Arts & Culture

Unearthing the Art of Cora Kelley Ward

A cache of paintings by the unsung Louisiana artist leads the author on a yearslong journey to fill in the details of her unconventional life—and understand why her work grabbed him and wouldn’t let go

Photo: Marianna Massey

From left: An untitled painting by Cora Kelley Ward in collectors Tim and Dana Miller’s home in Lafayette, Louisiana; Ward in 1950; a selection of Ward’s artworks from the 1960s and ’70s.

Her name was Cora Kelley Ward, and they’d arranged her paintings in piles on the floor of a loading bay. At the start of the sale there had been around eight hundred works to choose from. Now, four days later, there were fewer than three hundred left, and the price for a canvas had been reduced to a dollar a square foot, down from two dollars.

I looked out at the bizarre scene and did the math. For $54 I could buy a painting big enough to cover the better part of my living room wall. Dinner last night had cost more than that.

It was May 9, 2012, at the Hilliard Art Museum on the campus of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. I wasn’t sure about the giant pictures of what looked like Easter eggs, but I did like the colorful action painting displayed at checkout. Gobs of blue and salmon floated on its surface, each form carved with a loose black line. The painting was a classic example of mid-1950s abstract expressionism.

“Any more like this?” I asked a museum worker.

“Too late,” she answered and gave her head a shake.

I didn’t need more art—my wife and I already owned hundreds of paintings, many of them stored in closets and under beds—but my friend Tim Miller had pestered me with calls until I made the two-hour drive from my home near New Orleans. Tim and his wife, Dana, are longtime collectors of Southern art. “I’m thinking about buying everything that’s left,” he said. “I should have enough in my checking account.”

The artist had experimented with different styles over her career, and the sale still had examples from her geometric, color-field, and pour periods. Cora Kelley Ward had died from cancer in 1989, and her family stored the collection for twenty years before donating it to the Hilliard.

“Incredible, huh?” Tim said. He was picking over watercolors on a folding table, each priced at fifty cents.

“It’s nuts,” I told him.

