Arts & Culture

The Saga of the Tybee Bomb

In the late 1950s, a U.S. Air Force B-47 on a training mission jettisoned a hydrogen bomb somewhere in the ocean near Savannah. Sixty years later, steeped in local lore and Cold War intrigue, Tybee’s “broken arrow” remains one of the great Southern mysteries

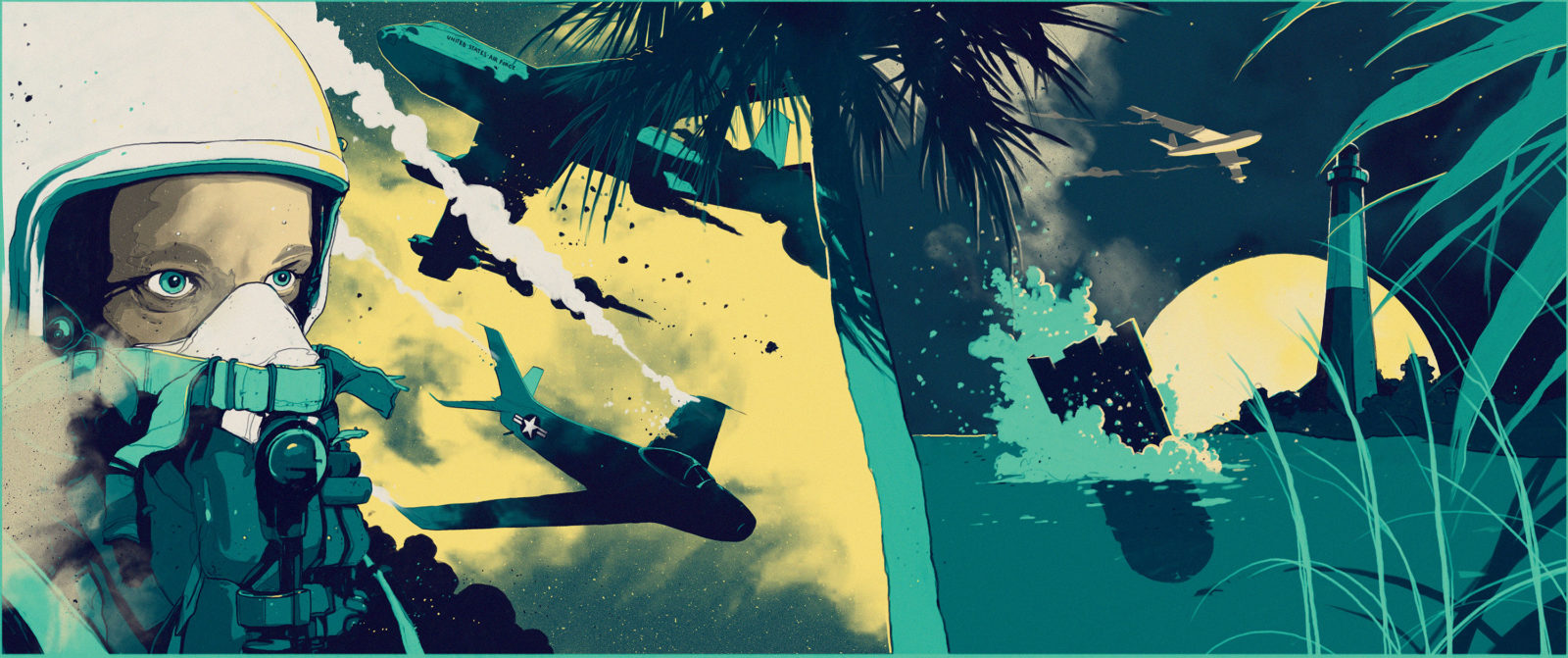

Photo: Simon Prades

H-Bomb Mark 15: Irretrtrievably Lost.

The skies above my home on Daufuskie Island, South Carolina, February 5, 1958, around 1:00 a.m.: At thirty-eight thousand feet, on the very edge of space, an air force B-47 Stratojet was in trouble.

I was twelve years old.

The bomber, under the command of Major Howard Richardson, was on the way back to Homestead Air Force Base, Florida, after a simulated bombing of Radford, Virginia.

It was carrying a roughly four-megaton hydrogen bomb. In combat, Richardson might have been flying out of Alaska to incinerate Vladivostok, but until then, Radford would suffice.

