She’ll tell you with a wink to refer to her as Lee Smith, OaD. (The “OaD” stands for “old as dirt.”) But it was as a little girl that Smith first began scribbling stories in the coal-mining town of Grundy, Virginia, and by her twenties she had already gained a reputation for writing about Appalachian lives in rich detail. With thirteen novels, four story collections, and a memoir, Dimestore, Smith has become an essential voice in the Southern literary canon, winning accolades that include the Robert Penn Warren Award for Fiction and the Southern Book Critics Circle Award. She still writes every day, although now she does it from an antebellum outbuilding ten feet from the house she shares with her husband in Hillsborough, North Carolina. “There’s nothing equal to that feeling when you’re writing and it’s really working,” she says.

Writing is an art, but publishing is commerce. How do you reconcile them?

I may have less trouble with that than some writers, simply because I’m a merchant’s daughter. I grew up working in my father’s dime store. The truth is, I like to sell books. I like to work a room. Writing is very lonely. There you are, shut away for hours, days, months, years. When it’s time to go around to bookstores and give readings, I’m ready.

How often does it hit you just how many people have read your books?

It doesn’t, really. I live in a little town where if you throw a rock, you hit a writer, so it’s not a big deal. Hillsborough has always been kind of a leafy, dreamy town that’s a haven for writers and artists and outlaws.

What about when you travel?

Sometimes I sit down on a plane next to somebody who’s reading one of my books. The first thing I ask is if they like it. If they do, then I say who I am.

And if they don’t?

Then I don’t say a thing!

Do you want to express different things in your writing now than you did earlier in your career?

Totally. I write fiction the way other people write in their journals. Fiction has always been how I try to make sense of my own life. I am not my characters, but often they are going through things I’ve been through. I can read over an old story and remember exactly who I was then, where I was, and what I was dealing with when I wrote it.

How does that feel?

It brings everything back. When we first start writing, we’re writing the great dramas of our childhoods, our young adulthoods. We’re going for intensity. At my age now, I’m more interested in the long haul than the epiphany.

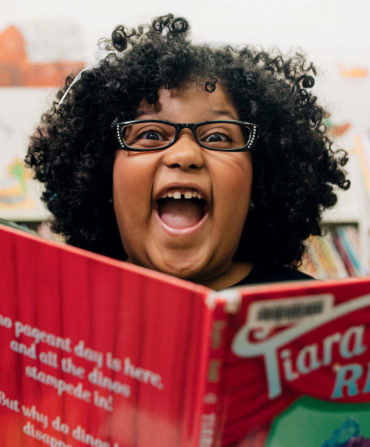

Photo: Geoff Wood

Lee Smith at home in Hillsborough, North Carolina.

Storytelling is personal, but it plays a larger role in society.

Oh, storytelling is crucial to the future of our country. We cannot cover up history. We have to find out who we were, where we came from, how we lived, and what we believed, before we can understand what’s happening now. I’m delighted to see the recent emphasis on oral history in schools and on the radio and in documentary films. I think it’s sort of the art form of our time.

What do you think about the glamorization of the culture you grew up with? Does it ever make you mad to see a ten-dollar biscuit on a menu?

Frankly, I’m just glad to see biscuits, wherever they may be. The ten-dollar biscuits are everywhere. So is pimento cheese. Pies, deviled eggs, shrimp and grits…and bourbon! I’ve never seen so much bourbon, and it costs a fortune. I think about it like this: Instead of being looked down upon, these parts of our culture are being celebrated. We’ve got plenty of culture in the South, so we might as well share.

What’s the thing you love to do that is the least like writing?

Most things I love to do are like writing, in a way. I love to cook, but that’s putting things together to make a new thing. It’s creating. I love to garden, but that’s generative, too. I love to dance, and that’s about finding a rhythm that’s pleasing to you. Maybe everything’s a little like writing.

What would ten-year-old Lee think of your life now?

She’d be amazed! When I was ten, we’d run up in the mountains all day long, swinging on grapevines and running wild until we heard the big bell calling us down for supper. Ten-year-old Lee wouldn’t believe all the activities for kids we have today.

I bet she’d be proud of grown-up Lee.

I don’t know. I write a lot for girls and women, particularly girls and women from the mountains, from the South, ones who don’t have enough power in their own lives—whether because they’re children or they’re poor. I hope ten-year-old Lee would be proud, but who knows? She might just want to be on her cell phone.

What advice would you give young Lee if you could go back?

“Slow down.” As a young woman, I was drunk on literature and on fire with novels and poetry and writing. I’d write all night long. Now I would say, “Slow down, honey. Read. Just because you like to write doesn’t mean you’ve got something to say. Learn about history and psychology and science and everything else in this big world. Don’t fall in love all the time. Don’t get married so fast. Life is going to be long.”

Would you have listened?

I wouldn’t have listened at all.

Read more from our August/September 2018 Southern Women collection