In January, I read an article in the Wall Street Journal about a change in strategy at the St. Joe Company, the former timber and railroad outfit that’s one of Florida’s largest landowners. After the success of Seaside, the award-winning New Urbanist community founded in 1981 on the northwest Florida coast, St. Joe began working on its own master-planned developments, one of which, WaterColor, abuts Seaside and the other of which, WaterSound, is just down the road. Like pretty much everybody else in the luxury real estate business, St. Joe got slammed in the housing bust, and its new board of directors signaled to the SEC that it would be significantly reducing expenditures in the planned communities, which was the peg of the piece. Since I already knew that, I was about to turn the page when the last line of the story, written by a fellow named Robbie Whelan, caught my eye. The “area,” he wrote, “is often derided for its deep southern feel and muggy climate.”

Now, as it happens, I have spent a large part of my life in this particular “area,” also known as the Panhandle. In fact, when I read the article, I was sitting in the living room of the house in Seaside my mother has owned for the past fifteen years. She’d spent much of her own childhood in an entirely different Florida, vacationing with her parents and grandparents in Palm Beach at the Breakers hotel. The “feel” there, as at so many of the other über-social, high-WASP (or at least formerly high-WASP) resorts along Florida’s South Atlantic coast, is not so much regional—Deep South or otherwise—as tribal. The Palm Beach Breakers is not all that different in look and provenance from the Newport Breakers (a lot of Mr. Vanderbilt’s summer houseguests in Rhode Island were also winter guests at Mr. Flagler’s hotel), or, for that matter, from the Andrea Doria, the cruise ship on which my grandparents also vacationed before it sank.

My mother hated the Breakers. She and her nurse had to dress up just to cross the lobby to the pool; she spent her afternoons playing shuffleboard with my great-grandfather. There’s a picture of him there, with my great-grandmother and my grandmother and some close family friends. The men are in tropical-weight suits with ties and pocket squares; my grandmother has on a printed silk day dress, white pumps, and a fair amount of diamonds and pearls. No one is smiling.

So it was that my own family spent vacations in Destin at the Frangista Beach motel. With her marriage to my father, my mother had already made one revolutionary move, from the plush confines of Nashville’s Belle Meade to the swampy wilds of the Mississippi Delta; the leap from Palm Beach to the Panhandle was sort of the same thing. At the Frangista, the screen doors of the linoleum-tiled “suites” opened directly onto the beach, we rarely wore anything other than bathing suits, and there was certainly no shuffleboard. Instead, there was a next-door RV park, temporary home of one of my earliest crushes, a guy named Larry who caught rays atop his Winnebago and whose straw cowboy hat featured a band made of Pabst Blue Ribbon pull tabs, which were in ample supply.

My brothers and I and all our friends fished and swam and made ourselves peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for lunch, and at night we went with our parents to restaurants like the Sand Flea or the Blue Room for pompano and stuffed flounder. The grown people stayed up late drinking whiskey they bought at the Green Knight, a package store named for the garishly painted figure out front, while we went crabbing with the help of flashlights and the beach-loving dog Dexter, who belonged to my father’s best friend, Nick. I’m sure that by the time July and August rolled around it was, in fact, plenty “muggy,” but we didn’t notice. That was what the water, and the ever-rumbling Frangista window units, were for.

It was easy and it was fun and I guess I’d been visiting for at least fifteen years when I discovered another photo of my grandmother at the beach, this time at a friend’s vacation house on the bay near Destin, a place I never knew she’d been to. She has on capri pants (then better known as clam diggers), a sleeveless blouse, and no shoes. She doesn’t know the photo is being taken, and she’s leaning forward on her toes laughing, with what appears to be an actual can of beer in her hand. The photo astonished me for a great many reasons, not least because in all the years I knew her I had never seen my grandmother refresh herself with anything other than Beefeater’s in a Baccarat glass, or shed her shoes in public for any reason other than to have someone paint Revlon’s Windsor on her toenails.

Maybe that “deep southern” pull was strong enough to get my grandmother, a woman who once took my cousin and me trout fishing in exactly the same getup she had on in the photo from the Breakers, to shed her shoes. Whatever—I was just so relieved to learn that at least once she’d had some fun in the sun. The rest of us are still at it, though when Destin got a tad too overrun with high-rise condos, we moved our base of operations about twenty miles southeast to Seaside, which brings me back to the article.

First, let’s get past the fact that the writer seems to imply that the same fate that’s befallen pretty much every luxury real estate developer in the entire country happened to St. Joe because its land happened to be in a place that’s hot and feels like the Deep South, and move on to the term itself. On this point, Mr. Whelan is right, at least historically. There are endless discussions about which states make up the Deep South, but by at least one definition they’re the seven that left the Union prior to the firing on Fort Sumter, which are, in order of secession, South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas.

In the century and a half since the war, the makeup of Florida has changed dramatically, but the Panhandle, bounded by Alabama to the west and the Apalachicola River to the east, remains essentially—especially—Southern. Beginning as early as 1811, its citizens lobbied to be annexed to what is now Alabama at least seven times and finally passed a successful referendum in 1869. By that time, though, Alabama’s carpetbagger government rebuffed the annexation as too expensive, a blow happily remunerated almost a hundred years later by the opening of the Flora-Bama Lounge, which straddles the line between the states.