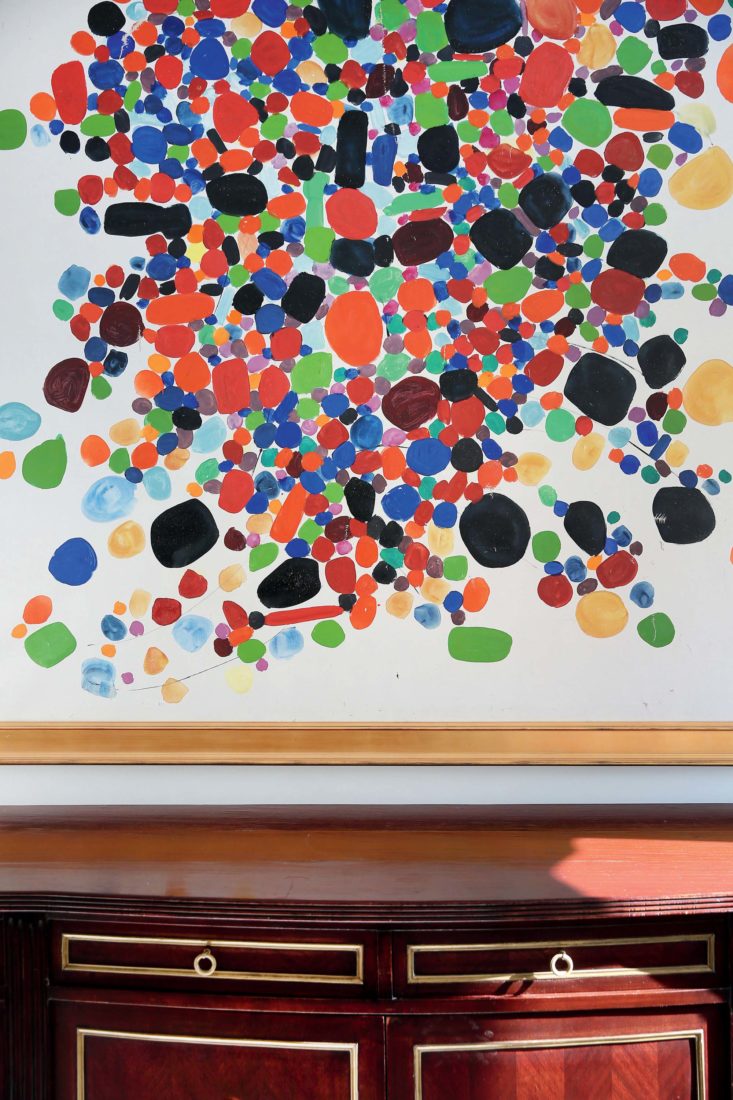

Photo: Marianna Massey

A 1959 acrylic painting by Ward in the Millers’ home.

Born in 1920, Ward grew up in and around Eunice in the state’s Cajun country. There are plenty of rice and crawfish farms in that part of the world, but it would be a stretch to describe it as a breeding ground for modern artists. She moved to New Orleans at seventeen, became a registered nurse, and married a doctor named Simon Ward. By all accounts, the marriage was an unhappy one, at least for Cora. In response to a deep personal need to make art, she began taking classes at the Newcomb Art School, even as Si Ward belittled her dream of becoming a painter. The more she filled up canvases with abstract imagery, the less she resembled the pretty, obsequious wife he’d married.

It’s not every young woman from the rural Deep South who’d trade in her doctor husband for life as an artist, but Ward did just that. In 1949, she enrolled in Black Mountain College, an experimental school near Asheville, North Carolina. For Cora Ward, Black Mountain provided an invitation to learn from other innovative artists and to build new friendships, one of them with the critic Clement Greenberg, who taught art criticism and modern painting and sculpture. From there, Ward moved to Chicago and studied at the IIT Institute of Design, also known as the New Bauhaus. She landed in Greenwich Village in 1955.

Ward paid the bills by working as a nurse. Her paintings turned up in solo and group exhibitions, but success came in modest measure, even while others in her circle won acclaim, made fortunes, and helped define an era.

After Ward died, two of her sisters flew to New York to settle her estate. They discovered 1,100 of her paintings and drawings stored in the building where she had lived. Most were in Ward’s small studio loft, but the sisters also found pieces squirreled away in the basement.

Ward had never remarried or had children. The art was her legacy and her gift to the world.

Photo: Mobile Museum of Art

Watercolor on paper, 1979.

The year 2020 marked the centennial of Cora Ward’s birth, and her work is finally being discovered and celebrated far beyond the region that produced her. Since the Hilliard sale, three of her paintings have sold at auction, and one of them achieved a hammer price of $1,000—not bad for a small canvas that the museum would’ve sold for six bucks. Larger examples have brought as much as $6,000 in private sales. And last year, one of her paintings hung in an exhibition at the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center called Question Everything! The Women of Black Mountain College.

In 2015, the New York Times published a photo of Ward in a story about the school, and two years later, her name appeared in news reports when a possible Jackson Pollock turned up in an Arizona man’s garage. The man had inherited the painting and other avant-garde work from his sister in New York. Images of the would-be Pollock, if authenticated worth no less than $10 million, were shown with other pieces from the hoard, including a canvas by Ward.

But such attention was still a long way off when Tim Miller approached me in the museum. “Well, what do you think?” he whispered. “Do I write the check?”

I didn’t know how to advise him. Earlier that morning, I’d looked for Ward’s name in several online art databases and come up empty. Likewise, a Google search had provided little. Ward had also been a photographer, and a website credited her for candid photos she’d taken of Clement Greenberg and her artist friends. But back then that was the extent of Ward’s presence online.

The credits put Ward on the scene, but they also suggested a remove. Why did she seem more like a witness to the party than a participant in it?

In the end, Tim and Dana bought ninety-three paintings. I chose twenty-one.

