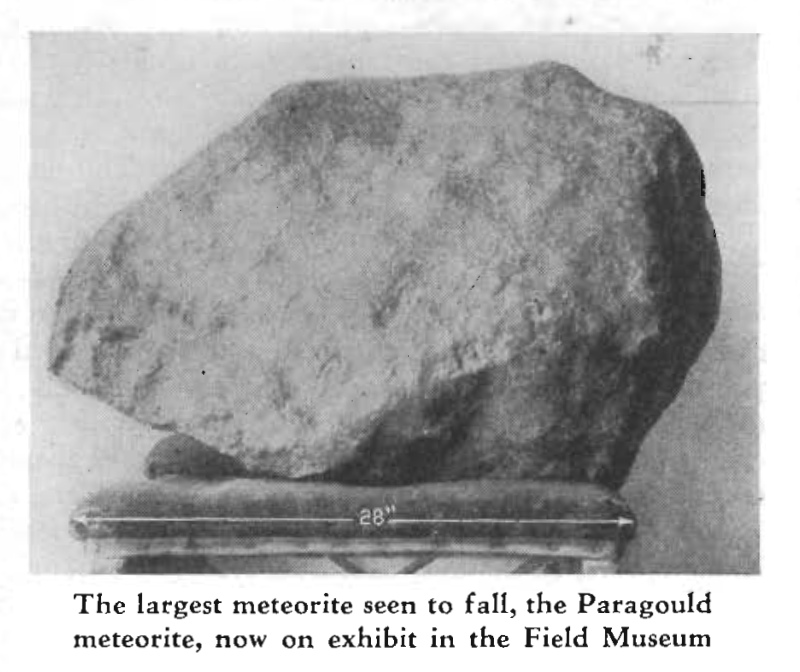

Here’s how the story begins. In the March 1931 issue of Scientific American, the magazine ran an article titled “Largest Meteorite Seen To Fall.”

“At about 4:08 a.m. on the morning of February 17, 1930,” wrote Charles Clayton Wiley, an associate professor of astronomy at the University of Iowa, “a brilliant meteor appeared over southern Indiana, first attracting attention when nearly in the zenith for persons living near Evansville. It fell to the south-west, following approximately the direction of the Ohio River, crossed south-eastern Missouri and at a height of about ten miles near Paragould, Arkansas, it burst into three main pieces.”

For roughly ten seconds across seventy-five miles, night turned into day as though a switch had flipped as the meteorite—between four and six times the size of the full moon—filled the sky. Onlookers looked up and saw bursting rockets, balls of fire with tails ablaze, bad omens, and the End of Days. Despite being visible across three states, Wylie wrote, it “gave everyone the impression of being very close.”

