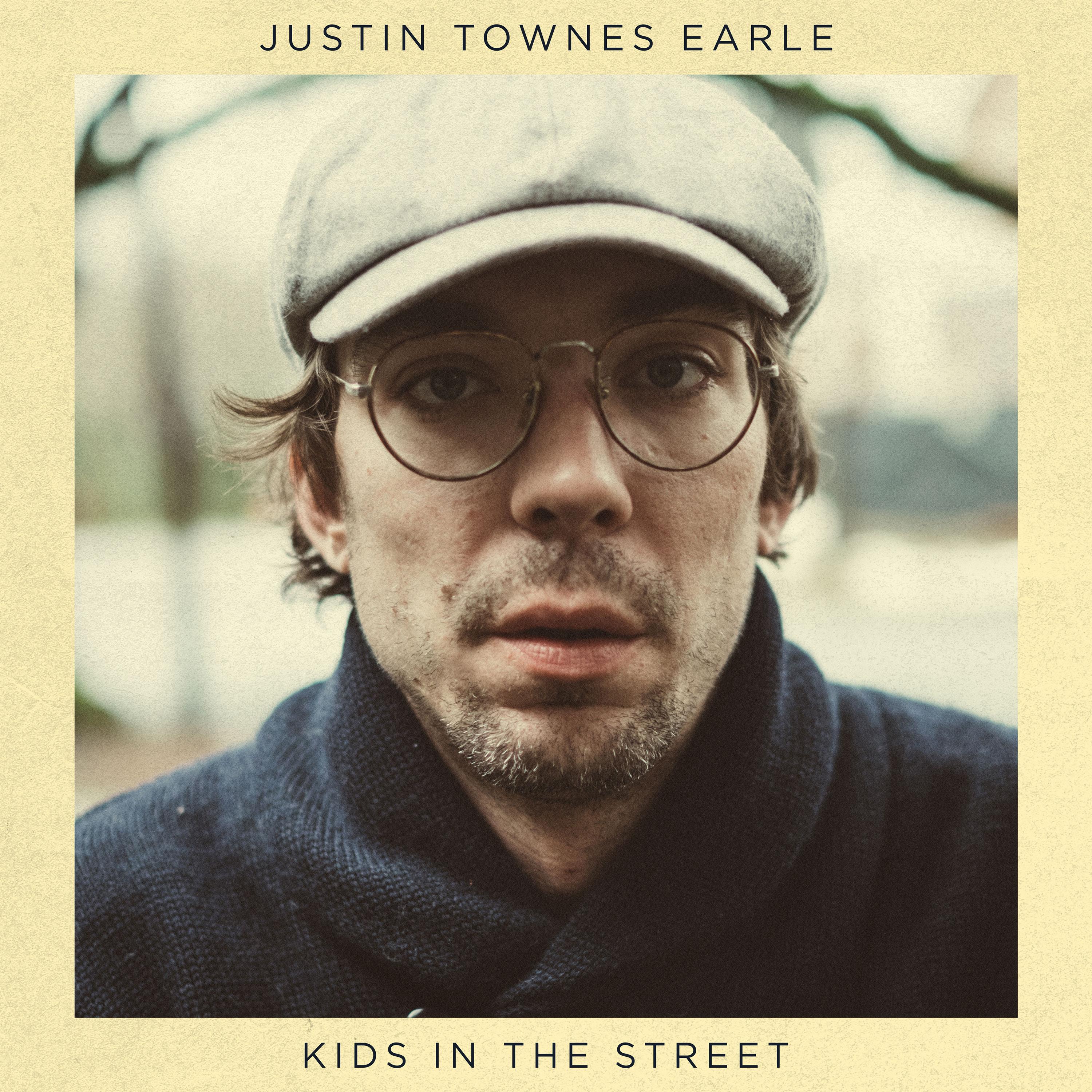

As a songwriter, Justin Townes Earle has never been one to shy away from heavy subjects, whether he’s laying bare the rocky relationship he had with his father, Americana outlaw Steve Earle, or using up-tempo melodies to temper lyrics about the despair hard living can bring. The 35-year-old singer-songwriter writes from experience: he got into playing music, touring and drugs as a teenager, dropping out of school to work on the road. Since his first album, The Good Life, debuted in 2008, he’s gotten sober, gotten married, and continued to tour and record almost constantly. Still, Kids in the Street—his eighth full-length album—represents plenty of firsts for the Nashville native.

