We met Ginger when she was four months old, at an adoption fair near our local farmers’ market. It was a chaotic scene, dogs barking everywhere, my husband and I wrangling our three children as they ran from cage to cage. I spotted Ginger lounging quietly on a blanket next to her overly eager mother and sister. She was an all-black mixed breed, part terrier and shepherd with a touch of chow that showed itself in a partially black tongue.

When I picked her up, I mistook her lying limp in my arms for shyness. Our youngest was already more than a year old, and this puppy felt like holding a baby—she would be the perfect mellow fit for our family of five. It wasn’t till we got home that we realized she wasn’t so much shy as riddled with fear. When I first approached her with a leash, she lay on the ground and peed. I became her only comfort—other people unnerved her. She followed me from room to room so often I called her my needy alcoholic wife.

Our fifth-grade daughter, Rachel, discovered Buddy, the street urchin we did not choose, sitting in the middle of our driveway on a late spring afternoon more than a year later. By the time the all-white corgi mix appeared, full of male swagger and sass, Ginger was living in full-blown anxiety every day. She peed when we came through the door; cowered when anyone came near, particularly men, including my husband; pooped in the backseat on car rides; and shook at loud noises for hours, sometimes days, on end. A door slam would send her burrowing into couch cushions. Fireworks launched her into such frenzy that she tore through foundation vent screens and holed up under the house for more than twenty-four hours.