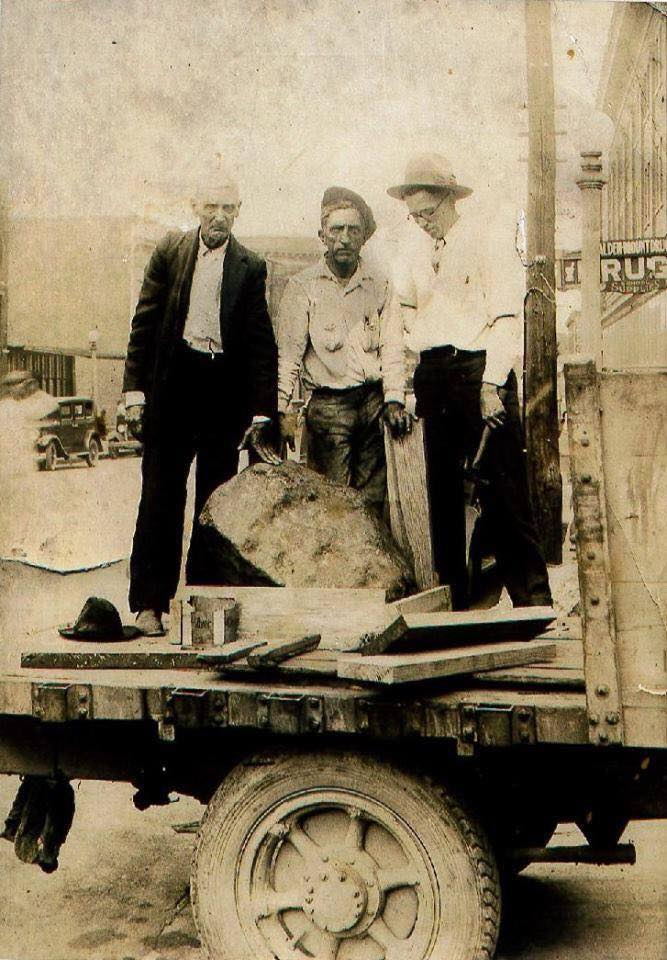

Entering the earth nearly vertically, the largest piece drove eight feet into the ground, scattering clods of clay more than fifty yards across the pasture where it landed. Although the smaller of two stones was discovered the next morning (the third was never found), it would be nearly a month before a farmer living a few miles southwest of Paragould in the community of Finch, W.H. Hodges, spotted the hole on land belonging to his neighbor Joe H. Fletcher on the morning of March 16. After a half hour or so of digging, the two succeeded in bringing the 820-pound stony meteorite to the surface. Not long after, Fletcher sold the meteorite to Harvey H. Nininger, an amateur meteorite hunter (now widely known as the father of the science of meteoritics), who then sold the meteorite to Stanley Field of Chicago’s Field Museum fame.

It would take nearly a hundred years before the meteorite returned to Greene County, where it lies today.

The reason why that matters is another story entirely.

After the meteorite was shipped up to Chicago, that was it. Joe Fletcher was some $3,600 dollars richer. There were some simmering squabbles as to who’d found what and when, and who deserved a finder’s fee and how much, the upshot of which were a handful of hurt feelings and at least one bloody nose.

It’s true that there were a few chips of the meteorite floating around town—by the time the main chunk was weighed at the Field Museum, the originally claimed 820 pounds had dropped to 745, “lost to souvenir hunters and through other causes,” according to a museum bulletin—but for the most part, the most tangible aspect left in Paragould beyond the deep craters in the earth was the feeling of an absence where the meteor had once been. That, of course, and the stories.

Stories had started circulating as soon as first light hit. As people sought out their animals that had gotten spooked and broken loose from their pens the night before, accounts were shared, tales expanded and embellished, beginning a sprawling game of telephone. (The irony of course being that this was a rural area, not especially well-off, and there were no actual telephones to speak of.)

Nearly a century later, such stories still circulate among families lucky enough to have storytellers in the genetic mix. When you hear these tales—about who did or did not help dig up the big rock and the little rock, about pieces that grandfathers chipped off the old block for future generations, about a baby born on the same day—it’s clear they’ve been worn smooth by generations of tellings, edges burnished like river rocks.

Take, for example, the story about the rooster.

“You don’t know about the rooster? Oh my goodness,” says Doris Hagen, president of the Greene County Museum. “Well, the cows and horses and pigs and the dogs and the whatever all ran away or tried to find a place to hide. But the story goes—this could have been a Grandpa one—that the only critter that didn’t run was the rooster. In fact, when he saw the flame in the sky, he thought it was the best sunrise ever and almost crowed himself crazy.”

At family gatherings, Hagen says of her youth, after the meal had been finished and her grandparents had doled out pieces of their famous peanut brittle, her grandfather, Tellas Treece, would hold court from his chair, telling the story of the meteorite. Although Treece had been among the folks who’d nicked pieces for his kids, to hear Hagen tell it, it’s clear that the stories meant far more to him than anything else.

“I think he appreciated the fact that he was alive at that time, and he could witness this thing from, you know, billions of years ago come crashing down,” Hagen says. “It must have meant more than [just] something to talk about. Because it was important to him to not let it go. When you know [for] so many others, when it was out of sight, it was out of mind.”