For starters, Earle worked with an outside producer for the first time by tapping Mike Mogis, whose resumé includes work with indie icons Bright Eyes and former Rilo Kiley frontwoman Jenny Lewis. Kids in the Street breaks new ground lyrically, too, tackling gentrification in Nashville with a poetic straightforwardness. A nod his lower-middle-class upbringing, buoyant album opener “Champagne Corolla” frames its chorus around an ordinary sedan rather than the flashier vintage cars so often romanticized in song. Meanwhile, “Same Old Stagolee” re-interprets an old folk song by name-dropping Nashville spots—Murfreesboro Pike, Chestnut Hill—and setting his characters in areas that now fall into the vastly redeveloped So-Bro neighborhood. On “There Go A Fool,” which Garden & Gun is excited to exclusively premiere today, the verses touch on tales of rock-bottom, inspired by an empty Music City storefront.

Garden & Gun caught up with Earle to talk about how Nashville has changed, the process behind Kids in the Street, and the influence of personal milestones on his everyday life. Stream “There Go A Fool” and read the interview below.

You talk about Nashville on this record. Did you go into the writing process looking to shine a light on the way the city has changed?

With this record I definitely approached that subject bluntly for the first time, calling out specific places in Nashville. I’ve traveled the world since I was 15 years old, working on the road, so when it comes to the gentrification process, I’ve seen it happen in cities all over. Nashville did it at a rapid pace with a complete disrespect for the past—no regard whatsoever. There’s a part inside of me now that says I’m not from Nashville. I’m from old Nashville. And that place does not exist anymore… There is nothing that is sacred to me, except for my mother, left in that town anymore.

Are there elements of that feeling in “There Go A Fool”?

It was one of those songs that came to me in a strange kind of vision. There’s a bar in Nashville that was there for years. One day I looked in, and I noticed it was gone, but the building was still there and everything was still inside it, paused in time, looking exactly like the last time I saw it.

I remember the old men that sat in there back when I was a kid, wearing their sport coats and drinking and whatnot. It wasn’t a place where people drank for celebration—it was where horrible addiction compels you. And I don’t know why, but it was a very vivid, almost lucid dream: I saw this particular scene of a guy trying to buy a drink, it being poured, and him putting his hand on it, reaching in his pockets, and realizing he has no money—he’d been getting ahead of himself. The song was kind of built off of that.

“There Go A Fool” has fuller instrumentation behind it than some of your previous work. Were you going for that from the beginning?

I was looking more, I think, towards Aaron Neville’s “Tell It Like It Is”—going for a little bit more of that New Orleans kind of soul that existed in the 60s and 70s. Mike Mogis definitely brought more instrumentation to it. If it had been just me, I would have just had real simple, sparse guitar and bass, you know? [Laughs]

Watch: G&G’s Back Porch Session with Justin Townes Earle

You have a lot of other changes going on in your life—this is the first record you have written since getting married. What effect has that had on you?

As a person—as a human, as a man—my wife just fills all the gaps, fills up all the holes that I have in my life. It’s one of those things that’s very hard to explain. I’m a much more patient man these days—which isn’t to say that I’m patient. [Laughs] I’m just more patient. I have to think seriously about, for the first time in my life, how what I do is going to directly affect somebody, every move I make. It’s gotta make you better. Well, it will either make you better or worse. You won’t be married long, I guess, if it makes you worse.

You’re writing a lot about the neighborhoods and places you remember from childhood on this album. You’ve also featured kids on an album cover before, with Single Mothers in 2014. Now, “kids” is right there in the album title. Is there something about those younger years that interests you?

Especially now, with a daughter coming, I’m interested, you know: what do kids do? ’Cause I don’t really know that. I was, unfortunately, put in some terrible situations very early in my life, and I grew up very fast. I don’t know what it’s like to be a 12- and 13-year-old. Because at 12, I was a few years away from moving out of the house and being gone and playing music for a living. So yeah, I’m curious about how it actually works. Or how it’s supposed to work.

Kids in the Street is set for release on May 26 via New West Records, and is available for preorder from PledgeMusic.