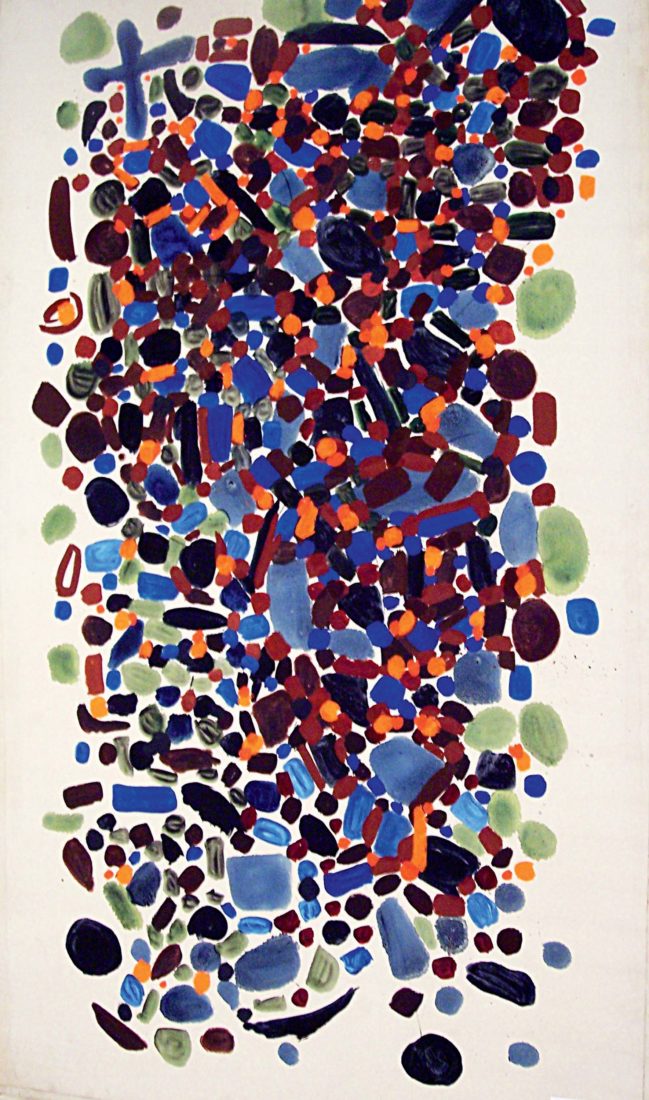

Photo: John Ed Bradley

Acrylic on canvas, c. 1970.

As I was carrying my load to the parking lot, a museum worker handed me a sheet of paper with an essay by Greenberg, written for a memorial exhibition that he’d curated the year after Ward died. Although they’d been friends for forty years, it was the only thing he’d ever written about her. Cora Kelley Ward’s art will last, he said, “as some far better-known art of this time won’t.”

Greenberg, who died in 1994, was arguably the most important art critic of the twentieth century. He’d given a powerful voice to abstract expressionism when most of the world thought it was a joke. If he truly thought Ward’s work had the potential to endure, why hadn’t he said so while she was alive?

What a shame, I thought. Cora Ward had devoted her life to making these pictures, and they’d been peddled in a fundraiser that would bring in only $10,919, for an average of $13.65 apiece.

“Do you think these things could pay for our kids’ college one day?” Tim said. He stopped me before I could answer. “A lady in there said she was going to use one as a rug.”

Somewhere on the road home that night, I pulled over to see how my cargo was traveling. As I raised the pickup’s bed cover, a semi blew by and dumped light on the pile of rolled-up canvases.

“Who were you?” I mumbled.

Not long after, I got on the phone and started calling people, the first of them Lee A. Gray, then the Hilliard’s curator.

Ward was like thousands of other artists who pursue a dream and in the end go unrecognized, Gray said. After receiving the collection, she sent five or six of Ward’s smaller, late-career paintings to a commercial gallery in New York. She wanted to gauge their potential value. “They said the colors were too seventies, too muted,” said Gray, who now works as an English teacher in Hungary. “They didn’t think the paintings would be popular with their clients.”

