“A fellow up the road measured over 20 inches of rain,” Don Lee said as he slapped away the mosquitoes spiraling up from a muddy field underfoot. “Look around and you can tell where the wind came from. And my word, it just seemed like it wasn’t ever going to stop.” I followed his gaze across a 40-acre field of narrow-leaved sunflower, a Southern native, that looked as if it had been steam-rolled. The wind came from the north, and it stomped over every single deluge-battered plant. Normally this field is shoulder tall and so brilliantly blossomed you can hardly look at it in bright sunlight. No longer. By the time the rain and the wind did let up, much of Lee’s Garrett Wildflower Seed Farm in Johnston County, North Carolina, had been leveled.

The story of Lee’s family farm and his quest to bring back the native grasses and forgotten wildflowers of the South struck a chord with Garden & Gun readers last spring. When I called this past week to see how his family and farm held up during Hurricane Florence, Lee couldn’t hide his anguish: At least one-third of Garrett Wildflower Seed Farm’s 1,500 acres of native seed crops had fallen to the storm’s mind-boggling rains and winds. His soaring fields of Indiangrass and little bluestem were flat as wet hair. Seed heads of wild native quail foods such as partridge pea were mashed into knee-deep muck. Entire fields of pollinator powerhouse crops such as coreopsis, spotted beebalm, and other butterfly-friendly plants were lost.

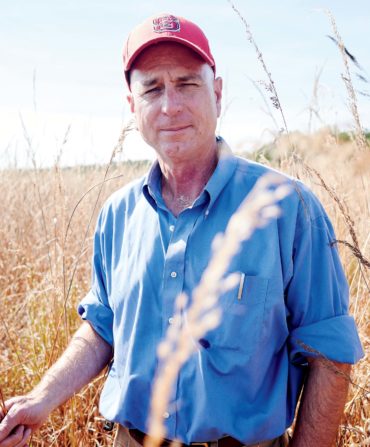

Photo: Garret Wildflower Seed Farm

A view of the same field in October 2017.

October and November are the most important harvesting months for these natives, so there’s no time to replant. And the news is even worse: A specialty farmer like Lee doesn’t raise food crops or cotton or tobacco, products that are supported with crop insurance and other subsidy programs that serve as a safety net after storms such as Hurricane Florence. So, all losses are personal losses, and will ripple through his employees, the family, and the farm.

And it’s more than just this year’s crop that has him concerned. “A lot of our crops start with seeds hand-collected from the wild,” Lee explained. “You don’t go to the seed store to start something like a restored quail prairie. It takes four to five years just to go from collecting seeds to developing a crop.” He pushed his hat back on his head, and turned away for a moment. “But I guess that’s another reality of what we do. Another peril.”

A week after the hurricane, Lee is putting all his resources into salvaging what crop is left. One bright spot in the dark storm is that his inventory barns remained intact. Which means that Garrett Wildflower Seed Farm has plenty of processed seed in inventory, ready to ship. If you’re in the market for a native wildflower meadow, or want to restore quail habitat with soaring Southern prairie grasses, or put in a pollinator mix to support bees and butterflies, go to garrettseed.com and browse his photos, and imagine your farm or backyard looking so swell, and doing wildlife a favor. He’ll ship in quantities from one pound to a truck load. Your order would never be more welcome—or more needed—than now.