“If I were to write a comprehensive history of Greene County, the meteorite would be just one chapter—it’s not the entire book,” says Erik Wright, a local author who’s written extensively about the area and is currently at work on a book about the meteorite. “Because we have a lot of history before the meteorite, and we have a lot of history after.”

The simple truth is that terrestrial matters outweighed the cosmic.

The stock market had crashed just a few months before, in October 1929, and whatever sense of economic stability the area might have otherwise known had been sapped dry by the Great Depression. There were children to feed, debts to pay. It should come as no surprise, then, that one of the few people living who can still remember the meteorite’s fall, Bernita Rogers, recalls being impressed not by the rock but by the windfall that the Fletchers got in exchange.

Even in stories like Hagen’s, there are hints that, in the years that followed, the meteorite slipped into the backdrop of daily life, tumbling down the hierarchy of resident needs and daily obligations. Although her grandfather insisted on keeping the meteorite alive in his stories, Hagen remembers her mother, who was five in 1930 and slept through the whole thing, hardly mentioning it. (“It skipped that generation maybe,” Hagen says.)

In fairness, Hagen admits, her mother was busy with her life—traveling to Chicago to build airplane engines during World War II, raising her family and working her farm—much as Hagen became busy with her own. Eventually, she would see a smaller chunk of the Paragould meteorite on display at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., but viewing it in person, while impressive, isn’t what makes that memory special: It was the photos she got with her son and grandson.

That’s not to say that the shadow the meteorite cast on the town ever really went away. It was always a part of them—but that’s mostly all it was: a shadow. Because as much as one wants to say that the meteorite played an outsized role in the northeastern Arkansas community’s sense of self and identity—that there were small-town festivals dedicated to it, that teachers had their kids making papier-mâché meteorites on a yearly basis—that simply wasn’t the case. Beyond the stories, the sum of the meteorite’s presence was mostly found at the Greene County Museum, preserved by a smattering of newspaper clippings, archival photos, and a needlepoint depiction of the meteorite falling entitled “A Cosmic Interpretation.”

At least, until it fell to Paragould once more.

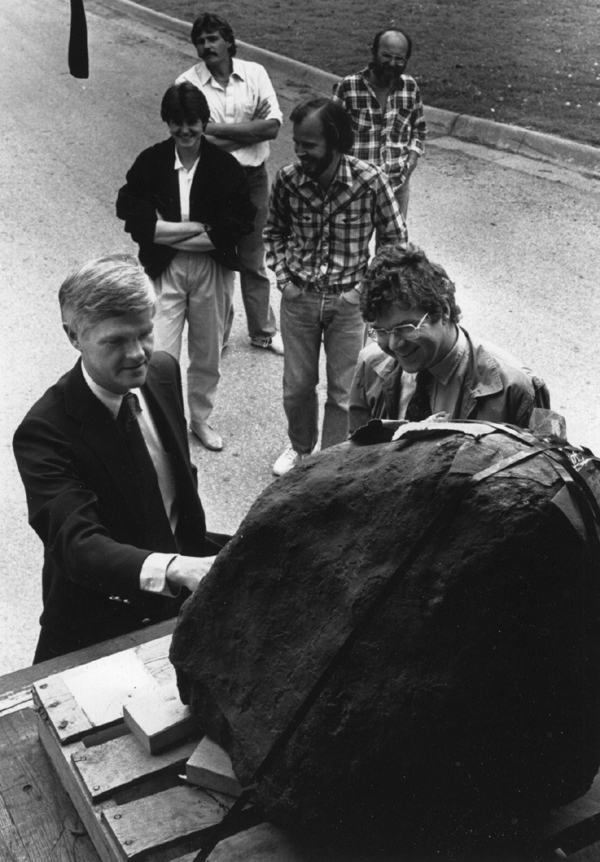

When the meteorite returned to town on May 19, 2023, it didn’t disrupt the atmosphere with fireballs and sonic booms. It came in a white-paneled van and required five strong-looking guys to roll it up the sidewalk. It was largely unchanged from when it’d left nearly a hundred years prior—save, that is, its title of “largest meteorite seen to fall,” which it lost to a stone weighing a literal ton that plummeted to Earth over Norton County, Kansas, on February 18, 1948.

