In the West African country of Côte d’Ivoire during the eighties, Peter One was a household name, playing his country-folk music to stadiums full of fans. But after political unrest at home led him to emigrate to the U.S. in the nineties—first to New York, then Delaware, then finally settling in Nashville—he was known to friends simply as Pierre, a soft-spoken, middle-aged man who worked as a nurse, wearing scrubs and attending to the needs of the sick and infirm.

Now, the sixty-seven-year-old singer and songwriter is finally reclaiming the musical legacy he began four decades ago halfway around the world. A 2018 reissue of his 1985 collaboration with his friend and fellow Côte d’Ivoire musician Jess Sah Bi, Our Garden Needs its Flowers, brought the opportunity he’d been looking for since he arrived in the U.S. decades earlier.

Out in May, One’s debut solo album, Come Back to Me, is stacked with songs he wrote during his sabbatical from the music business, characterized by his unhurried, supple fingerstyle guitar playing and vocal melodies that split the difference between his heroes Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and the Cameroonian crooner Eboa Lotin. Collaborators on the album include Pat Sansone of Wilco and Allison Russell, who duets with One on the album’s closing song, “Birds Go Die Out of Sight.”

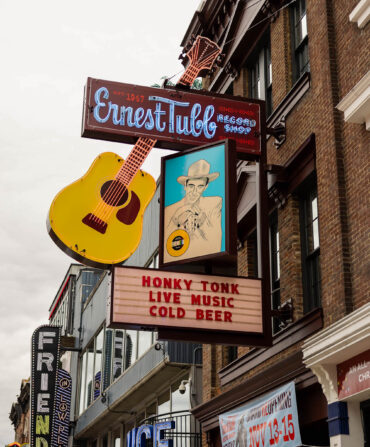

Although One still has his nursing gig as a backup plan, Come Back to Me just might be his ticket back to stardom—and this time, not just in his homeland. Recently, he’s been opening shows for Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit, and he makes his Grand Ole Opry debut tonight.

We caught up with Peter One while he prepped for his second bid for music stardom.

Did you plan to put your music career on hold when you came to America?

Oh, no, I did not. On the contrary, I was planning to continue even further as soon as possible. But when I came here, reality hit me [laughs]. I knew it wasn’t gonna be easy.

That whole time, as you were building a career outside of music, you had memories of playing stadiums back home.

Sometimes it was a little bit hard. Some people ended up knowing about me, without me telling them anything. But I didn’t want to tell people because I had nothing to show them. I don’t like talking; I’d rather do it.

“African Chant” from your album with Jess Sah Bi was used in media coverage when Nelson Mandela was freed in South Africa in 1990—easily one of the defining moments of the late twentieth century. What did you think at the time?

Happy, and at the same time, [wondering] why did they choose my music? Only God knows, but I feel like I did the right job, maybe, because the song is about Africa: Keep fighting for your rights. Don’t think about revenge; stay tolerant. These are the [ideas] that touched them when they picked the song, maybe.

How big did your music get before you left Côte d’Ivoire?

Before the record came out [in 1985], we were just known around Yamoussoukro, the capital city, in the musician community, and with people who love music. We were doing some radio shows and TV shows. When the record came out, people knew us all over the country and the region. We played a lot of great shows. We even played before many African presidents.

And yet you still had to start over, financially and otherwise.

It was good, but musicians, they get a lot of money, but they spend a lot. When people see you on the TV today, the next day you’ll find ten people at your door asking for something. Like you came back from the TV station with a million in your pocket [laughs].