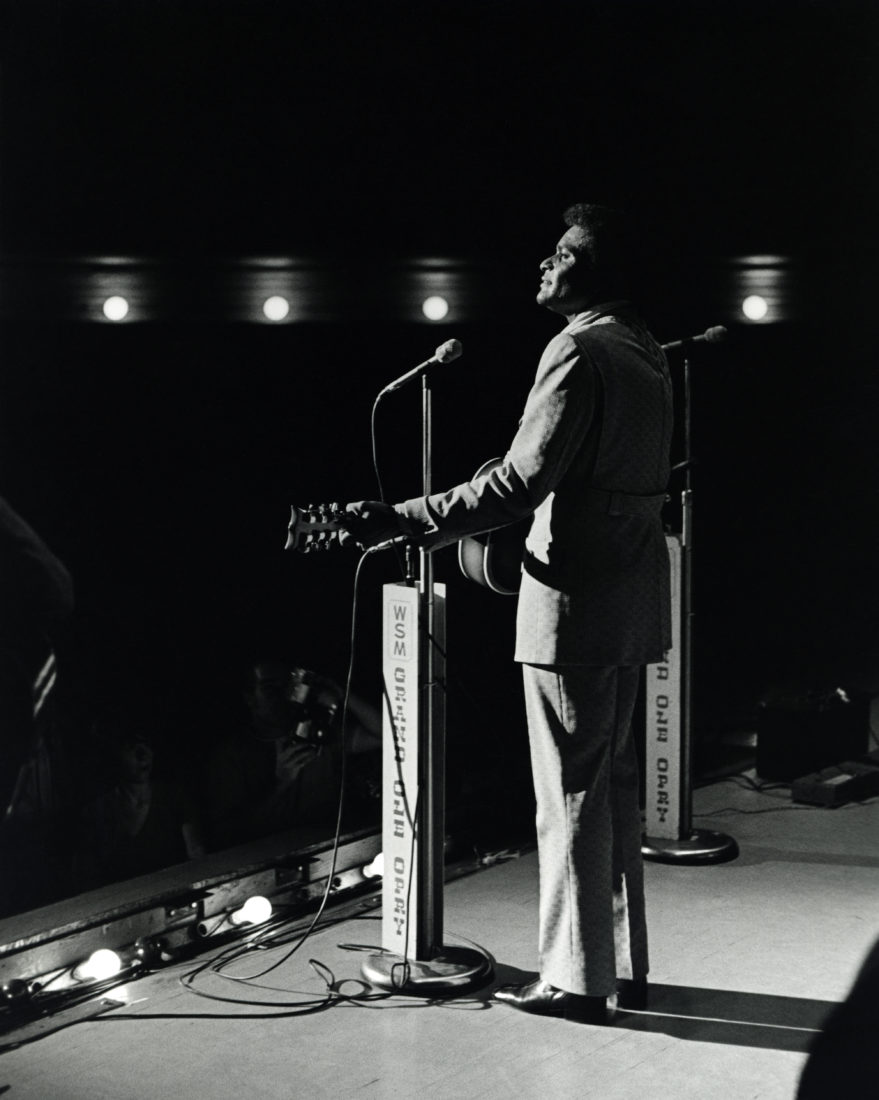

This weekend, the Grand Ole Opry, the world’s longest-running radio show, will host a record-breaking 5,000th Saturday night broadcast. And even though I live in Nashville, where sometimes it feels like country music swirls in the air like whispers of ghosts and sticks on your skin like dew, I’ve never considered myself an Opry buff or an aficionado of the genre.

That’s part of why I surprised even myself when I came across a television broadcast of the Grand Ole Opry early in the pandemic and listened with rapt attention. On March 21, 2020, Vince Gill, Marty Stuart, and Brad Paisley took the stage and faced the echo of more than 4,000 empty Opry House seats—the first time I’d witnessed such a thing in lockdown. Like most of America that evening, I was home on that Saturday night with a newfound anxiety about what we were all going through: sudden job losses, restaurant closings, growing food insecurity, a mysterious illness, death, and the unknown of how long we could keep this up. Then Stuart sang “No Hard Times” and before long I was crying.

