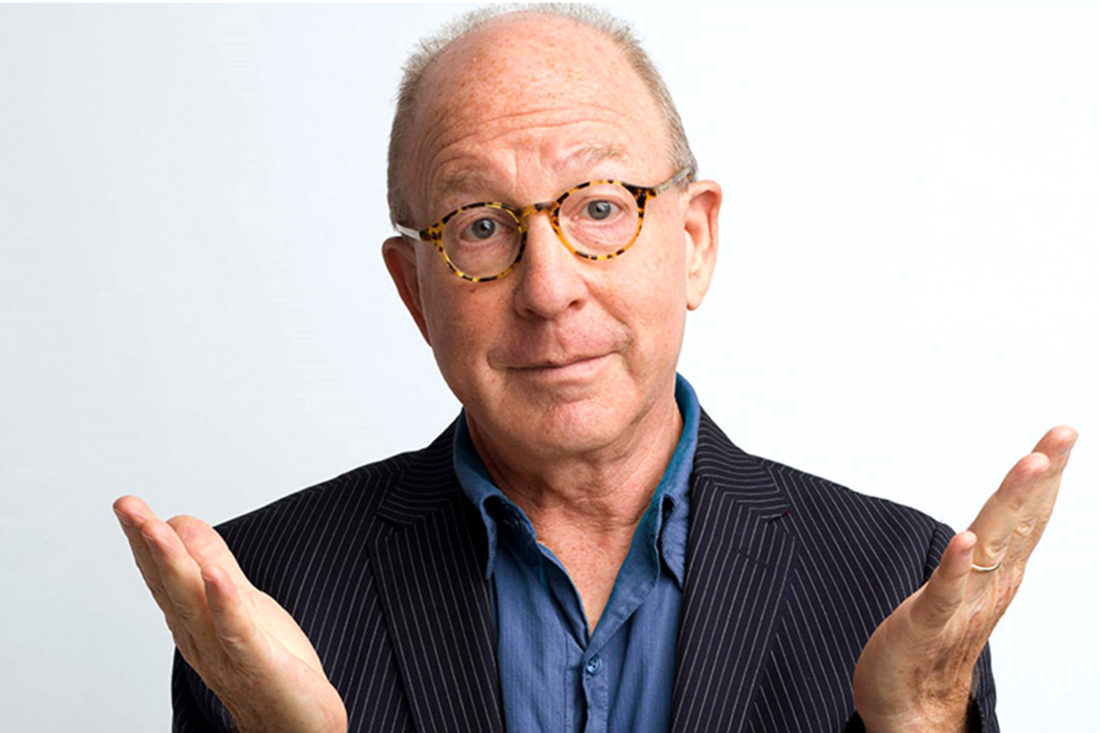

“You could go to the greatest museums in the world and see a Rembrandt and go, hmm that’s kind of brown,” says the seventy-one-year-old art critic Jerry Saltz. “Or you could just go to a museum looking for all the naughty bits. The point is, it’s not possible for all the art you see to be good. And you’re not going to like most of it.”

Saltz, who won a Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 2018, is interested in what he calls art that is “in play.” And he sees a lot of “in play” art coming from the South. “I mean that it’s visually convincing, that it has something believable about it without any explanation. I do not have to like the work, I just have to say to myself, people should see this and hate it or like it.” And he encourages people to talk about what they think with honesty.

When Saltz travels to Charleston, South Caroline, in November to speak at the Gibbes Museum of Art’s Distinguished Lecture Series, he’ll be returning to a land he loves, a place he first understood through a truck window (he tells that story below). His personal and entertaining new book, Art Is Life, comes out November 1. Here, the author shares more about how he came to love the South, his quite entertaining Instagram account, and why he thinks there should be a more fitting term for some of the greats than Southern artist.

How did you come to know the South?

I was a long-distance truck driver for about ten years. I drove once a month from New York to Texas or New York to Florida, so I spent many, many, many days, months, and hours in the South and absolutely loved it. I kept thinking this is real America. As someone from the Midwest, I too come from America. I’m a son of the Great Lakes, but New York, where I live now, sometimes seems like this small island off the coast of the United States that flies a pirate flag and thinks it’s the center of the world. I spent many happy nights and days being miserable in my truck, but I loved being in the South. Parts of it are as busy and crowded as any city, and between the cities there’s awful traffic, too, just like awful traffic anywhere. The good architecture and the crap architecture. The losing sports teams, the winning.

But the South is not just a place; it’s a great kind of cathedral of the mind of America. It’s one of the most important sources of all our great art. It’s a miracle the literature, the music, and the visual art that pours out of that place despite its problems. It’s insane if you think about it—genres are not born that often. Sometimes centuries go by and it’s like, oh the novel! Oh landscape painting! Those are genres. But in the span of what, one hundred years, blues, jazz, Southern gothic, all these genres were born in the South.

Where do many of the most powerful women artists come from? The South. While the men of blues and jazz might have been leaving home because it wasn’t possible to succeed as a bread winner, what we forget is the women stayed home and created this little thing we call Southern literature. A little thing that we call some of the greatest two-dimensional art this country has ever seen in the form of quilts, embroidery, paintings.

Who are some of your favorite Southern artists?

