It’s a cool night, but Matt Jones is sweating. That has something to do with nerves, and something to do with fire: Before him, in a 600-cubic-foot kiln the ceramist built himself, many months’ labor is cooking. Shelves upon shelves of pots—some 1,200 pieces, from six-inch soap dishes to 200-pound planters—pulse white-hot as flames tear past and leap from the chimney stack. “A river of fire,” Jones says as he feeds another poplar slab into the blaze. In increments of one hundred degrees per hour, he is pushing toward 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit, when the glaze will vitrify to seal his pots in a skin of glass.

Photo: Beall + Thomas

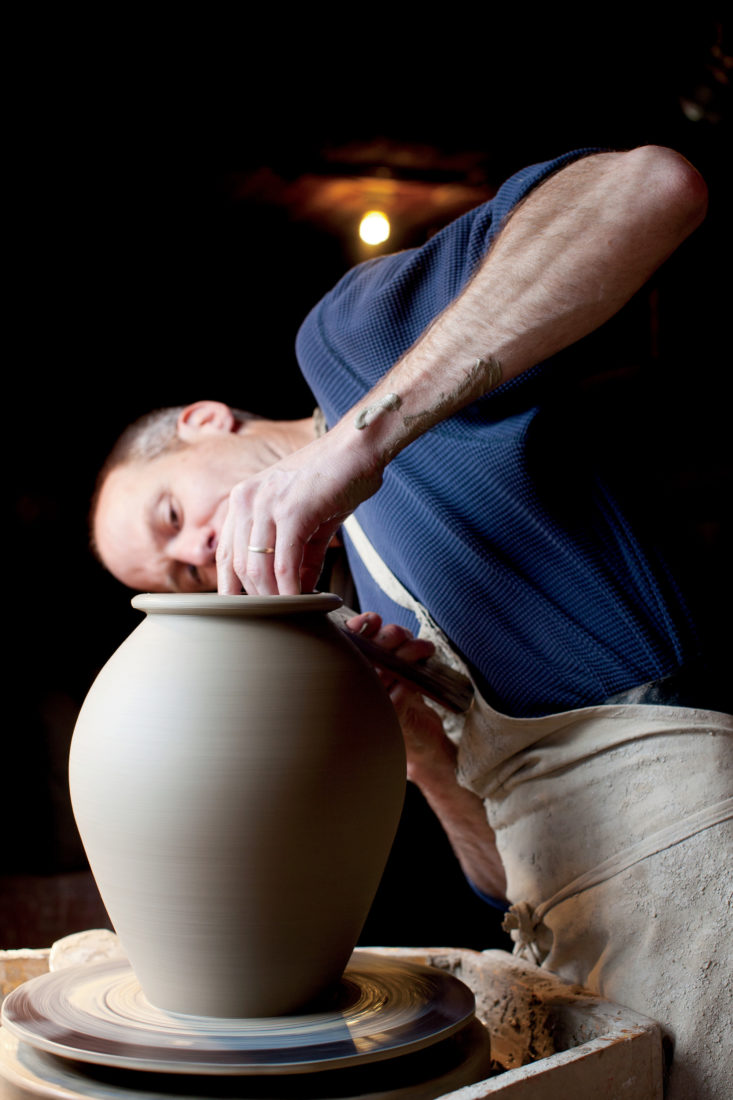

The Wheel Deal

A work in progress.

He doesn’t have to do it this way. An electric kiln would accomplish the work in a fraction of the time, with far more predictable results. But to opt for the easier way now would dishonor the work that has come before: the digging of the alluvial clay; the preparing of the traditional glazes; the careful slip trailing, texturing, and painting. It would be like surrendering homegrown heirloom tomatoes to a bottle of Prego. “The onslaught of industry has put cheap, largely impersonal objects into our hands,” Jones says. “I want something ragged and soulful.”

His work draws on nineteenth-century American pottery traditions—jars, jugs, and crocks historically used for pickling produce or storing salted meat. For his glaze, Jones turns to recipes used in the antebellum potteries of Edgefield, South Carolina, renowned for their exceptionally durable stoneware. It’s not simple nostalgia that inspires him, but reverence for his potting forebears. Mostly unsung, his heroes used local ingredients to produce pots that worked hard and lasted long. Pots that, in form as in function, endured.

Photo: Beall + Thomas

Finished pieces in his gallery.

First called to the potter’s wheel as an undergrad at Earlham College, Jones apprenticed in Cornwall Bridge, Connecticut, and Pittsboro, North Carolina, before he and his wife, Christine, set up shop in Big Sandy Mush, a remote rural community west of Asheville with ready access to quality clay and room to accommodate their nascent venture: Jones Pottery. With the help of loyal friends and family, Jones constructed a workshop, a showroom, and—his special pride—the cross-draft kiln. His understanding of his craft runs as deep as the clay beds he excavates. A keen student of geology, anthropology, and history, Jones is as comfortable discussing rock plasticity as he is European interpretations of Chinese floral patterns. That’s fitting for a man whose life and work are so tightly woven. “I love that I know where my clay came from,” he says. “That ashes from my woodstove are my primary fluxing agent…that a water-powered pulverizer turns my beer bottles into a glaze ingredient.”

Photo: Beall + Thomas

One of his hand-painted designs.

Jones considers himself a craftsman more than an artist, but his skill with the brush clearly renders art of his craft. His decorative patterns are playful evocations of the natural world—speckled trout and blue herons, camellia blossoms and honeysuckle vines—that recall a childhood on the Carolina coast. The effect is exquisite and has earned his work a place in numerous galleries, museums, and private collections. His biannual kiln sales, held after his spring and fall firings, draw loyal customers from across the South. (Look for this year’s spring sale Memorial Day weekend.)

Beautiful as they are, though, these are works of art that work. If you doubt that, have a look at Jones’s own kitchen, where most every vessel bears the mark of the kiln. Clients don’t just collect Jones’s casserole dishes, pie plates, and pasta bowls—they use them. “I look at the objects people once surrounded themselves with,” Jones says. “All of it was handmade and useful, sometimes humble, but deeply beautiful and real. I want my pots to honor that—the spirit of those who preceded us.”