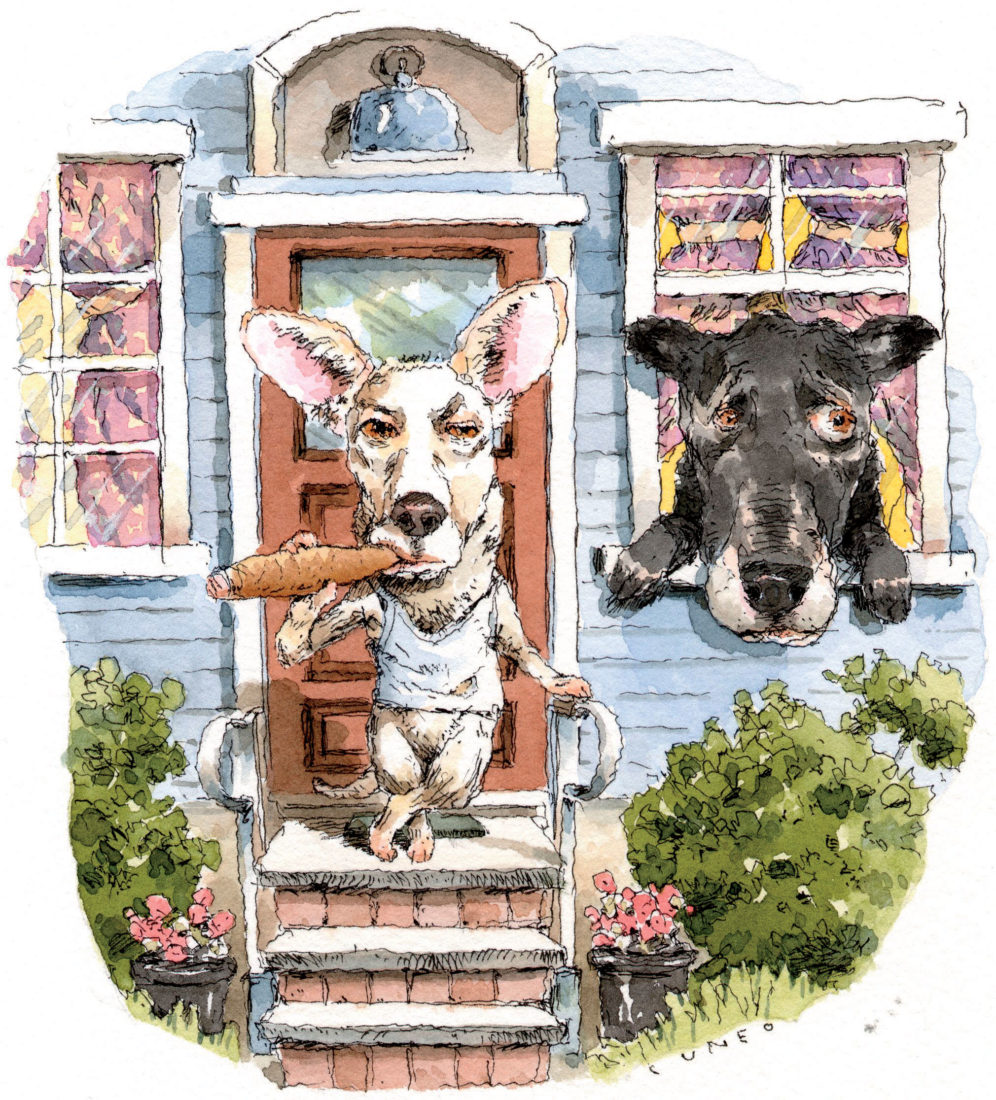

When Rachel came through the door yelling about a lost dog, I went to inspect, and there was Buddy, standing on our front porch surveying the neighborhood as if he owned the joint. This tough guy, with ears as big as his head, casually glanced at me, walked into our home, lifted his leg, and peed on my couch. If I said to my husband once, “We are not keeping this dog,” I said it a hundred times while we searched for Buddy’s owner. After no one answered the newspaper ads, or responded to the posters we hung, I drove his macho butt to the pound, then cried all the way home. We went back for him the very next day and paid for what we could’ve had for free. Three days later, we brought him home, clipped, chipped, and claimed, no more humbled than the day we found him.

Buddy was not only Ginger’s opposite in size and color, the ivory to her ebony, he also wasn’t afraid of anything. The animal loved everyone but didn’t ask for affection—he took what he wanted. The dog was a male trollop. When our friends came to visit, he climbed onto every lap and faced each person, paws on chests until they succumbed to his will. Our two-year-old, Joe, was the one who named him, and every night when Joe went to sleep in his big-boy bed, Buddy crawled in beside him under the covers and placed his head on the pillow. I’m not sure he understood English, because he never answered to his name, which could have been because of the multitude of burs the vet initially fished out of his ears, or because he didn’t give a damn whether you wanted him to come or not. He had his own agenda.

Buddy very quickly became Ginger’s taste tester, her first line of defense against the world. When she got a glimpse of the life she was missing, our prissy, freaked-out, tap-dancing-on-toenails queen shifted. If Buddy got attention, she wanted some, too. Whereas before she cowered, Ginger now rested her snout on a knee until her head got a pat. If Buddy made a beeline for a family member, she, being the longer-legged dog, got there first and pushed him out of the way. If he went in the car, so would she, and although she still cried and shook, the backseat pooping stopped. She slept curled between the twin beds of Rachel and our seven-year-old, Nick, oblivious to the nightly fight over which kid Ginger liked more.

Outside, in the backyard, Buddy chased anything that crawled, flew, or stepped within our perimeter. Dead rats, birds, and squirrels lay randomly strewn throughout the yard. Ginger started growling at deliverymen and strangers. We took both dogs on hikes to release some of that energy, and it was there, leash free, that Ginger’s true personality emerged as she rounded us up, running crazy eights between the first and last hiker, herding us like sheep. Her sheep.

Buddy was a runner. We knew that so were careful with gates and open doors, and on those hikes we kept him on leash or peeking out from my backpack. At home, he sat on the back of the couch so he could peer out the window, dreaming of his gypsy days, no doubt. Still, one day he slipped out and just as quickly as he had arrived in our lives, he was gone. We told our kids it was likely he was trying to get back to his people, find his way home, but I knew better. That dog didn’t belong to anyone—he was his own numero uno. Par for the course, I thought. He waltzes in here, gets two meals a day, treats, and a warm bed. He claims us as family, then leaves, taking my children’s hearts with him. Not my heart, of course. I never liked the damn dog. That’s what I told myself, and I meant it.

In the weeks that followed, Ginger became an insomniac. She patrolled the house all hours of the day and night. The tap tap tap of her toenails made me weary. She spent days going from window to window looking outside to the street beyond. She covered Buddy’s food bowl with the rug and pushed her own virtually untouched meal into the corner beneath the counter stools. One early morning I went into the backyard and before me was a possum massacre, carcasses everywhere—Ginger’s handiwork, an ode to Buddy. She had become the protector, the guardian of the garden.

Six weeks later, the phone rang and my husband answered. I could hear the man on the other end of the line, calling from the next county up, some thirty miles away, asking if we had lost a dog.

“Depends,” my husband answered, glancing back at me, knowing my attitude about the whole thing. “Does he have big ears?”

When the man laughed and said yes, I burst into tears.

Buddy waltzed, all tra la la, through the front door, while Ginger ran in circles, barking, rejoicing at the prodigal son’s return. He marched right past her, jumped onto the couch, and promptly fell asleep for two straight days. Ginger climbed up next to him and followed suit. Buddy ran off six more times in those first two years before he gave up on the road altogether. Whether he finally chose us or was just plain tired, we will never know, but I took sadistic satisfaction in the knowledge that he never got very far before being returned. The same kind of pride I imagine he took in being the little rat bastard who taught Ginger, and all of us underlings, a little something about the rewards of embracing the great unknown.