Major Richardson thought the exercise was over, when an F-86 Sabre jet out of Charleston collided with his aircraft during a simulated attack. The F-86 spun out of control, but the pilot, Lieutenant Clarence Stewart, ejected and survived, though severely frostbitten from the high-altitude cold. Stewart landed in the Savannah River swamp, on the South Carolina side. There were no gators awake in February to eat him as gators have done to victims of aircraft crashes before. But as he recounted in the Washington Post in 2005, he had landed “in a little clearing in the biggest damn swamp in South Carolina.” He deployed his life raft and crawled inside, making a hasty shelter. Eventually he heard the sound of an approaching aircraft. Stewart struggled with his flare pistol, but his frostbitten fingers would not work. He nearly shot his own toes off, and the flare exploded at his feet. But the noise of the gun set a hound to barking, and a ranger tracked Stewart down, figuring him a poacher.

The rescuer doctored his charge with some moonshine, and Stewart attempted to call Charleston Air Force Base collect, but the charges were refused. The ranger then drove Stewart to a nearby hospital, where he was picked up by an air force helicopter and returned to Charleston. In the hospital, the air force decided to amputate most, if not all, of Stewart’s fingers. When he threatened to flee, they relented. Stewart eventually returned to duty and later flew combat missions in Vietnam, where he earned a Silver Star. Oddly enough, Stewart’s F-86 landed relatively intact—minus wings and pilot—in a field outside Sylvania, Georgia.

While Lieutenant Stewart was parachuting toward the swamp, Major Richardson was trying to regain control of his damaged B-47. He radioed Hunter Air Force Base in Savannah for an emergency landing, but the single runway at Hunter was under repair and too dangerous to use. The bomb on board was more than ten feet long and weighed seven thousand pounds. If the bomber was brought up short on the uneven runway, its payload would most likely tear loose and exit the aircraft, “like a bullet through a gun barrel,” Richardson later said, killing anyone in its path. Nobody wanted to speculate if the bomb would detonate under such impact.

Plan B: Richardson would jettison the bomb into the ocean instead. Survival of the crew was an official top priority. The crew noted no explosion when the bomb struck the sea, just off Tybee Island, eight miles south of Daufuskie. They wrestled the B-47 to safety at Hunter. For saving his aircraft and crew, Major Richardson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Simon Prades

Air force records indicate the Mark 15 bomb bore serial number 47782. It contained four hundred pounds of high explosives and an undisclosed amount of enriched uranium and other nuclear material. When armed with its nuclear capsule—a device containing plutonium, which triggers the nuclear explosion—the bomb was capable of producing a fireball with a radius of 1.2 miles and causing severe structural damage and third-degree burns for ten times that distance.

A recovery effort began on February 6, 1958, for what became known as the Tybee bomb. On April 16, 1958, the military announced that the search efforts had proved unsuccessful, although the team had discovered several Civil War cannonballs, still full of explosives.

Broken Arrow: military jargon for a lost nuke.

Several weeks later, the Savannah Coast Guard allegedly received reports of a Soviet submarine just off the coast. The Soviets had already successfully tested their own hydrogen bomb in 1953, but an intact American weapon would have constituted an intelligence coup. Presumably, the Russians did not find the bomb either. Or if they did, they kept mum.

Simon Prades

Völkenrode, Germany, May 1945: The shooting had barely stopped when Boeing sent its engineer George S. Schairer to help assess results of Nazi experiments in combat aircraft design. The Germans had previously attacked London with drone “buzz bombs” and the V-2 rocket, the first successful ballistic missile. They had experimented with futuristic “flying wing” aircraft and had the first operational jet fighter, the fearsome twin-engine Me 262. No other fighter could touch the 262, and it eventually downed hundreds of Allied planes. But like many German technological advances, it came too late to affect the outcome of the war.

At Boeing, Schairer had helped design the B-17 Flying Fortress and the B-29 Superfortress, which dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Pawing through the trove of captured documents, he found things of considerable interest, including results from wind-tunnel tests on the Me 262’s swept-wing design. Schairer sent a letter to Boeing with information on what he’d found, and when the air force went looking for a new nuclear-capable bomber, Boeing was ready.

The resulting B-47 was revolutionary. It had wings swept back at thirty-five degrees, and jet engines hung below the wings in pods to improve aerodynamics and shed heat faster. Eighteen small rocket boosters helped with takeoffs, and a parachute slowed it down for landings. In 1949, the new bomber crossed the United States in under four hours at an average 608 m.p.h. It was so fast no Russian fighter could catch it. While earlier bombers bristled with guns, the B-47 only had remote-controlled weapons in the tail, as engineers believed an enemy interceptor would only get a parting shot. There were no operational SAMs, surface-to-air missiles, in those days.

