Frank Lloyd Wright is known for designing some of the most innovative structures in America, and many of them, like Taliesin and the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center in Wisconsin, are pilgrimage-worthy Midwestern destinations. But the landscapes of the South also inspired the visionary architect, in spaces like Auldbrass in South Carolina, a private Lowcountry home that opens occasionally for tours. Wright’s influence on his mentees—notably the architects Arthur Kelsey and E. Fay Jones—also led to a bevy of buildings in the region. Among Florida’s lakes and in the wooded hilltops of the Ozarks, legacy structures connected to Wright illustrate his deep sense of place. Here’s where to witness it for yourself.

Florida Southern College

Lakeland, Florida

This Central Florida school is home to the largest single-site collection of Frank Lloyd Wright architecture anywhere. After visiting the campus in 1938, he developed plans for eighteen buildings over a twenty-year period. At the heart of his vision stands the sand-yellow and red ochre Annie Pfeiffer Chapel with its striking textile block construction framed in native Florida tidewater red cypress. Its geometric shape complements the campus’s Usonian house, a pioneering open-floor style of single-family home he revisited at sites around the country. “Wright strongly believed in creating buildings that harmonized with their natural surroundings,” notes Stacy L. Walsh, an associate vice president at the college. He also created a series of covered walkways, named the Esplanade, to create a sense of flow across campus and imitate the region’s abundant orange groves.

Rosenbaum House

Florence, Alabama

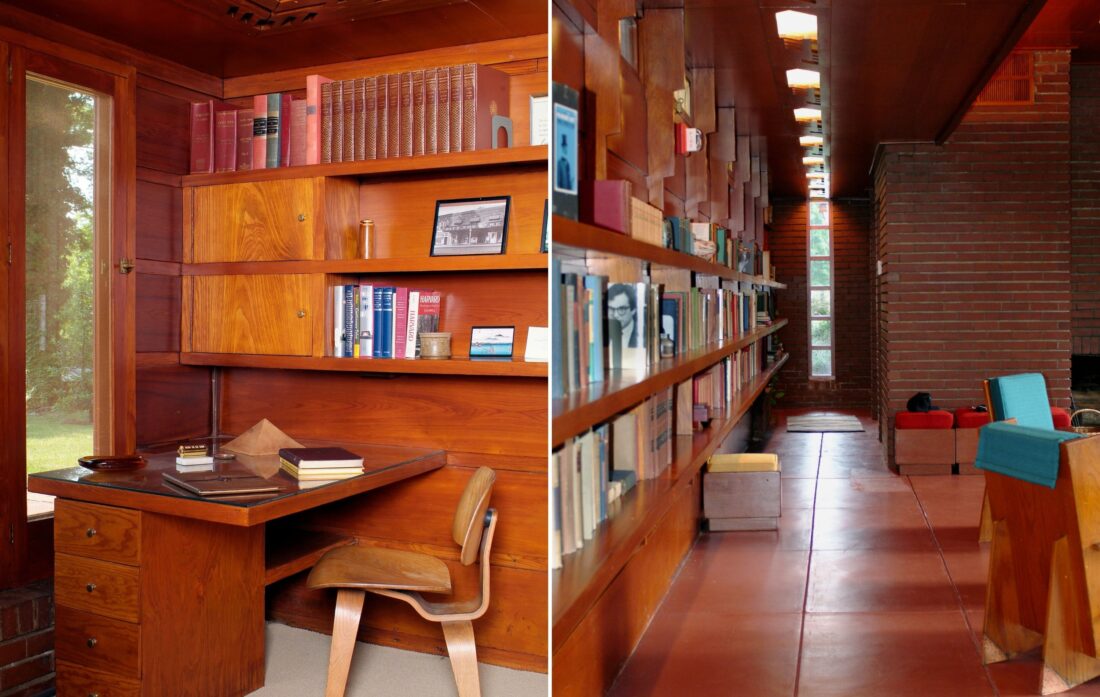

The Rosenbaum House is one of twenty-six Usonian houses built before World War II. The late Stanley and Mildred Rosenbaum, who were active in the civil rights movement, commissioned its construction, and the family lived there until 1999. Made of cypress wood and brick, the L-shaped frame includes soaring windows and cantilevered eaves. Wright even designed the custom furniture still found in the house.

After the Rosenbaums donated the house to the city of Florence, it became a museum—and an exemplary showcase of Wright’s concept of compression and release. “Spaces appear small or uncomfortable and you want to move through them—which leads to the release when you find yourself in a much larger space with an expanded vision,” says Brian Murphy, director of Florence Arts and Museums. “It’s an experience you remember.”

Skyline Lodge

Highlands, North Carolina

The Cincinnati-based architect Arthur Kelsey was an early friend and acolyte of Wright, whose influence was at its peak when Kelsey drafted the original plans for Skyline Lodge in 1936. The hotel’s Wrightian design is evident in its horizontal lines, wide bands of glass, and long rooflines in a harmonious natural setting with sweeping views of the Blue Ridge Mountains. “Guests who are familiar with Frank Lloyd Wright consistently express gratitude that we’ve preserved the original structural integrity and history of Skyline,” says Marcos Oliveira, director of lodging operations, “from the original walnut paneling in the main lodge to the granite columns to maintaining a main lobby that is small and quaint yet functional.” The centerpiece is Oak Steakhouse, a sleek, midcentury-modern setting featuring a signature south-facing stone balcony and original granite fireplaces.

Mildred B. Cooper Memorial Chapel

Bella Vista, Arkansas

After meeting Wright at a convention, E. Fay Jones became his apprentice at the famed Taliesin East for the next decade. A native of Arkansas, Jones designed this nondenominational chapel, constructed in 1988, in his home state alongside partner Maurice Jennings. Perched on a wooded hillside along Lake Norwood, it features nearly 4,500 square feet of glass, and the open-air design includes towering Gothic arches of ethereal wood and stone that nod to the surrounding Ozark landscape. Jones, who admired Wright’s organic aesthetic, used a similar design for Thorncrown Chapel just outside Eureka Springs.

The John B. Begley Chapel at Lindsey Wilson College

Columbia, Kentucky

E. Fay Jones also used his apprentice experience to design the John B. Begley Chapel, which stands at the center of Lindsey Wilson College and weaves agrarian design elements into the traditional red-brick building campus. Duane Bonifer, a longtime college employee and currently an assistant to the president of the college, worked on the project with Jones. “While Jones drove around the region,” Bonifer says, “the one architectural style he noticed was the silo, so he decided to have that be reflected in his design. And because he considered himself to be a ‘cathedral builder born five hundred years too late,’ Jones said he wanted the building to have a Neo-Gothic style—which explains the three crowns, which some people call domes, as well as the high ceilings.”

Bonifer says the chapel reminds people of their place in the world. “In true Frank Lloyd Wright style, form follows function in the sanctuary…When [visitors] enter the sanctuary, their heads are always lifted up. In fact, whenever I give a tour of the chapel, I like to be about twenty steps into the sanctuary so I can watch everyone’s heads jerk up to the skylight. Fay Jones said that was to remind people right away that there is a larger being in the universe and we are to contemplate our place and duty in it.”