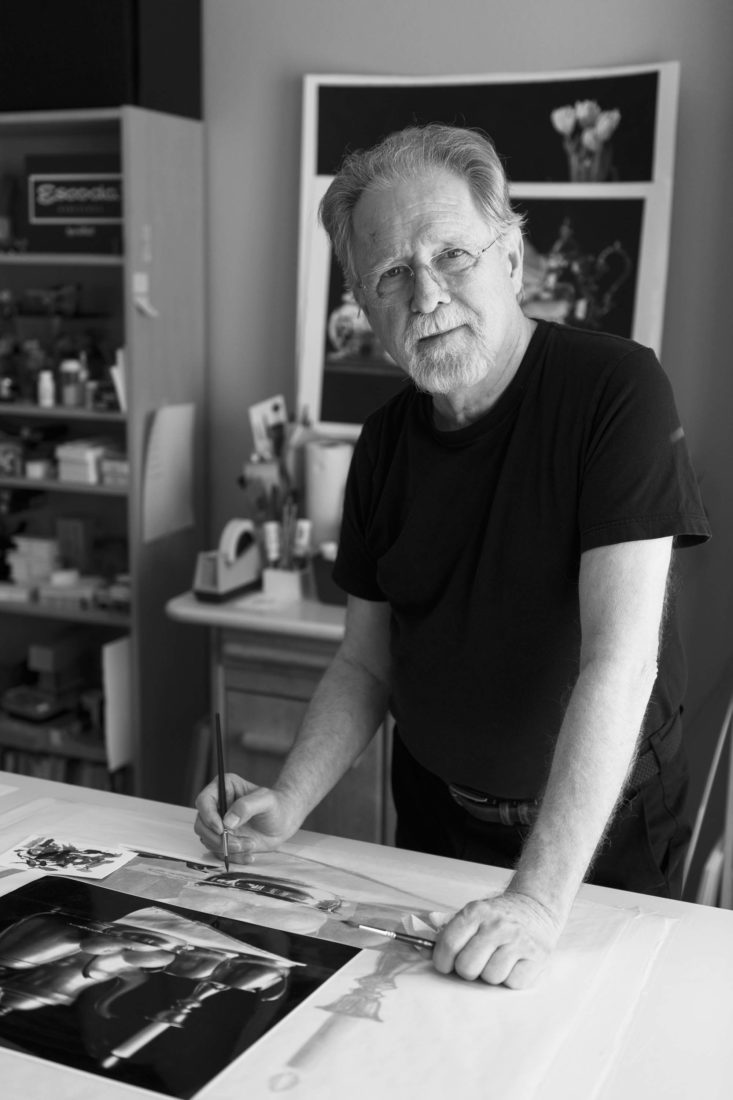

Laurin McCracken dabs his paintbrush into a lukewarm jar of water, then into one of the five different shades of black he has on his palette. After testing the color on a scrap, he takes the brush to the three-hundred-pound soft press Italian paper on his desk and makes four or five smooth, delicate strokes. “You can see the water soak into the fibers of the paper,” he says, his native Mississippi brogue apparent in every word. He’s about halfway through a still life: three blazingly bright clementines and a matte pewter tea set on a folded white cloth. Thin layers of tracing paper, secured with tape, protect most of the piece in progress, leaving only a small section exposed.

That’s how McCracken works here in his Fort Worth, Texas, home studio: one minute detail at a time, creating paintings so vivid they seem closer to photographs. The lines at the edge of his Ball jars look so crisp, the shadows so stark. The crinkles in folded foil, the gleams of light reflecting off silver: All temporarily trick the human eye. In a piece he just finished, an image of loose silverware for sale in a water-stained cardboard box, blue sky reflects in the curves of spoons and knives.

McCracken, startlingly enough, didn’t start painting until later in life. After a successful career as an architect, a watercolor class he took at age sixty while living in Virginia transfixed him, and he went on to take classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. “Architects and watercolorists have a lot in common,” he says. “It’s about strategy and planning. I love breaking something down into accomplishable pieces that add up to something beautiful.” McCracken, now seventy-eight, has done just that to create his still lifes: glass jars, silver teapots, antique toys, vintage typewriters, old cigar boxes. He captures the beauty of a bygone era. When he began, “nobody was painting silver and nobody was painting glass,” he says. “I saw these things and thought it could be a modern-day Dutch still life.” Curators agree: Galleries, museums, and exhibitions in North America, Europe, and Asia have hung his work.

One painting can take McCracken more than a hundred hours. His process starts with a camera: He’ll arrange and photograph a composition that interests him, print his chosen image in high definition, and then project the picture onto the wall upstairs so he can trace it onto the thick Italian paper. Then he systematically replicates the color and shading of each tiny sliver.

To demonstrate how he gets his brushes to form such a fine point, he wets one, then flicks it toward the floor. When he brings the brush back up, the tip is sharper than a freshly shaved pencil. The key to keeping the white so bright on, say, a piece of reflecting glass or silver, is not painting it at all. He instead uses masking liquid to cover up those areas when he’s working, then removes the mask when he’s done.

His rapid ascent in the art world stuns him at times. “My retirement is more fun than my career,” McCracken says. “I’m the guy who gets up every morning and pinches himself.” Back in his studio, he touches his wrist to the paper to test the dampness, then adds a few more strokes of shading to the pewter bowl—creating a new reality, one tiny element after another.