Based at airfields across the United States and deployed to England, Greenland, Morocco, and Spain, the B-47 became the foundation of the Strategic Air Command. But while the aircraft may have been fast, sleek, and beautiful, it was so radical in design and function that Holden Withington, Schairer’s engineering partner, had doubts whether it would fly at all when he watched the prototype taxi for takeoff. Early jet engines were dangerously slow to accelerate. The thin wings flexed as much as seventeen feet in flight; controls were sluggish near top speed. The slightest inattention, while responding to a radio call or a system failure warning light, could have deadly consequences. In 1958 alone, the year Major Richardson’s plane jettisoned the Tybee bomb, there were thirty-three B-47 accidents and fifty-eight fatalities. Between its initial acceptance by the air force in 1951 and its official retirement in 1965, 10 percent of the fleet was lost, a failure record that the military would deem entirely unacceptable today. The damaged aircraft Richardson managed to safely land at Hunter in February 1958 never flew again.

All the roads down here are dead ends, or at least most of them are. The Lowcountry coast is intersected by broad, deep estuaries, and there is no stunning coastal highway like California’s cliff-hugging 101. I-95, our main north-south corridor, is sometimes forty miles from the sea, and U.S. 17, the famed Ocean Highway, rarely crosses salt water. Edisto Beach, just south of Charleston, for example, is clearly visible across the water from Harbor Island on the south side of St. Helena Sound, but it takes two hours to get there by car.

As a result, isolated coastal communities seek their own identity: Sullivan’s Island, east of downtown Charleston, where Edgar Allen Poe languished while in the army, celebrates its connection to “The Gold Bug.” Farther south, Folly Beach is “the Edge of America,” with an abundance of associated weirdness. In Georgia, Cumberland Island has its wild ponies and Carnegie ruins, Jekyll is the former playground of the robber barons, and tiny Tybee, population 3,100, eighteen miles from Savannah down dead-end U.S. 80, hosts the Beach Bum Parade every May with the South’s largest water fight. Rules are simple: no bleach water, no ice water, no pressure washers, no water balloons or buckets, don’t squirt the cops. Floats range from the zany to the profane. In 1998, a Save Our Tybee Bomb float joined the lineup, featuring scantily clad damsels straddling a mock-up Mark 15 device like Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove.

Public interest in the lost Tybee bomb had been eclipsed shortly after the incident by an accidental bombing of some chickens behind a home in Mars Bluff, South Carolina, by another B-47 on March 11, 1958, when the bombardier-navigator unintentionally grabbed the weapon’s emergency release. The nuclear capsule was aboard but not inserted into the bomb, a smaller Mark 6 device. Still, conventional explosives detonated, injuring six, killing chickens, caving in the house’s roof, and blowing a thirty-foot hole in the ground.

In the decades that followed, the Tybee bomb lay pretty much forgotten. But forty years later, along came Lieutenant Colonel Derek Duke, USAF (retired), who had the odd habit of chasing lost nukes. Duke, then an instructor for commercial airline pilots, was at an air force reunion in Charleston in 1998, hoping to meet the navigator of the B-47 that nuked the chickens. But when the navigator failed to show, Duke went online to learn more. That’s when he discovered the Tybee bomb.

Duke did more research, eventually coming upon a letter written to a congressional committee in 1966 by W. J. Howard, then assistant secretary of defense. Howard had been asked to furnish a list of accidents that had resulted in lost nuclear weapons, and in the letter, he identified two involving “complete weapons.” One was an incident in 1965 in the western Pacific, in which a plane had gone over the side of an aircraft carrier in 2,700 fathoms. The aircraft, pilot, and weapon were never recovered. The other was the Tybee bomb.

Alarmed, Duke contacted a local congressman, Jack Kingston, who demanded an explanation from the air force. The official reply: The bomb contained no capsule and presented no public safety hazard. Duke persisted: Even if the bomb wasn’t fully armed, it contained four hundred pounds of conventional explosives and weapons-grade material that could fall into the wrong hands or release a plume of radioactivity. The air force concluded that due to the potential environmental impacts of a search and the safety issues involved with the conventional explosives, the Mark 15 was better left undisturbed. After further questioning, Howard said he had been mistaken and the bomb was not complete. Case closed.

Duke took partners, raised money. No, he would not try to recover it, but using magnetometers and Geiger counters, he wanted to find it, then shame the air force into picking up after itself. Duke certainly tried, and at one point believed he had found elevated radiation readings near the bomb’s presumed location in Wassaw Sound, which prompted the air force to send its own team to investigate. But their survey found no evidence of levels in the area beyond what could be considered naturally occurring.

All the publicity surrounding Duke’s search raised the ire of Richardson, then a retired colonel living in Mississippi. In 2008, Richardson wrote an opinion piece for the Savannah Morning News, calling any allegations the bomb could cause a nuclear explosion a “disgraceful fraud” perpetrated to gain publicity and make money. Richardson noted the receipt he had signed when he took custody of the bomb, wherein he promised, “During this maneuver I will allow no assembly or disassembly of this item while in my custody, nor will I allow any active capsule to be inserted into it at any time.” Indeed, Richardson wrote, his aircraft had no capsule aboard.

