Common Threads

Cross, catch, or slip, every stitch tells a story. Natalie Chanin, founder of the sustainable design company Alabama Chanin, created the nonprofit Project Threadways to uncover, preserve, and share them—both stitches and stories. “Textiles are so intertwined with many areas of the South, from the cotton fields to the sock and T-shirt mills now gone,” Chanin says. “Our textile stories—rich, complicated, sometimes brutal, sometimes beautiful—are disappearing, too.” Project Threadways’ 2023 Symposium (April 20–22), in Chanin’s home base of Florence, aims to keep those stories humming, with presentations and workshops. In one event, Viola Ratcliffe of Birmingham’s nonprofit Bib & Tucker Sew-Op will describe how quilting-centered programs have inspired a new generation. “I hope we motivate people to create their own art,” she says. “I hope we also spark a passion to find and support those doing good in this space.” projectthreadways.org

Back to Form

Technically Little Rock’s Museum of Fine Arts was completed when it opened in 1937, but some critics felt otherwise. A series of add-ons followed throughout the decades, lending the Arkansas Arts Center, as it came to be known in 1960, the architectural clarity of a poorly played game of Tetris. When the museum closed for yet more renovations in July 2019, the architects at Studio Gang took a different tack. In the newly rechristened $142 million Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, opening on April 22, a soaring light-filled central atrium links 133,000 square feet of exhibition, performance, and education spaces with eleven acres of land and gardens. Old meets new, inside meets outside. It’s only fitting, then, that one of the inaugural exhibitions, Together, reflects connections—among people and with the natural world. As curator Catherine Walworth says, those connections aren’t just between visitors; they apply to the museum staff as well. “It’s almost like an expression of our own longing to be back together with audiences and with art.” arkmfa.org

Line of Hope

When Hurricane Ian roared into Southwest Florida last September, the J. N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge suffered major damage to both buildings and wildlife habitat. Coming back will take years of resilience—like the kind that will be on display May 19 when the “Ding” Darling & Doc Ford’s Tarpon Tournament kicks off from the Sanibel Island waterfront. The one-day catch-and-release tournament raised over $1 million for the refuge in its first ten years. Named for a famed cartoonist and pioneering conservationist, the refuge was the site of the first recorded tarpon caught, in 1885 off Sanibel, by an angler using hook and line. Although the Doc Ford’s Sanibel location remains closed, the well-known restaurant vowed to continue the tournament. “That was a real morale boost to this community,” says Chelle Koster Walton, who works with the refuge’s Wildlife Society. “We need all the support we can muster down here.” dingdarlingsociety.org

It's in the Drink

During Masters week at Augusta National (April 6–9), the lucky few with access to the clubhouse will toast the course’s famous flowers with an azalea cocktail—a mix of vodka or gin, lemon, pineapple, and grenadine that serves as the tournament’s unofficial drink. Downtown Augusta bars follow suit; Craft & Vine on Broad Street puts on a weeklong celebration and keeps an azalea atop the cocktail list. “During the Masters, Augusta transforms,” says Breannah Newton, a director for Craft & Vine’s hospitality group. To bring the party home, shake up two parts vodka, one part lemon juice, one part pineapple juice, and enough grenadine to give the drink a pink tinge. Pour it over ice and top with a lemon slice. “It’s bright and refreshing and has a balanced sweetness,” Newton says. We hear it pairs perfectly with a pimento cheese sandwich. masters.com; craftandvine.com

Born and Bread

The historic Brown Hotel in downtown Louisville celebrates its centennial this year, but you might be more familiar with the spot’s namesake sandwich than its stately Georgian Revival exterior, marble floors, and hand-painted plaster ceilings. In 1926, chef Fred Schmidt invented the first version of a Hot Brown sandwich to appease hungry guests, who took advantage of a party band’s midnight break to refuel. The sandwich has become a Louisville bucket-list standard, especially around the Derby (May 6). “Two slices of Texas toast, two slices of bacon, seven ounces of hand-carved turkey breast, sliced tomatoes, all topped with Mornay sauce and served bubbly and sizzling in a ceramic skillet,” explains Marc Salmon, a director at the hotel who also serves as its unofficial historian. “Nowadays we serve Hot Browns for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.” brownhotel.com

Camellia Capers

Like memories, plants can be lost to time. “If they’re not cared for, they can disappear,” says F. Wayne Stromeyer, who along with his colleague Trenton L. James wrote the new book Early Camellias in Louisiana to document exciting rediscoveries of the South’s favorite winter flowers. “Often, no one’s keeping up with their names. Some camellias have been sitting here for two centuries, but no one knew what they were.” Traveling to historic sites throughout the state and conferring with garden experts, Stromeyer and James tracked down such elusive varieties as the bright crimson Chandleri at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Laurel Hill and the strikingly rosy Landrethii at the 1790s estate Butler Greenwood outside St. Francisville. “They were going around like detectives looking for flowers and forgotten gardens,” says Cybèle Gontar, an art historian who edited and published the book. The last of the season’s blooms can be spotted through March, and early spring is also the best time to plant camellias: Louisianans can find Lady Hume’s Blush, Professor Charles Sargent, and other old and rare varieties at nurseries such as Larry Bates Nursery in Forest Hill and Mizell’s Camellia Hill Nursery in Folsom. “There is a place for historic camellias in any garden,” Stromeyer says, “for those who are looking.” vellichorpress.org

