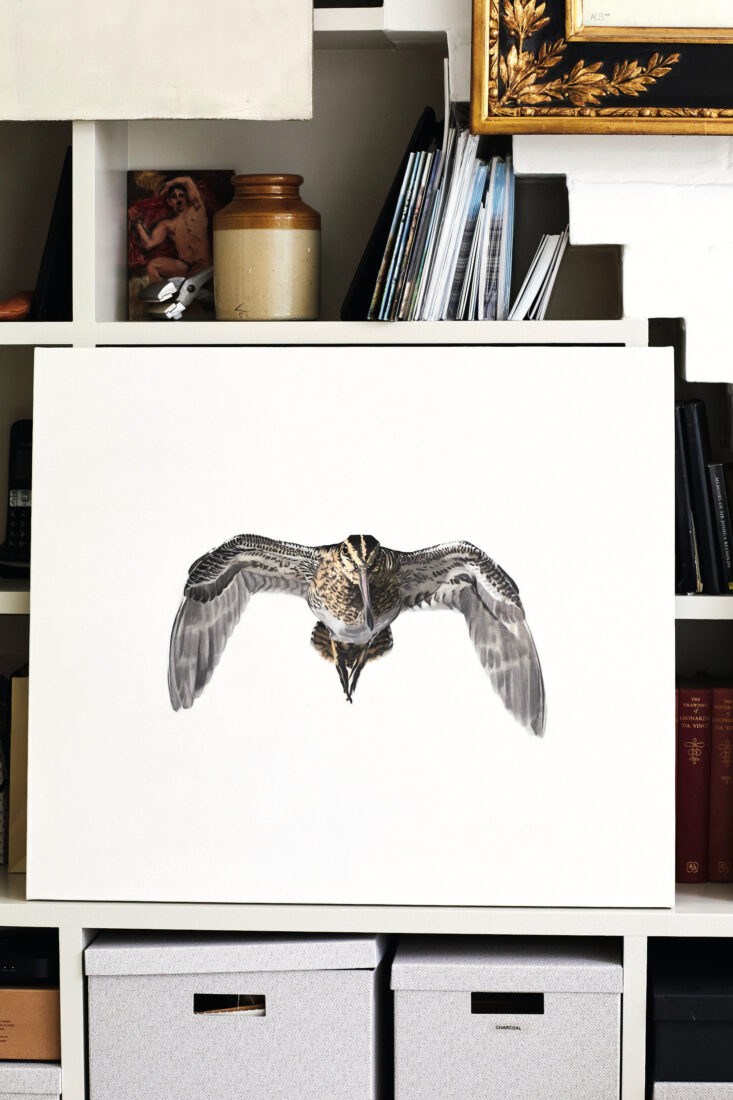

Just off Piccadilly, four blocks from the Ritz, London cabs sat stuck in a sudden standstill. Moments before, the Rountree Tryon Galleries had hung a new work by the thirty-six-year-old artist Anna Clare Lees-Buckley in the window, and passersby were choking up St. James’s Street, taking in the striking sight-size portrait in oils of a gray partridge in flight: the orange head, the rust-red tail, the split black circle of feathers on its silver breast, like a glinting oculus, against a stark white sky.

British culture has long celebrated the partridge, since even before mentions in Shakespeare’s plays and Henry VIII’s conservation decrees to protect it in the 1530s. But this painting doesn’t wallow in the romance of the foggy fields and moors, nor showcase the bird’s iconic status as game quarry, nor depict it as a table bird, as in the still lifes of the masters: Italian, Dutch, Flemish, and French, such as Chardin and Renoir.

Rather, the painting leaves all that behind. It’s about the bird itself, the populations of which have, because of habitat loss, pesticide use, and other human interventions over the past century, been knocked down across the United Kingdom from millions to possibly fewer than fifty thousand. It’s just a powerful, breathing thing, beating its wings.

“There’s so much movement and drama,” Lees-Buckley says of game birds, including the impeccably detailed, photorealistic portraits of grouse, snipes, curlews, and lately, birds of prey propped up on easels in her Chelsea studio. “It’s quite a hard thing to capture, but a tremendously thrilling thing to paint.”

Lees-Buckley grew up here in London—“an urban child,” she says with a chuckle—but many of her memories are of the British countryside. “My father is a very keen shot and angler, and he would drag us off, in our wellies, to the country on weekends and holidays and things, and sometimes you’d be shooting. I think that’s where my love for British wildlife came about, in those early years, jumping around in the mud.”

As a university student, she trained to become a painter. Then, over four rigorous years in Florence, she honed her skills in the naturalistic tradition of sight-size portraiture at the Charles H. Cecil Studios private atelier. But upon her return home, she was feeling a bit disenchanted with the craft—or was it the human face? Her father suggested she paint him a bird.

She found the challenge of capturing a bird in flight—say, a woodcock, silhouetted in a jewel sky—addictive. She paints from pictures, like those of photographer Tarquin Millington-Drake, known for his grouse and pigeon images. This also absolves her from the awkwardness of painting humans from life. “The pressure of someone sitting for you isn’t there,” she says, “which suits me quite well.”

Lees-Buckley’s approach to the details she includes is meticulous. For a time, she stretched her own canvases, as the Renaissance painters she studied in Florence would have, down to sizing the linen with rabbit-skin glue—a process more time-consuming and expensive, she found, than buying just-as-nice ones from the art supply shop. She does still exclusively make her own white paint, however, sometimes with a walnut oil, sometimes with a cold-pressed linseed. “I like quite a buttery consistency,” she says, surveilling the apothecary of colorful tubes, jars, and bouquets of brushes in her purpose-built, Victorian-era, live/work artist’s cottage. She made the move to Chelsea Studios just last year, in search of more room.

“My paintings kept getting bigger, and consequently, like Alice in Wonderland, the room kept getting smaller,” she said of her previous studio. “It’s quite a relief to have the two-and-a-half-meter-wide [painting of a] hen harrier flying toward you somewhere I could actually view it in landscape orientation.”

Before, she’d instead have had to tell visitors to imagine it right side up—and they would: Most of her works sell before they’re even completed, to an audience of shooters, collectors, and nature lovers alike who appreciate what’s at once a uniquely contemporary homage to the sporting tradition, and a nod to the importance of protecting threatened species.

For a painter who relies strictly on natural light, summertime brings long days. In fall and winter, she sketches when the daylight wanes, and this past February, she removed herself from London altogether, though not from her art: On Tierra Bomba Island, off the coast of Cartagena—as the artist in residence at a beach club called Blue Apple—she painted a portrait of one of Colombia’s 170 hummingbird species. There might not be as much drama in the hovering flight of a hummingbird as there is in the commanding swoop of a kestrel, but there is beauty—and some levity, and in great detail, she manages to capture that, too. “Sometimes,” she says, “there are things you see that just make you think, ‘I really want to paint that.’”