For his part, Duke wasn’t buying the military’s story. In a book he published about his research, Chasing Loose Nukes, he maintained the Mark 15 bombs were so big, there was no room to arm them from within the aircraft. Instead, the capsule was always loaded into the bomb’s tail while still on the ground, and the pilot could then mechanically move it into firing position just before a bomb run. Furthermore, he quoted one Howard H. Dixon, whom he identified as a former crew chief who loaded nuclear weapons onto planes at Hunter from 1957 to 1959: “Never in my Air Force career,” Duke said Dixon told him, “did I install a Mark 15 weapon without installing the plutonium capsule.”

Danger or dud, who knows? Whatever it was, on Daufuskie we were sitting pretty much right on top of it.

Photo: Courtesy of the Douglas Kennedy Collection.

Aircrew of B-47. From left: Major Howard Richardson, 1st Lieutenant Bob Lagerstrom and Captain Leland Woolard. (U.S. Air Force).

Savannah River channel, November 11, 2006: Bubba Smith, a good man, was dead at the helm of the trawler Agnes Marie. He was seventy-four.

Big truth down here: The sea always gets its due. Three shrimpers lost just last year, no bodies recovered. Others slowly die of melanoma, gone to the guts and bones of men too long in the sun. Just before he died, friends trundled Bubba aboard Agnes Marie and propped him up for his last trawl, and Bubba went out the way he wanted, his hands on the wheel.

The old single-haul boats are gone now, and most trawlers pull two nets, sometimes four, long mesh socks, doors to keep them open, floats to keep them up, weights to keep them down, and turtle excluders to capture and automatically release the endangered loggerheads they might inadvertently snag.

But shrimp nets are not fitted with bomb excluders.

Bubba had a grandchild on Daufuskie. She grew up tall and lean, lovely and mean, breaking hearts, horses, dirt bikes, and bones. He didn’t want to see her die in a nuclear explosion. So, the last time he was in the hospital, Bubba called a friend and fellow shrimper to his bedside. “I’m fixing to die, but I want to tell you a story first. Nobody gives a rip but me.”

Bubba told this story: About 1960, as best as he could recall, he snagged something heavy in front of the Tybee public fishing pier. First, he reckoned it an engine block from a wrecked trawler. He dragged it several miles south along the beach, around the point into the Back River. He tried to raise it, but the winch smoked and the outrigger buckled. He hired a diver. Bubba just wanted his net back.

The diver came up wild-eyed, spit out his mouthpiece. “It’s a bomb!”

“We left the sum-bitch right there,” Bubba said, “just off the dock at the old coast guard station.”

John-Boy Solomon is a shrimper too, a scrapper, been in jail a time or three, a man not afraid to throw a punch or speak his mind. The man who heard Bubba’s almost-deathbed confession was his uncle, and the story became a staple in Solomon family lore. One day, John-Boy took to fretting over the air force’s disinterest, got into his whiskey, called Hunter airfield, and was directed to a public-affairs officer who was not even born when Richardson jettisoned the bomb. “I know about where that damn bomb is! When you bastids gonna do something about it?”

“Where are you calling from, sir?”

“Tybee Island.”

“Well, sir, if you have concerns about a bomb, I suggest you hang up and call the Tybee Island Police Department.”

I told Bubba’s story to Derek Duke.

“I heard that story too, but I don’t believe it,” Duke said. “I think the bomb is somewhere out in the marsh behind Ossabaw Island.”

South of Tybee, Ossabaw is a nine-thousand-acre state nature preserve where you don’t set foot without permission.

“How in the world did it get there?”

“Tide and waves,” Duke said.

“That bomb is heavier than a Toyota. And it was washed up into the marsh by the waves and tide?”

“Yep,” he said.

But the retired lieutenant colonel never worked a shrimp net.

Daufuskie Island, July 10, 2017: I had John-Boy Solomon on his cell. He was ten miles offshore, and the signal was breaking up in the isobars. John-Boy was distracted, five hundred pounds of fat white roe shrimp twitching and jumping on the aft deck—expenses and two weeks’ wages, with little sharks, stingrays, and jellyfish among them.

“You gonna tell me more about Bubba and the bomb?”

“What else you wanna know?”

“Everything.”

Long pause. “I’m kinda busy right now. Can I call you back?”

“Just swing by next time you’re on the island. I’ll buy you a drink.”

He promised he would. I’m still waiting.

Another big truth down here: The sea does not easily give up its secrets. Even a seven-thousand-pound bomb.