Clementine Hunter. Bill Traylor, probably the greatest American artist the twentieth century produced. I could make the case that Traylor belongs with the greatest of all of them. Yes, we call them “outsider artists,” but they had a studio practice. They showed their work, they sold their work, and in a way, they had the same story that Van Gogh had. Van Gogh was a poor and famous artist in Paris. Every artist knew what he was doing, in the same way Traylor might show his work on the sidewalk, his work was appreciated and the people around him knew that this was an American visionary. You talk about Southern artists, you’re talking about Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Kara Walker, Nellie Mae Rowe, Thornton Dial—I could go on and on and yet whenever we talk about Southern artists, there’s a tragedy that happens. We use the phrase Southern artists. Instead of artist. Imagine if every time I talk about your work, I said female writer CJ Lotz.

We’ve cursed ourselves into this trick, this regional thinking. It’s a curse because it locks people into one way. God knows we do that with outsider artist. Clementine Hunter? Great painter. Artist. It’s all there in the work.

How did you get into art?

I began as an artist, and I was somewhat successful. When I was younger, I sold my work, my work was reviewed, I got a National Endowment for the Arts grant, and I took that money and I moved to New York, and I lived in a fifth-floor walkup of a drug dealer’s building that had guard dogs living in the hallways. I had no heat, and I was ecstatic, living in a shithole. I was going to be an artist. But then demons spoke to me. The same demons that speak to all of us at 3:15 a.m. As someone who never went to school, who has no degrees, and was desperate to be in the art world, I listened to the demons, and I stopped making art. I self-exiled.

That is the ten years I spent driving. One hundred percent alone on the road, living an enormous lie. I was filled with hatred and envy because I delivered expensive art to rich collectors and famous galleries and I became so bitter and angry at everyone else, thinking everyone else is worse than me but everyone else is doing better. I was eaten alive by this. And one day I thought, anything is better than this. I had never stopped going to art galleries, and I thought I had to be back in the art world or I would die.

It’s a long story. [The full story is in Art Is Life. It’s funny and involves a Texas art collector, Saltz simply telling people he was an art critic, and meeting his now-wife, the critic Roberta Smith.]

I wrote my first review at age forty, and it didn’t matter that I was crap. I knew I was finally failing in public, and that I had to try to be radically vulnerable. As radically vulnerable as I felt on the inside as I feel that all artists are on the outside. In 2018, when the Pulitzer Prize people called me and told me I had won a Pulitzer for criticism, I was sitting in the same office that my wife and I rent year-round, and we hugged. My wife is a far better critic than I am. She should have won that prize. But the point is, and all writers will understand this, that within an hour of being told the news, my wife and I were back at our desks, writing on our deadlines.

I have spoken to people who have won Pulitzers and Nobels, and the most comforting thought for those who have the drive to dance naked in public—like all artists and writers are actually doing—the greatest comfort I had was that week, I kept thinking, well they can’t fire me now! For about eighteen more months! Now I worry every day again. I’m overachieving, like all artists and people who make things.

How do you approach looking at Instagram, and how do you choose what to feature?

I call myself a hashtag archeologist. We’re all watching this light and color and speed and everybody else’s lives and thinking, how come I don’t go out? How do they do this and that? I’m scrolling. In the morning when I’m worrying about writing, I’m death-scrolling, and when I see something I like, I go, huh her work’s okay. And now this takes a millionth of a second, but I’ll see she posted another person’s work and I’ll look there and then there, and I’ll click and then all of a sudden there’s an Andrew Lamar Hopkins!

You’re referring to the New Orleans artist Andrew Lamar Hopkins, who is about to have his first solo show in New Orleans. What drew you to his art?

It’s way outside expectations. People should see it. It isn’t stuck in the trauma narrative or the pain fetish of art. His art is about life lived in peacock glory, dazzling, crazy, and it has this great sexuality. It generated a huge amount of interest on my Instagram.

I do have two rules on Instagram. One, you may call me anything you like. You could never say anything worse about me that I haven’t already said about myself today. But you may not call anyone else in this thread a name. I’ve watched people attack each other, and no. I’ll block you. Two, I don’t like cynics. People with the attitude of, I know why she really got this job. Her parents are rich. No one knows what each of us live through to get here.

What do you hope people take away from Art Is Life?

In the twenty-first century, I had this accidental and intentional front row seat to every single thing coming down the pike from 1999 to 2022. None of this art was made under normal conditions. War, the rise of mega-galleries, the pandemic, where everything went back indoors to this cave-like condition of people making art out of what was at hand. Your room was also your work, your studio, your family, we were all living back in the cave. The very center of all of our DNA, creativity itself, was thrown into question. Art history is being rewritten right now, and this book covers that.

Right now, more underrepresented artists are taking the stage, rightfully. More women, more artists of color are becoming the centers of the market. Some cynics might say that more mediocre work might get through as we’re rushing to make sure this group of people is accounted for, and this and this. But that’s no different than all the mediocre male artists that have ever gotten success at first. Art history will sort it all out. Of course, 85 percent of any art being made is always bad. But then you get one Kara Walker out of Atlanta? One artist of that power is enough to change a nation.

Find more about Saltz’s lecture in Charleston here. Here, find his books Art Is Life and How to Be an Artist.