. But since Delta doesn’t make much space in the overhead bin for prepared foods, I order an Edwards ham. It’s a nice family tradition, something to pass along. I don’t know what we’ll do this fall.