The problem is not that the Panhandle can’t be correctly called “deep southern,” I just didn’t know we were still being “derided” for it, and not just occasionally but “often.” With the exception of some pesky periods in our not-so-distant history when we could rightly be called inhospitable or far worse, our good manners and friendliness have generally been considered a draw. What I think Mr. Whelan really means by “deep southern feel” is “redneck reputation.” Let’s not forget that there’s an annual mullet toss at the Flora-Bama, or that Tom T. Hall’s song “Redneck Riviera” includes lyrics that recall the likes of my old friend Larry: “Nobody cares if Gramma’s got a tattoo or Bubba’s got a hot wing in his hand.”

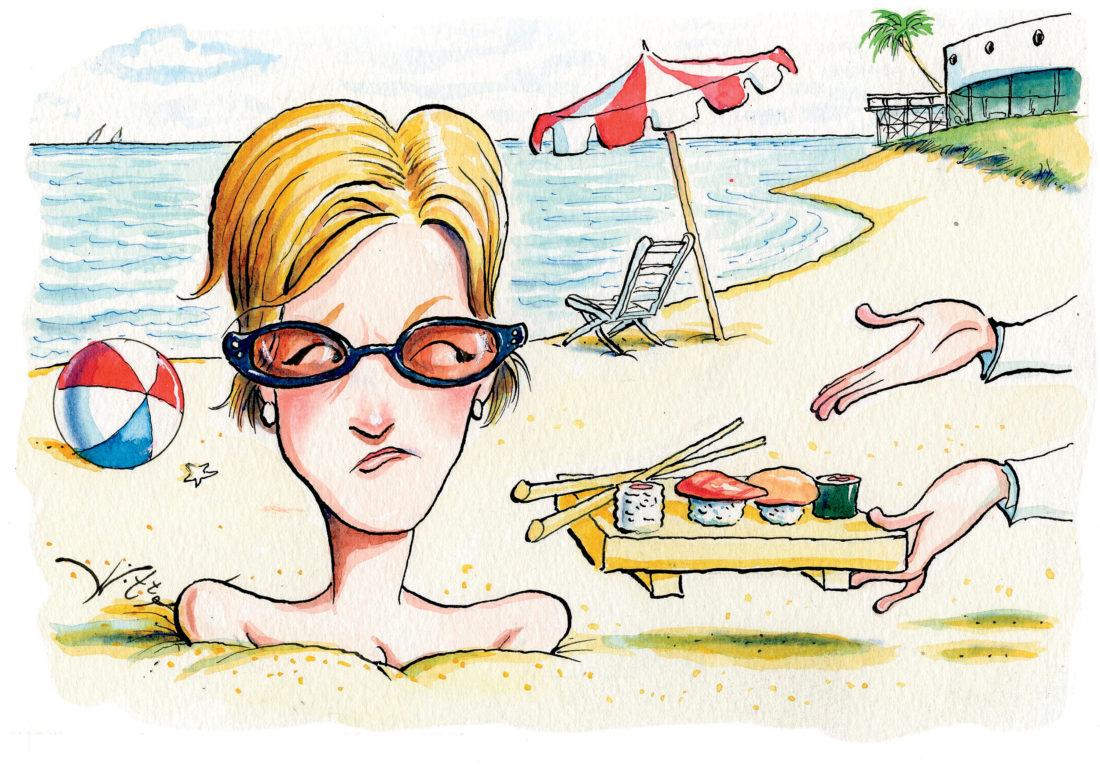

But Mr. Whelan has clearly not visited in a long while, if ever, because I’m worried that the redneck aspect of things is dissipating at far too fast a clip. Were she still with us, my grandmother could find plenty of dry martinis to sip on as well as swanky restaurants in which to wear her finery. Within walking distance of my mother’s house alone there are three places to get sushi, an amazing handmade pizza place, an organic juice bar, two wine bars, a gourmet grilled cheese stand, a James Beard–nominated restaurant, and a “shrimp shack” that sells melt-in-your-mouth lobster rolls accompanied by splits of champagne. Then there are the facts that the New York Times regularly sells out by 8:00 a.m. and Sundog Books in Seaside is one of the three or four best bookstores in the whole country.

All of this is actually good news, especially since there’s still plenty of ingrained grit and goodness to go around. Seaside’s Modica Market reminds me of the family-owned Italian grocery store I grew up going to in the Delta. Charles Modica and his sister Carmel always greet me with a hug (and, usually, a draft beer on the house), but they also know to reserve some bottles of my favorite olive oil, which, until now, I’ve only ever found in Córdoba, Spain, and Charles’s hand-cut rib eyes are the best I’ve ever eaten. Likewise, the weekly farmers’ market features fresh eggs, collard greens, and pink-eye and purple-hull peas among the more gourmet offerings, and equidistant from the nearest sushi place is a diner that still sells deep-fried grouper on a bun. On balance this “deep southern feel,” if not flat-out redneck vibe, is still working for us. Add the clearest blue-green water in the world and the powdery white sand (made of quartz washed down from the Appalachians by ancient rivers), and I’m with Tom T.: “Down here on the Redneck Riviera there ain’t no better living anywhere.”