Egging Them On

Come springtime, Tami Pearl will scour Maryland’s Assateague Island National Seashore, looking for piping plover nests. Some twenty breeding pairs of the petite shorebird—listed as threatened since 1986 because of coastal development and sea level rise—use the island year after year, arriving in March from as far south as the Bahamas to breed and lay eggs. When Pearl, a biological science technician who conducts the island’s annual avian population surveys, finds a nest, she builds a cage around it that lets in the birds but keeps out larger predators until the chicks emerge in May. “When they hatch, they’re like cotton balls on toothpicks,” she says. They leave the nest and roam the dunes and beaches with their parents, perfectly camouflaged and ready to deploy their best defense mechanism—standing dead still—if a parent pipes out a warning call. “One time, I saw a chick freeze mid-run, with one foot still in the air,” Pearl remembers. “And sometimes they dip down in a hoofprint from one of our horses.” To spot a plover on Assateague before they head south, Pearl recommends walking along the water (the interior beach is off-limits during nesting season), binoculars ready, and looking far ahead to see a sand-colored puff speeding off on orange legs. nps.gov/asis/index.htm

She’s Got the Rhythm (and the Blues)

In her song “She Shimmy,” when Libby Rae Watson, a blues singer and guitarist from Pascagoula, belts out, “Hill Country spirits, all in this hall, clock strikes midnight, we’ll be having us a ball,” she pays homage to the musicians who blazed a path for her. Names like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf have long been a part of the Mississippi blues collective memory, and now, thanks to music lovers in Clarksdale, the women of blues are getting their due, too. “There’s a special energy in this hub for the blues, community, and revitalization in downtown Clarksdale,” says Colleen Buyers, who with her organization Shared Experiences launched the Women in Blues Festival (May 19–20), now in its second year. Watson will open this year’s festival, followed by performances by Edna Nicole Luckett and LaLa Craig. “I was so happy that we blues artists finally have a space just for women,” Watson says. “In my fifty years of performing, I have never seen an event like this.” womeninblues.org

Family-Style Dining

Chef Sunny Gerhart has long been experimenting with pasta at his Raleigh restaurant, St. Roch Fine Oysters + Bar, and diners can try his top success stories when he opens Olivero on a cobblestone-lined corner of downtown Wilmington later this spring. His legacy will wind through the handmade pastas and paella inspired by his grandparents’ origins, and season the jambalaya influenced by his childhood in the Big Easy. “I’m learning more about Italian and Spanish food and what that means through a New Orleans lens,” Gerhart says. “And that just happens to be a part of my family’s story.” Gerhart dedicated his old-world-style restaurant to his mother and named it after her father, a sailor who immigrated to New Orleans from Seville and married into an Italian family. He’ll anoint the centerpiece of Olivero’s open kitchen—a wood-burning grill, visible from the intimate dining room—with juicy steaks and Carolina-caught fish. oliveroilm.com

A Silver (And Indigo) Lining

“Art teaches us about cultural contributors,” says Caroline Gwinn, executive director of the Aiken Center for the Arts. “Who contributed to South Carolina history and who is contributing now?” In the Interwoven exhibition (March 30–May 3), part of that answer lies with Kaminer Haislip, a Charleston silversmith who uses tools and processes that were popular prior to the Industrial Revolution. The work of Madame Magar, a Johns Island textile artist who grows indigo, unlocks even more history. On view together, their works reference early colonial times until the Civil War, when silver and indigo dominated markets. “I’m interested in art and craft that deals with a sense of place and history, but at the same time turns traditions upside down,” Magar says. Her palm-sized baskets woven with indigo yarn, and Haislip’s shiny coffeepot fitted with a purple heartwood handle, place historic processes firmly in the present. The artists joined forces to create self-portrait silhouettes, dyed on cotton by Magar and framed in delicate hoops forged by Haislip, the two mediums connected in time and, now, space. aikencenterforthearts.org

Character Study

In historic Fredericksburg, a cement elephant presides over 242 East Main Street, marking the original home of the White Elephant Saloon, built in 1888. That preserved marker is now just one of the protected treasures at the soon-to-open Albert Hotel. Fittingly named after the architect Albert Keidel, the new hotel pays homage to one of Texas’s most important preservation families, making soulful use of historic spaces—the saloon, the Keidel family home (built in 1860), an 1870 home, and the 1906 Keidel Pharmacy—sprawling across a coveted slice of downtown. “The hotel environment is a push-pull of masculine and feminine, historic and new,” says director of design Melanie Raines. At the Restaurant at Albert Hotel, one of three new dining options, a proper sit-down dinner might start with executive chef Michael Fojtasek’s amuse-bouche of chicken liver mousse on a potato roll, and end with a nightcap in the White Elephant room. alberthotel.com

