In the shade of a giant pecan tree on a lot that used to house an auto transmission shop on the near south side of San Antonio, Carlos Cortés continues a tradition that has been in his family for almost a hundred years. One of the country’s only masters of the art of faux bois—concrete made to resemble wood, ranging from furniture to larger structures—Cortés learned his trade from his father, Máximo Cortés, who had learned it from one of history’s greatest faux bois artists, a Mexican national and distant relation named Dionicio Rodriguez. All around the weedy patch of land stand hundreds of faux bois creations by all three men—benches, birdbaths, tables and chairs, and pieces of yard art, all twisted into organic shapes and scratched with uncannily realistic wood grain and knots.

Although the art form is most commonly known by its

French name—faux bois started in Europe in the mid-1800s and migrated to Argentina, then made its way up through Mexico and eventually to Texas—Cortés prefers the Spanish term trabajo rustico, meaning “rustic work.” “It’s a little bit heavier,” he explains, “a little less perfect. There’s going to be peeled-away bark.” It’s more folk art than fancy.

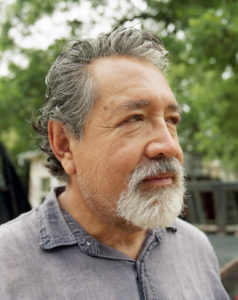

Photo: Reg Campbell

Cortés at his studio in San Antonio.

Cortés quickly developed his own variations on trabajo rustico and started making furniture. When he helped restore a famous bridge Rodriguez had built in San Antonio and that his father had also worked on, he finally felt worthy of carrying on the tradition. These days, whether it’s 105 degrees and steamy or 40 and drizzling, you can find Cortés under his tree, or inside a corrugated metal shed, pulling small trowels and handmade metal combs out of a concrete-crusted toolbox, scraping wood grain, freehand, into concrete before it dries. He begins his pieces, such as a multibranched garden bench he’s working on today, by hammering lengths of rebar into odd angles, then fitting them together into a kind of skeleton, or armature. He wraps the structure with a metal mesh that he hand ties with small bits of wire. Then come two layers of concrete and a layer of pure cement, the last a sort of creamy topcoat onto which he draws his patterns.Cortés’s process, likewise, is anything but flashy. Rodriguez died before Cortés was born, but Cortés grew up watching his father wield his craft in their San Antonio home’s little garage workshop. He’d help his dad carefully move pieces around, or sketch out a new design. Thinking he wanted to be a doctor, he went off to college to pursue that dream, only to find himself uninspired. By the time Cortés reached his mid-twenties, Máximo was almost eighty and needed assistance. “You know what you’re doing,” he told his son, and began letting him complete projects himself and keep the payments.

Photo: Reg Campbell

Detail on a finished bench.

At age sixty, Cortés is arguably busier than he’s ever been, working long hours every day but Sunday. There are a few reasons for the hectic schedule—the first of which goes by the name of Martha Stewart, who discovered a piece of Cortés’s work being sold by a collector at an art fair in New York a dozen or so years ago. Within two weeks, she was standing with Cortés in San Antonio, commissioning a few pieces, including a giant dining table for her vacation home in Maine. In talking them up, she has made faux bois (her term of choice) newly popular. “I give her all the credit,” Cortés says.

Since then, Cortés has added more high-profile patrons—there was the time Tommy Lee Jones came calling, and the project he did for the Haas family, heirs to Levi Strauss, in San Francisco—along with the locals who have long made up more than half of his clientele. But the increased attention and cash flow also resulted in slack bookkeeping. In early 2016, Cortés was indicted for failure to file his 2009 taxes and spent a year serving time. With no one to keep his partially finished projects going during his sentence, he’s had a lot of makeup work to do in addition to new commissions. “I have to get myself out of that hole that I created for myself,” he says. “I’m totally responsible. It is my fault.”

Photo: Reg Campbell

Cortés’s storage shed;

Cortés’s mistakes still eat at him, but they have also made him more conscious of his legacy. Barbara Dean Hendricks, a San Antonio author and photographer who studied Cortés’s work for her book, The Building Arts of South Texas, uses the same terms to describe his work as she does the city of San Antonio itself: “It’s natural and human scale, and yet it has a sense of permanence,” she says. “There’s something magical about it, like he stopped the decay.”

Asked to name the pieces for which he would most like to be remembered, Cortés struggles to answer. There’s a large shelter over a bus stop a block from his studio that he’s fond of. There’s the Rodriguez bridge restoration. There’s an elaborate grotto he built along the banks of the river closer to downtown. But, he says, “I’m very critical of my work. When I go back and I look at it, I see all the things that I could have done better. I guess if I’m going to be proud of something,” he offers, “it’s of continuing the tradition, not a piece—of not letting it go.”

Photo: Reg Campbell

Cortés filling in the armature of a piece.

Cortés has no apprentice, and his three children have all moved in their own directions. But there is an heir apparent, he says. His youngest cousin, Jacob Tobar, who used to work with Cortés, has taken up trabajo rustico in Taos, New Mexico. Not that Cortés is going anywhere. Máximo worked into his nineties, after all. “I don’t think I would ever want to retire,” Cortés says. “I’ll keep working the rest of my life.”