Photo: Mobile Museum of Art

Oil on linen, 1959.

It was the only gallery she contacted, although one of Ward’s brothers, Maurice Badon Jr., approached a gift shop in Hammond, Louisiana, the town where he lived. “They told me, ‘If your sister painted magnolias or antebellum homes, I could handle that. But abstract expressionism I don’t know about,’” Badon told me in 2014 (he died in 2017).

The Hilliard didn’t have enough storage space to accommodate such a large donation, and what to do with it weighed heavily on its director at the time, Mark A. Tullos Jr. After discussions with his staff, Tullos decided to offer Ward’s work to peer museums, among them major institutions in New York, all of which “turned them down flat,” Tullos said. “They all asked the same questions: What was her contribution to the movement? Why haven’t we ever heard of her?”

But other museums, particularly Southern ones, were not so dismissive. They liked the art, and they liked Ward’s story. The Mobile Museum of Art took seventy-three paintings, more than any other institution.

“I just responded to it,” said Paul Richelson, Mobile’s chief curator when I spoke with him in 2014, six years before his death. “She was clearly an artist of quality, and she did exhibit, she was in the mix, she knew the important artists of her generation. This is a very mature, very serious artist.”

Tullos spoke with Badon and floated the idea of a sale. Badon agreed to it. “The alternative,” Tullos said, “was to throw the art in the dumpster. I thought the sale was the best path. Let’s cultivate collectors; let’s teach. Even if they are paying fifteen dollars for a canvas, it gets the painting in their home. And they’re not going to Walmart and buying a reproduction.”

Photo: Alexandria Museum of Art

India ink on canvas, 1961.

Over the next several months, I talked to other art historians, dealers, and collectors. I visited the homes of two of Ward’s siblings. I called her old artist friends, one of whom spoke to me from Mumbai at two o’clock in the morning.

Why hadn’t Ward been bigger? Whenever I asked the question, Clement Greenberg’s name came up. Ward’s family and friends regretted that he hadn’t done more to get her work noticed. He had championed Helen Frankenthaler, his lover for five years before Ward entered the scene. Why couldn’t he have done the same for Ward?

“Clem was a complicated person,” said the artist Susan Weil. “He had people he got behind and made a big fuss over. That’s just the way he was. He wasn’t very generous in that way.”

One day Greenberg asked Ward why she didn’t give up painting and find a nice guy to marry. He might’ve been joking, but Ward took it as a rebuke of her work, and when she repeated his words to friends, she did so with a hurt look on her face.

“I think so, yes,” said Janice “Jenny” Van Horne, Greenberg’s widow, who died in 2015, when I asked her that same year if her husband ever had a romantic relationship with Ward. “But I also think I should’ve had you vetted before I agreed to this.”

Photo: Mobile Museum of Art

Oil on linen, 1961.

It was curious to me how my appreciation for Ward’s art grew as I learned more about her. At first dismissive of the pieces that depicted objects that looked like Easter eggs, I began to admire them once I understood that they were solely about color and referenced form as an afterhought. The paintings I liked best dated to the late 1950s and early ’60s and showed jots of color scattershot against mostly white backgrounds, rather like pebbles in a stream. In my office I taped a photo of Ward over my desk, there for when I needed a lift. The great American photographer Harry Callahan took the picture, and it dates to 1950, after Cora was liberated from Si Ward. She’s wearing a long coat over period clothing, dark hair swept back, lips parted. Her eyes are fixed on some point in the distance—far, too far away.

“What was she like?” was the first question I asked those who knew her. They almost all answered the same way: “Oh, she was beautiful.” And then they helped me build the picture.

At Black Mountain, a theater teacher was so taken with Ward’s striking good looks that he arranged the modeling session with Callahan. The teacher told her she could make it in the movies if the art career didn’t pan out.

She was as glamorous as “any Hollywood starlet,” said the artist Gene Hedge, with whom I spoke in 2015, and who died in 2017. Hedge first met Ward in Chicago in the fall of 1949. “My first impression was beautiful, interesting, and in another league.”