“Country music is no stranger to hard times,” Stuart said that night, holding up a guitar that belonged to Jimmie Rodgers, the man who wrote and performed the song in 1932. “And the Grand Ole Opry is no stranger to hard times. Ninety-four years old, world wars, catastrophes, presidential assassinations…somehow the show has always just gone right along. Almost never gone off the air.”

True—despite the Great Depression, World War II, multiple Nashville floods, and all manner of struggle, since 1925, the Opry has consistently gathered a large swatch of America around their radios (and now television sets) to offer a place to escape, mourn, rejoice, or hope. It reminded me of a story Stuart shared several years earlier about listening to the Opry as a young boy sitting on his grandmother’s lap in Mississippi. During one particular broadcast, the performers held a moment of silence for Patsy Cline, who had recently died, and Stuart could hear the sniffling of audience members three hundred miles away. I loved the tale when he told it, but watching and listening during the pandemic, I felt like I understood more fully that moment of collective grief.

Years after Cline’s death, Dan Rogers, now the executive producer of the Grand Ole Opry, made his first visit to the institution as a four-year-old to see Dolly Parton. He listened to the show his entire life, often from the back seat of the family car wherever they happened to be driving on a Saturday night, and in 1998 he started an internship at the Opry. He’s been there ever since. As for this weekend’s milestone broadcast, he makes no secret about the fact that broadcasts could have been skipped in the 1920s, 1930s, or 1940s, back when it wouldn’t have been heresy. But he only knows of two cases for sure. One of them happened when Franklin Delano Roosevelt died, and the radio went silent out of respect for the president. The Opry held a live show, but didn’t broadcast it. And then later, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., “kind of the opposite happened,” he says, “in that there was no live show due to a Nashville curfew, but they played a rebroadcast. In both cases, respect was paid, but also in some way, the Opry still managed to find a way to play on respectfully.”

During Rogers’s tenure, the challenge of consistency has meant finding a way to keep the show going even when the Cumberland River rose several feet above the stage in the March 2010 flood. Still, that disaster paled in comparison to the pandemic. The flood, while difficult, he says, had a beginning, a middle, and an end. A community rebuild toward a common goal ensued with a target open date in mind. “In the case of the pandemic, there was no looking at the calendar.” Rather it was a day-by-day recharting of course into the unknown. “I’d say there was little more challenging or emotional than watching artists, who in some cases hadn’t left the house in a month or so, coming out and sitting or standing on the Opry stage and being pointed to when seven o’clock rolled around, and singing their hearts out for people tuned in from around the world—but no one looking back at them from this empty Opry house.”

Vince Gill remembers that feeling from March 2020—it served as a powerful reminder of the Opry’s early days, when musicians played in a Nashville hotel room for no live audience. “You’d finish your song and there was nothing,” Gill says. “It was actually kind of beautiful. You knew the response was not going to be something you could hear, but that it would probably be something that people would feel on the other side of it.”

Gill has a way of looking on the upside, too. “We’re at our best, I think, during hard times,” he said during that March 2020 show. “As sad as these times are that we’re kind of going through right now, the silver lining, the beauty and the blessing in all of it, is that we’re all kind of gathering around our families and gathering around people we love, kind of circling and finding our way through.”

Now, more than a year and half since that show, he explains more about what he meant. He acknowledges a deep appreciation for melancholy and the blues, and notes the faith that springs from hard-time tunes in the church. “Music is always in some kind of way mirroring our experience, our history,” he says. “And so music has always been a great place for me to go for emotion. Whether there’s a bunch of people in that room or nobody in that room, I’m gonna play and sing the exact same way. I’m always playing for me, and I hope that it translates.”

As shows continued from an empty Opry house (and for millions at home), Rogers kept gathering stories. The time, for example, when Ashley McBryde, Lauren Alaina, and Terri Clark got out of their vehicles and stood at a tailgate more than six feet apart to run through their show on a beautiful spring day, alone in the parking lot.

