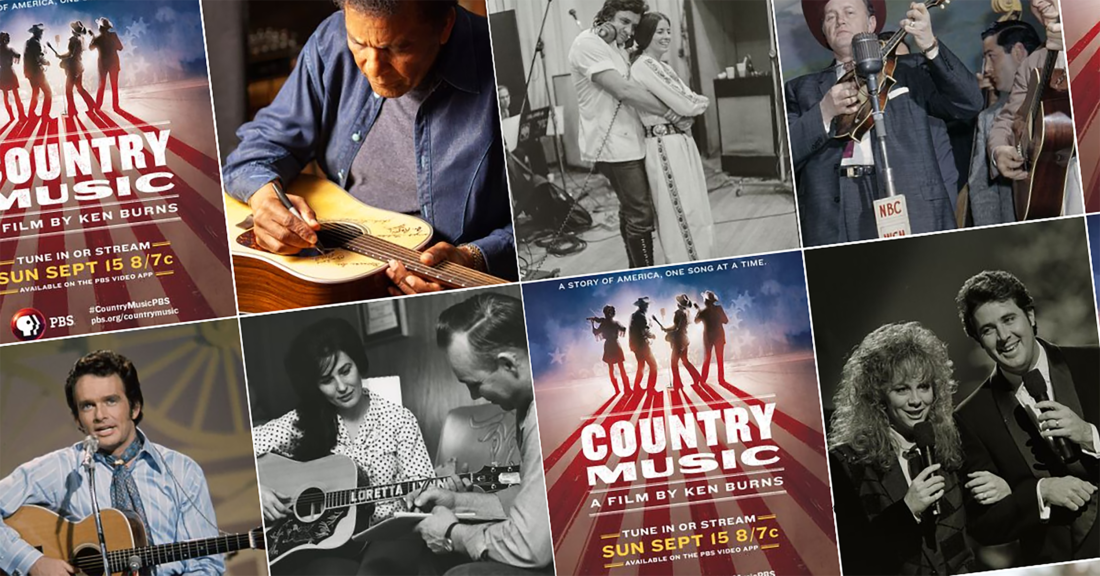

When Ken Burns decides to cover a topic, set aside some time to dig in. Best known for his epics, including his Civil War documentary, which aired on PBS over five nights in 1990 to an audience of 40 million people, the filmmaker is now readying for the premiere his latest deep-dive, Country Music. The eight-part, sixteen-hour film takes a magnifying glass to the forces that shaped this distinctly American sound. “I’m looking for stories, and I’m looking for stories that are firing on all cylinders,” Burns tells Garden & Gun. “And please tell me about the American subject that would be firing on more cylinders than the history of country music, because I don’t think you can.”

Ken Burns.

The film runs chronologically, tracing the many influences that shaped country music, from enslaved people bringing the banjo across the Atlantic from Africa all the way to the heyday of pop-country in the mid-1990s. The genre, Burns reveals, is less a set of rules and boundaries than it is a spectrum—one that trades on universal truths and bridges cultural, racial, and economic divides.

We caught up with Burns to talk about the making of the film, the contemporary artists preserving the genre’s history, and what he discovered about country music—and America—along the way. Read the interview below, and catch Country Music’s premiere this Sunday, September 15, at 8 p.m. Eastern on PBS.

Where there any misconceptions about country music that you went in expecting to debunk?

Country music isn’t just one thing. It’s never been just one thing. Even the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, the two acts recorded at the big bang of country music in 1927, don’t sound anything alike. And within themselves, they represent lots of diverse interests—African-American influences, Scotch-Irish influences, all these different kinds of ingredients go in. And that’s true of everything in America. So I assumed we would be exploding the presumption that country music is this white, Southern, rural, conservative music. And it is that, but it is also so many, many other things, and we rejoice in being able to share those many, many other things along with the white, Southern, rural, and conservative part of it. We’re not trying to make political films. That’s so binary and so limiting. We’re interested in telling complete American stories.

In the film, you note that controversy surrounding what is or isn’t country music actually sparked one of its most vibrant eras—the 1970s. Was the struggle over defining the genre always a part of its evolution?

I think it’s a natural inclination of the art form not to seek its own level, like water, but to push and strain beyond its borders. In country music, that engenders not only great periods of creativity, but also a worry and insistence that we not forget the traditions. There’s a wonderful balance between the impulse to remain the same and the impulse to be different and try something new. It may be generated by creativity, and it may be generated by commerce. When rock ’n’ roll was ascendant in the ’50s, country music was just dying on the vine, and the Nashville sound, smoothing out country’s rougher edges in an attempt to cross over, was a reaction to that. There were a lot of purists saying, “Hey, that isn’t right.” But I would submit Patsy Cline’s version of Willie Nelson’s great classic “Crazy” as an example that the Nashville sound works—and it’s still country music.

We see that tension several times in the film: The labels and the gatekeepers pushing artists to do what they think the public wants and often the artists themselves wanting something different.

