Early on Halloween morning, a beach walker near the pier in Garden City, South Carolina, came upon a disturbing sight: a five-pound green sea turtle lay washed up in the sand, bleeding heavily from a deep cut that ran from the top of its neck to beneath its left shoulder. Volunteers rushed the turtle nearly two hours south to the Sea Turtle Care Center at the South Carolina Aquarium in Charleston, where he was affectionately named Michael Myers in reference to the horror film Halloween.

“The laceration was possibly from a boat propeller,” says Melissa Ranly, the Sea Turtle Care Center manager. “But it had a jagged edge, so it could’ve been a shark bite. Whatever it was, it’s hard to believe it didn’t take his little head off.” Ranly spent Halloween night beside Michael’s tank, making sure he didn’t bleed to death.

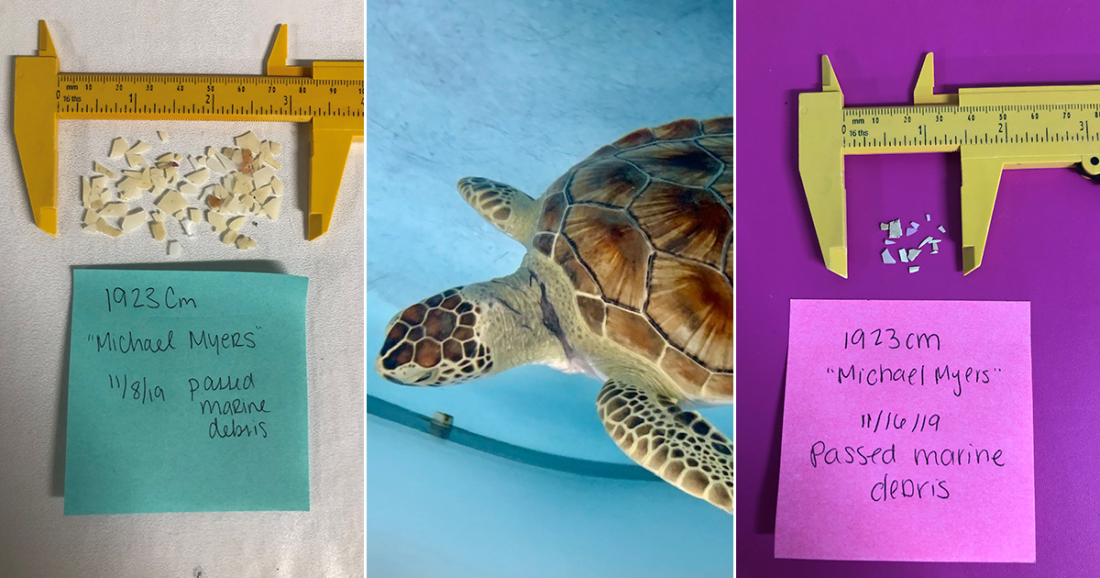

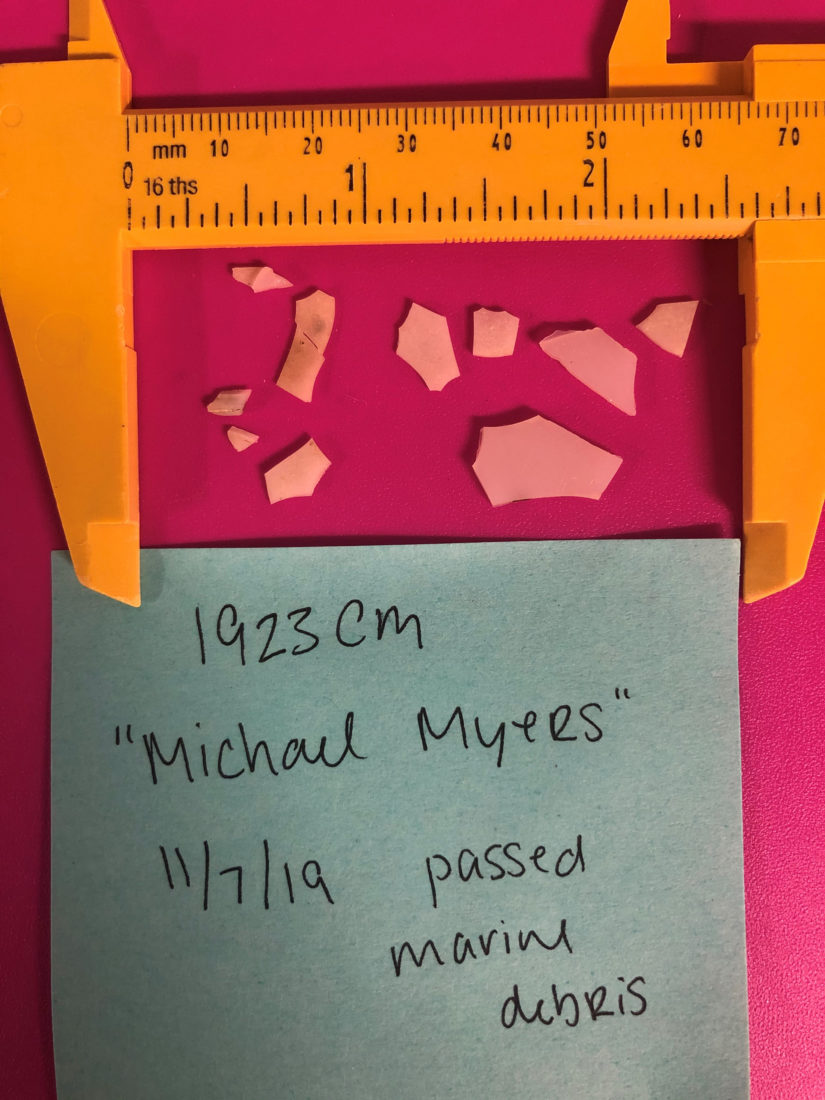

Since Michael wouldn’t stop moving, it took weeks for his wound to heal. “The last pieces of the scab just came off,” Ranly says. “We’re so happy to see the soft tissue is filling in.” But unbeknownst to the team when the turtle was brought in, he was dealing with more than just the laceration. About a week after he entered the hospital, hard plastic and food wrappers, which are not dense enough to show up on CT scans or X-rays, began appearing in his feces. “There were over eighty pieces of plastic in his first defecation,” Ranly says. “To date, he’s passed 136 pieces. That’s the most plastic we’ve ever seen in one animal.”

