Thurgood Marshall dreamed of becoming a lawyer. His parents, a steward and a teacher, had instilled in him the importance of the Constitution; his father loved to watch proceedings at the local courthouse, and the family often debated trial outcomes and issues of the day at the dinner table. So when Marshall graduated college in 1930, he set his sights on the University of Maryland School of Law, in his hometown of Baltimore. There was just one problem: The school was segregated, and Marshall was black.

A handful of years later, after he had earned his degree instead from Washington, D.C.’s Howard University School of Law, Marshall represented another well-qualified black man who had been denied admission to the University of Maryland School of Law, in Murray v. Pearson. The young lawyer argued that the state violated Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate but equal” ruling, since no public black institutions in Maryland offered a similar educational option.

With poetic justice, Marshall won. It would be his first major civil rights victory—but not his last. He would go on to triumph in twenty-nine of the thirty-two cases he argued before the Supreme Court of the United States, most notably 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, a decision that declared segregated public schools unconstitutional. The great-grandson of an enslaved man—Thoroughgood, for whom he was named—was breaking chains.

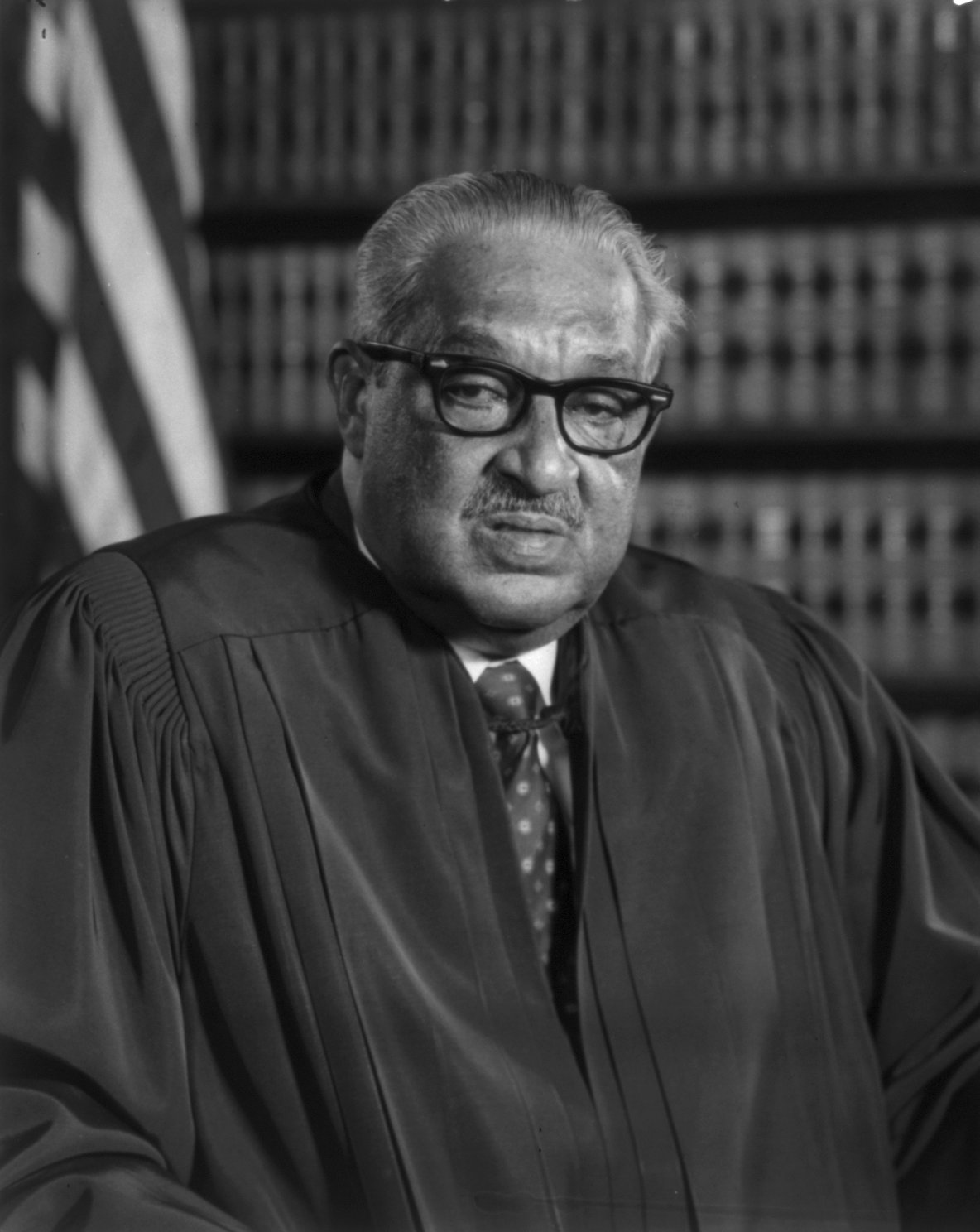

Library of Congress

Fifty years ago, on August 30, 1967, Marshall broke something else: the glass ceiling of the U.S. Supreme Court. After the Senate overwhelmingly confirmed Lyndon B. Johnson’s nomination of the man the president had named Solicitor General two years earlier, Marshall became the first African American to sit on the bench. At the time, Johnson, a Texas native, said it was “the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man, and the right place.”

Marshall served twenty-four years, retiring in 1991 and dying two years later. But his legacy beyond the bench lives on, from Marshall—a new film out this October starring another Southerner, Anderson, South Carolina’s Chadwick Boseman, as the young civil rights attorney—to the names of government buildings and libraries across the country. Including one, appropriately, at the University of Maryland School of Law.