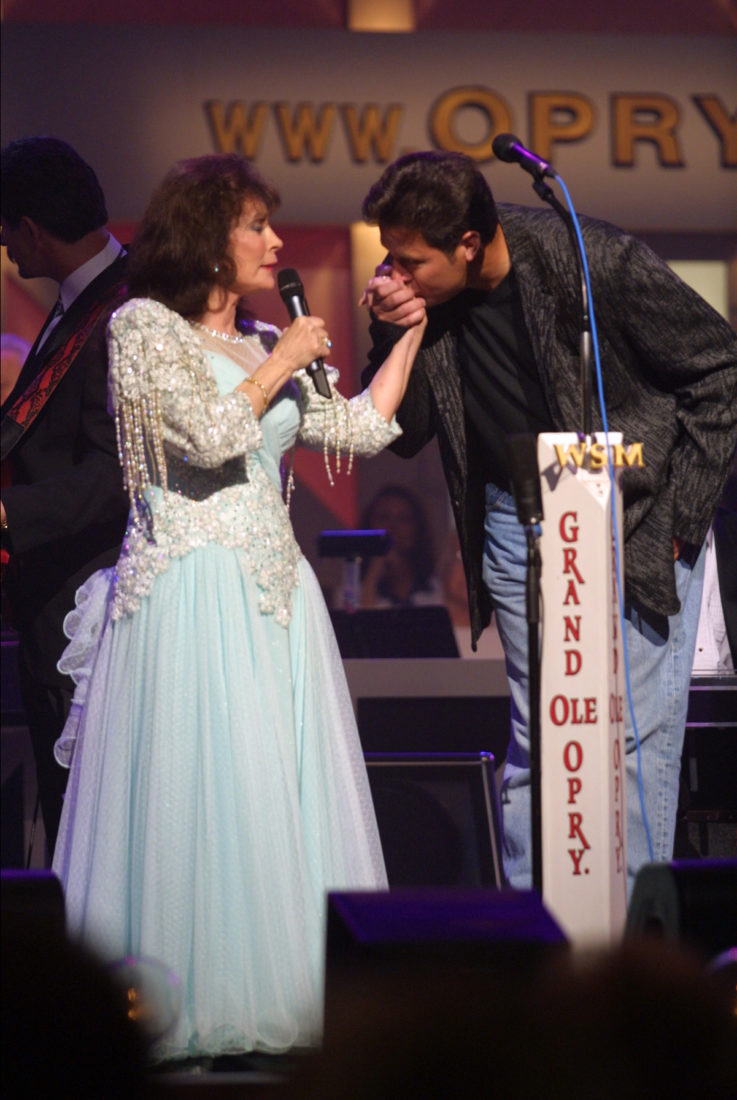

Meanwhile, he received a growing number of texts as those pandemic broadcasts aired. “We set an alarm clock,” people would tell him. “We knew we could watch it later, but we wanted to watch it live as it happened.” Those messages reminded him of stories from the early days of radio when folks would walk to the neighbor’s house to listen together—and sometimes play along. It made him think of Loretta Lynn, who grew up in tough times when the radio only came on for important news and on Saturday nights for the Grand Ole Opry.

Rogers also recalls the moment a bluegrass band came in about five months into pandemic. “I remember sitting in my office and hearing instruments playing together again,” he says. “A fiddle, a banjo, a guitar. And just thinking how amazing that full, happy sound was, and that, had it been six weeks earlier, I would have completely taken those sounds from a rehearsal area for granted. Hopefully that was one of many, many reminders of things to try to never take for granted once we are beyond this pandemic once and for all.”

While making it to this 5,000th broadcast never came into question for Rogers, he says the milestone still feels like a victory. The lineup includes seasoned folks joining those from the Top 40. Garth Brooks and Trisha Yearwood will be there, along with Darius Rucker, Terri Clark, Chris Janson, Jeannie Seely, Connie Smith, the Gatlin Brothers, and Chris Young. Rogers says Bill Anderson will open the show with “Wabash Cannonball,” a tune Roy Acuff made famous on the Opry stage. Gill, meanwhile, says he will nod to history by playing a guitar once owned by Sam McGee, a longtime Opry player with his brother, Kirk McGee, dating back to 1926. Otherwise, he says he’ll probably decide what else to play closer to the moment.

“It’s neat, but we have a funny way of rounding off certain anniversary-type things,” Gill says. “The 4,999th is just as important as the 5,000th. To me, they’re all the same and all beautiful. They all had a point and moment in time.” And as the Opry has become a cultural institution over nearly a hundred years, those moments often meant something to someone—whether listening in grief at home or in the collective effervescence of a live show, no matter the milestone.