Luckily, Michael Myers seems to have now passed all the debris in his system. His story, though, is not uncommon—and often has much grimmer results. Plastic in a turtle’s stomach can imitate the sensation of being full or block the digestive tract altogether, causing the turtle to starve. Other times, shards can puncture internal organs, or toxic chemicals can leach into the animal’s system, disrupting the endocrine system and other bodily functions. And the problem seems to be getting worse. “We’ve been tracking marine debris in all our patients since we opened in 2000, and there’s been a big upward trend in the last five years,” Ranly says. “Facilities that take in smaller turtles and washbacks [hatchlings that get pushed back to shore after crawling out to sea], find that almost 100 percent of turtles that die have plastic in their systems.”

That trend is why the Sea Turtle Care Center has been working to educate people on the importance of cleaning up beaches and reducing our reliance on single-use plastics. “We’re encouraging people to do a plastic audit in their lives and think about ways to reduce it,” Ranly says. “These sea turtles are showing us how important that is.”

With the plastic flushed from his system and the laceration healing, Michael Myers is now well on his way to a full recovery and release. “He’s still very anemic since he lost so much blood, but the goal is to get him back out there,” Ranly says. “He’s a success story so far. Given half a chance, turtles are resilient.” Humans just have to give them that chance.

MORE: How to Save a Loggerhead