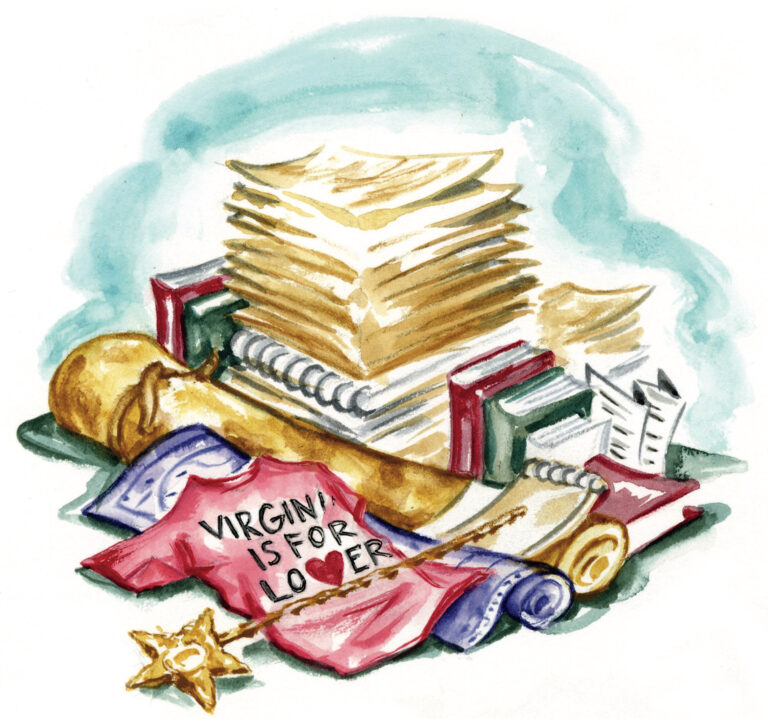

They've Got It All

For two centuries, the Library of Virginia in Richmond has served as the commonwealth’s unofficial Department of Hoarding, amassing more than 130 million records and artifacts, from governors’ papers to travel brochures to a magic wand. This year, the city-block-sized building celebrates its bicentennial with 200 Years, 200 Stories, an exhibition that sorts through the holdings to recognize hundreds of fascinating Virginians. Don’t come looking for Washington, Jefferson, and other founding fathers, though. “This is not about the who’s who of Virginia,” says Gregg Kimball, the library’s director of public services and outreach. Instead, the staff highlights notable but often lesser-known citizens such as Ethel Bailey Furman, the state’s first Black female architect, who designed about two hundred residences and churches in Central Virginia during the twentieth century. As for the wand, it belonged to Melanie MacQueen, who became a statewide celebrity when, from 1989 to 2013, she starred in Virginia Lottery commercials as a fairy godmother named Lady Luck. lva.virginia.gov/200

It's a Small World

Unless you’re a diplomat or leading a trade delegation, it’s not easy to snag an invitation to an embassy. “It’s considered foreign land,” says Victor Shiblie, publisher of the Washington Diplomat, which covers D.C.’s international community. “You’re entering a foreign country, basically.” But every May, Washington puts out a rare welcome mat to us commoners during the Around the World Embassy Tour (May 6) and the European Union Open House (May 13). In previous years, Indonesia has brought in food trucks, and Colombia has staged folkloric dance performances in its front yard. Other countries have offered rum, cocktail, and coffee tastings. culturaltourismdc.org

Go Your Own Way

The best route between two points isn’t necessarily a straight line. Some Appalachian Trail trekkers take a flip-flop hike, starting their adventure in the middle in Harpers Ferry, and walking 1,200 miles north. Once they summit Mount Katahdin, Maine, the traditional end, they catch a ride back to their West Virginia starting point. Then they hike another thousand miles south to finish where most people start, at Springer Mountain, Georgia. Harpers Ferry and nearby Brunswick, Maryland, celebrate the contrarian route with an annual Flip Flop Kickoff (April 22–23), with hiking-skills workshops and a communal high-carb breakfast to send adventurers on their way. Flip-flopping saves wear and tear on the trail—during March and April, thousands of people may clog the route near the Georgia starting point. Beginning in the middle helps hikers too, says Deb Coleman, a retired lawyer who completed a flip-flop thru-hike in 2017. Time it right, and you can avoid weather extremes, walking north in what can feel like perpetual spring, and heading south in mostly fall weather. “I like a certain amount of solitude on the trail, and that part appealed to me,” Coleman says. “I never had snow or freezing temperatures. And I only found a full shelter once, which is unheard-of.” The Appalachian Trail Conservancy began promoting the alternate routing in 2015, says Laurie Potteiger, who helped plan the first festival. But year after year, there’s still one misconception she must address: No one is advocating a hike in flip-flops. “You wouldn’t get more than ten feet.” flipflopfestival.org