It’s been there since the very beginning, when Ralph Peer was recording Fiddlin’ John Carson. You have the impetus and the momentum of commerce, and then you have the requirements of creativity…and they’re not always in sync. These are lawful kinds of tensions, natural kinds of tensions that take place. No one is necessarily wrong. If you want to sell records and get [the music] out to the most number of people, then you’re reaching the most number of people, which is what the artist wants, too. At the same time, there’s something stultifying about merely being a cog in an industrial concern, and so you have guys like Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark and Rodney Crowell saying, “Look, I think I want to choose to be an artist, and I’m not going to have this big success, but I’ll be true to myself.” What’s so great about the story of country music is that so many of the artists have it both ways. They get to be themselves and also have that enormous success.

You’ve said that you were intentionally unfamiliar with country music when you started this film. Why was that important for you, and what surprised you?

Everything about this surprised me. I’m a child of R&B and rock ’n’ roll, and I worked in a record store in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the late ’60s. So I sold country music. I’d heard it. Johnny Cash crossed over, and we loved Johnny Cash. But this was a music that I was consciously and deliberately unfamiliar with, so rather than telling you what I knew, I’m sharing with you what I discovered. And I discovered a new thing every single day of the eight and a half years we worked on it. I mean, you think about the racial components—how many of the early country music stars had an African-American mentor. That the banjo is from Africa. That this music is completely connected to the blues and to jazz and to R&B as well as folk and rock—of which it is one of the parents—and pop and even classical, and of course gospel music. Country music is not an island nation separated from everything else. The artists completely cross over, back and forth—black as well as white. Remember when Ray Charles had creative control of an album for the first time, he surprised people by coming out with Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, which had the Hank Williams classic “Hey, Good Lookin’.” For me, the film was an exploding of the unnecessary borders. Everything is porous, and artists understand that.

The contribution of black musicians, especially early on in country music’s history, rarely gets the recognition it deserves, and opportunities still aren’t equally distributed for everyone. In the film, stars such as Reba McEntire also discuss the disparity in opportunities for women. How did those obstacles reveal themselves in your research?

The much larger theme [that emerged] is that this supposedly “white” music is also black, and this supposedly “male” music is also very, very female. The original guitarist is Mother Maybelle. Everybody flows from her, including Eddie Van Halen shredding guitar. I think it’s always a struggle for a woman, just as it’s always a struggle for an African-American. You have to be that much better, that much more perfect, in order to get by. The bar is much higher. But the history of country music is a history of super strong women, and we rejoice in being able to tell that tale.

Photo: Courtesy of Carter Family Museum, Rita Forrester

The original Carter Family in 1930. From left: A.P., Maybelle, and Sara Carter.

For the earlier episodes, since you couldn’t interview country stars of the early 1900s, you spoke with musicians and historians. Did you anticipate how much today’s artists would be able to contribute to the historical conversation?

We actually have only one historian in the whole film. Out of a hundred and one interviews, only one is a historian. What we found out is that the musicians and the songwriters themselves knew their own music’s history and were great protectors of that history. Ketch Secor [of Old Crow Medicine Show], Rhiannon Giddens, Rosanne Cash, Marty Stuart—they’ve made a point of studying this, and they became our guides to the earliest point until we could get to people like Willie and Merle, who remembered Gene Autry or Ernest Tubb or Bob Wills.

We also really hoped that Willie and Merle and Rosanne and Marty would not only tell us what they knew about the history they so carefully curate, but would then segue into their own stories, and that’s exactly what happened. That’s good history. I mean, it’s priceless to watch Marty Stuart tell the story of being 11 or 12 years old, going to the Choctaw Indian Fair in Meridian, Mississippi, to see Connie Smith—who he thinks is the most beautiful person in all of country music—get a couple of photographs with her, and then declare to his mom and his sister on the way home that he’s going to marry Connie Smith someday…and he does!

Just that he was able to meet her at a fair—you see that personable quality in country musicians throughout. There’s an anecdote in the film about Gene Autry, that his wife kept a filing system of the names and addresses of the fans who wrote to him, and when he came into town, he would look them up and give them a call. I love that you included that detail.

This has been there since the very beginning.

Yes, the loyalty to and intimacy with fans.

And it happens again at the end of the film, too. Garth Brooks goes to a fan fair, and he hasn’t even been invited, but he signs [autographs] for twenty hours. You can’t do this with Mick Jagger. You can’t do this with Frank Sinatra. You can’t do this with Leonard Bernstein. But you can do it in country music. You can go up and say, “Hey, Willie, that was a great set.” Or, “Marty, I love you.” Or, “Kathy, I had to be here even though my mama died this morning.”

Photo: Courtesy of Amy Kurland

Garth Brooks at the Bluebird Café in Nashville in 1988.

Our last episode is titled “Don’t Get Above Your Raising.” It’s an old Southern thing that means “Don’t get too big for your britches. Don’t forget where you came from.” And country music stars don’t forget where they came from. As much as we want to dump on country music and say, “Oh, it’s just good ol’ boys and pickup trucks and hound dogs and six-packs of beer,” what it is really about are these poets who have crossed the last century, decade after decade after decade, writing about, talking about, singing about love and loss—and particularly loss. None of us gets out of here alive, so that sense of loss permeates the human experience. And I don’t know of any musical form that handles this better than country music.