Ward stood just shy of five seven and weighed 120 pounds. She stayed in shape by walking and doing yoga. She read and collected books, and she wrote poems, stories, and at least one novel, none of them published in her lifetime. A perpetual student of her craft, she earned a master’s degree in art from New York’s Hunter College. One friend described her as a “seeker.” She might’ve grown up Southern Baptist, but she was open to learning about other religions. Late in her life she became enthralled with G. I. Gurdjieff, a spiritual leader who promoted a method for achieving higher consciousness.

It was always a jolt when her New York friends saw her wearing a nurse’s uniform. She was an artist, after all.

She drove a VW Beetle and liked good clothes and good shoes. In her kitchen she had a toaster with only one slot, suggesting she intended to live her life alone. And though her career as an artist never did rise to the conventional definition of success, she didn’t seem to care. Making the art was enough. Let her friends have the glory. She’d found bliss elsewhere. “There are no words to describe this feeling of wholeness which blooms in me … of being open to what is before me in great painting and drawing and sculpture,” she wrote in her journal while touring Aix-en-Provence, the city in the South of France where Paul Cézanne lived and worked.

When it was time to paint, she would tell her friends, “I’m going to be busy for two or three weeks. So I won’t be able to see you, okay?”

They knew not to bother her.

For all her hard-won sophistication, she was forever a small-town girl from Louisiana and given to sentiment when recalling her roots. When she had guests over for dinner, she often served gumbo.

Only those closest to her knew the details of her upbringing, much of it tragic. Her mother, Mary “Missy” Lavergne, had just welcomed a baby girl named Monia when her husband, Olite Rachal, died suddenly from an unknown ailment. The minister who presided over Olite’s funeral, Edward Kelly, was so struck by Missy’s beauty that he set out to win her heart. He would become her second husband.

Missy was pregnant with Cora when Ed Kelly was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

“There was a second little house behind the house where they were living,” said Jessica Balovich, one of Ward’s sisters, who died in 2019. “Ed Kelly moved out of the main house and into the little one. And then he put up a wire fence between the two. Mother would bring Cora out to see him, and Cora would put her little hands between the wires to feel his hands. That was as close as Cora ever got to her father.”

After he died, Missy put her two girls in a Baptist orphanage. “Mother had a calling to be a missionary, but she needed an education and she had no way to support them,” said Ward’s brother Maurice.

Monia Joyner, formerly Monia Rachal, was two days shy of her 103rd birthday when she died this past October. “Over the years, whenever I’d see Cora, we’d bring up the orphanage and talk about it a little bit and then just drop it,” she told me in a 2014 interview. “It was painful, but I think the experience hurt Cora more than it did me.”

The girls were reunited with Missy only after she married Maurice Badon, a fellow student at the Acadia Baptist Academy. The couple would have five more children, and Missy always insisted that all seven kids be treated the same, even though Monia and Cora had different fathers. After high school, Ward left for New Orleans. She was working in a hospital when she met a young ob-gyn from South Carolina.

“Si was a tall, thin fellow. Wry sense of humor. Had that accent they have out there. A-boot instead of about,” said Ward’s brother Maurice Badon Jr.

Photo: Diana Woelffer/Collection of Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center

Ward at work at Black Mountain College near Asheville, North Carolina, in 1949.

They married in 1941. After Si returned home from serving in the war, Cora told him she didn’t want to be his wife anymore. He accused her of cheating on him. Cora denied it. Si arranged for her to see a psychiatrist with experience in relationship therapy. After meeting with Cora, the man told Si to let her go. Nothing was going to stop her from being an artist.

“Si didn’t want her to be an artist. He wanted her to do exactly what he wanted,” said Cora’s sister Jessica. “He was very controlling, and she was so artistic. Cora was lovely. She never would’ve been unfaithful. She tried with Si, she really did.”

The divorce came in 1948. The last time Si saw her was when she boarded a train bound for Black Mountain. “Si threw a fit,” Jessica said. “He said the people there had loose morals and all that, and he tried to get us to stop her. But it was over, and she didn’t have to answer to him anymore.”