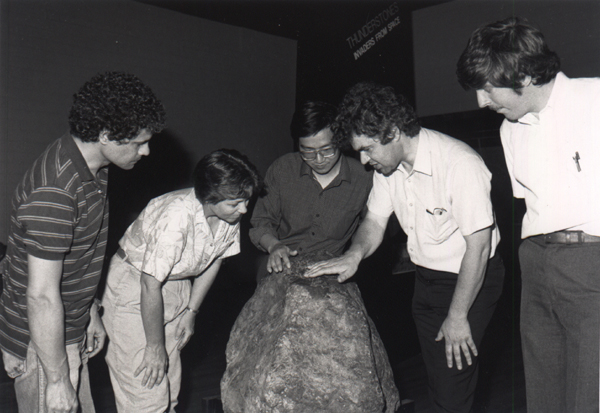

For thirty-five years, the Paragould meteorite had been housed at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, some two hundred miles to the west, nearly five hours by car. It landed there in 1988, when Derek Sears, a professor at the U of A, had written to the Field Museum asking to include the stone in an exhibition of Arkansas meteorites. In the years that followed, it made a circuit through the university, with stops at the museum, library, and Center for Space and Planetary Sciences.

Around 2008, in the early days of the Greene County Museum, there had been some hope that the meteorite might find its way home—that it’d join other pieces of Paragould history, like the county’s first television or the lanterns from once-bustling Paragould Union Station—but those hopes had been stymied by a thicket of bureaucratic red tape.

Ultimately, it took six months of emails exchanged between the Paragould Chamber of Commerce and the Field Museum, along with some $8,000 to cover transportation costs from the University of Arkansas to the Greene County Museum.

If all goes to plan, the Paragould meteorite will be on display there for the better part of a year—including during the eclipse in 2024—with the option to extend should there be a need and a want for it, which there is.

In the time since it’s been back—taking up residence just inside the door of the museum, displacing some of the personal effects of former Governor Junius Marion Futrell, who once owned the house the museum now inhabits—the rock has already started to reignite stories and long-dormant connections in the community. This is evidently the case among both the very young (like the eighteen-month-old who blurted out the word “mee-tee-oh-right” upon seeing it) and the very old (like the elderly woman who launched herself off of her walker to catch the meteorite in a bear hug before museum staff could explain that the 4.5-billion-year-old rock was not for touching).

But one thing that’s clear: All the stories, new and old, are not about the meteorite. Not entirely.

To really understand what that means, you’ve got to talk to Kenny Pegg, one of the founders of the Greene County Museum and a regular volunteer there.

If you happen to catch him and ask about his personal ties to the meteorite, he’ll say that his mother, Wanda, was born on the very day that the meteorite fell to earth. He’ll explain that she would, until the end of her days, tell people that her birth was so auspicious that the good Lord had seen fit to send a meteorite to announce it. Or how, nearly twenty years ago, after Pegg’s daughter, Kara, “discovered” the Paragould meteorite in a tucked-away part of the Mullins Library on the University of Arkansas campus, marked the first time Wanda got a chance to see the phenomenon that had heralded her birth.

Not everyone who admires the meteorite has a mother who was born under it, of course, but its meaning to those whose families were touched by it, either directly or indirectly, seems to go beyond just a fondness for the rock. Because while many of the stories they tell fall along the same lines, the tellers they describe—the people who told them the stories—are where the root of the connection lies. It’s a cosmic thing, yes, but it’s also very universal, the most human thing of all, to love this rock.