Photo: Marianna Massey

Two of Ward’s paintings on display at the Hilliard Art Museum in Lafayette, Louisiana.

OLD CENSUS ROLLS show the spelling of her father’s name as Kelly, but Ward insisted on signing her canvases Kelley.

“Oh, no,” her brother Maurice told me. “You didn’t want to leave out that second e. Cora was very particular about that.”

Every summer, family traveled to New York and stayed with her at her studio. Ward returned home when she could, at least once a year.

“She always wanted us to think she was doing well,” said her sister Monia. “But I didn’t understand her art. I remember saying once, ‘Cora, why don’t you paint me a duck or something?’ I saw the look on her face and didn’t go any further.”

Ward once told Gene Hedge about the wire fence that had separated her from her father. Hedge wondered if it explained why Ward was such a solitary soul. She only grew more reclusive as she got older, and she refused all visitors once she realized she wasn’t going to beat cancer. One of her sisters, Vivian Greene, flew up from Houston. “Cora, please!” Vivian called out at Ward’s door. Ward refused to let her in. Vivian returned to the airport and flew home.

Photo: Mobile Museum of Art

Watercolor on paper, 1960.

One day Hedge walked over to Ward’s place with the artist couple Susan Weil and Bernard Kirschenbaum. They knocked on the door but got no answer even though they sensed Ward was inside.

Hedge slipped a note expressing concern under the door. His phone was ringing when he got home. “I never heard her speak in anger except that one time,” he said. “‘Leave me alone!’ And that was it.” Hedge didn’t return to the apartment until after she died.

“The paintings from her friends that had always been on display were down on the floor facing the wall,” he said. “Her own work, too. You didn’t see any painting at all. So she had cleared out her life.”

A short time later, Clement Greenberg arrived at the studio to see the work. Hedge had a key, and he let him in. “Clem had visited her studio before,” Hedge said, “but there was a lot he’d never seen. When he looked up from the art, I could tell how moved he was.”

“Cora was a dear & selfless friend,” Greenberg would write later. “But I can confidently say that that doesn’t sway me. It’s only with these paintings of the ’80s that I’m able to hail her art without reservation. That makes me glad—regretfully so because she’s not here to read what I write.”

After Ward’s ashes were interred in a New York cemetery, her sisters Jessica and Vivian visited Greenberg at his apartment. “I told him, ‘You didn’t help Cora one goddamned little bit, Clem,’” Jessica said. “Clem said, ‘I thought you were a Baptist and didn’t curse.’ I said, ‘You’re the only person in this whole world I would say that to.’”

Hedge told me he often remembered something Ward asked him toward the end, when her interest in spiritual matters intensified and she was spending less time making art: “Is painting still enough for you?”

“Yes,” he answered, and then tried to explain why.

Ward didn’t reply, but Hedge understood that she didn’t need to.

OVER TIME, I collected thirty more of Ward’s paintings and twenty-seven more drawings, putting the total at seventy-eight. My wife cut me a look every time I came home with another one.

Many who’d bought her work from the Hilliard refused to sell. They said her paintings had become part of their lives and they couldn’t imagine living without them.

One day I stopped by the sprawling manse in Lafayette where Tim and Dana Miller live with their three young children. Tim and I were standing beneath chandeliers in the formal living room, and Ward’s work decorated the walls. I pointed to a massive canvas and offered him $5,000 for it.

“Not a chance,” he said.

I pointed to an even larger canvas. Ward’s carefully placed colors seemed to dance from one side of the painting to the other.

If only you were still with us, Cora, I thought, we could tell you how wonderful we think you are.

“Twelve,” I said to Tim, the word so dry in my mouth I could barely get it out. “Twelve grand. Come on, old man. Sell it to me.”

Less than three years had passed since the Hilliard sale, and the price was $1,081 more than the museum had earned for its entire inventory.

Tim lowered his head. “Can’t,” he said. “I’m sorry, brother, but I just can’t do it.”