I got the news that a judge in Georgia had stopped the presses on my first novel, The Wind Done Gone, a parody and critique of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, while I was sitting on a nineteenth-century full tester bed, a massive thing with plantation provenance. The bed came to us from a white and undocumented side of my husband’s family. All involved enjoyed the unspoken joke that finally someone on the black side of the family could openly lie down on the bed instead of dusting it.

The bed quickly became my office of choice. And so I was sitting up in that bed when I got the call that told me my book was being suppressed by a judge in Georgia; and I was sitting up in that bed when I started looking at a stack of papers faxed to me from my lawyers, the letters and declarations of authors petitioning the court on my behalf, demanding that my book be set free.

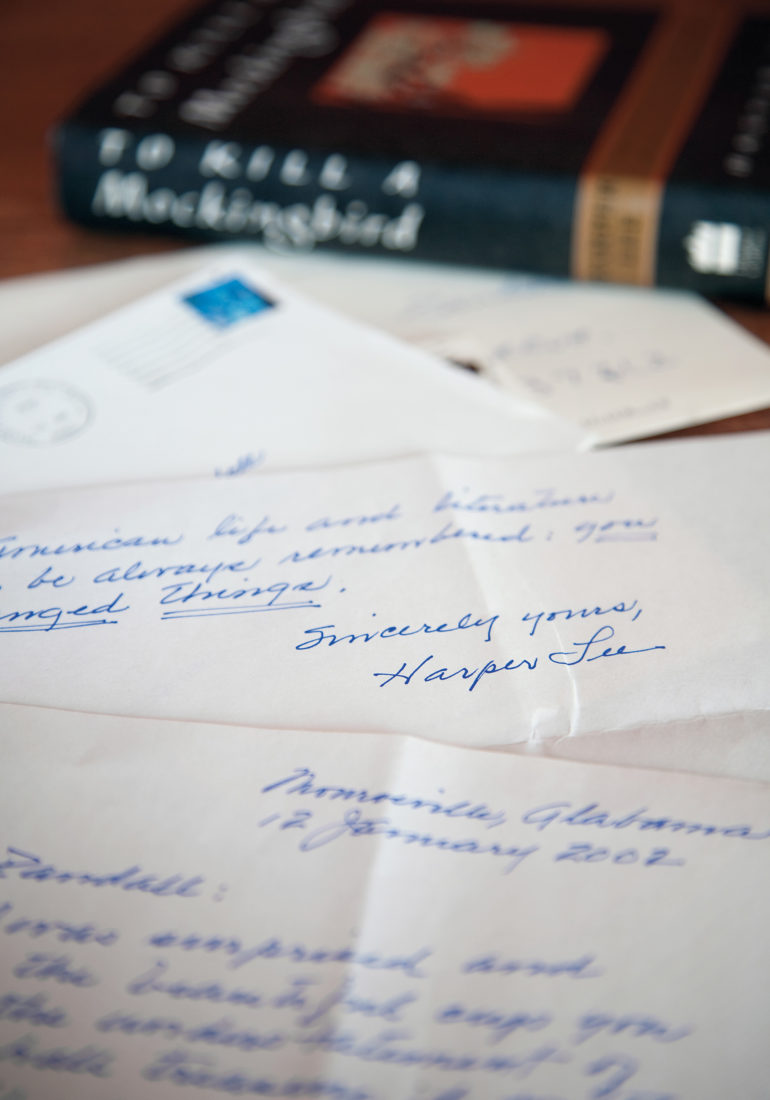

The names dazzled. Toni Morrison, Ishmael Reed, Pat Conroy, Shelby Foote, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., were among the signatures for my review. Eventually I came to a fax of a fax: a letter signed by Harper Lee. This signature carried the weight of To Kill a Mockingbird, Lee’s classic novel about race, redemption, and righteousness.

The court case in To Kill a Mockingbird is arguably the most famous fictional court case in Southern literature. Lee’s tale of the white Southern lawyer, Atticus Finch, burdened with defending a black man against a false charge of rape in a small Alabama town, spoke loudly to me in the moment.

As I read it, an older white Southerner was telling a younger black Southerner to get up and go to court whether or not she got justice. Even before Lee got involved, I had started thinking of myself as a character from her novel—the falsely accused and scared Tom Robinson. Now I was Tom and Scout, and Lee was Atticus and Boo Radley, the reclusive neighbor who turns out to be a rescuer.

A few weeks later (after excellent lawyering by a team from the Atlanta-based firm Kilpatrick Stockton) a three-judge panel on the Federal court of appeals freed my book on May 25, 2001.

By June, The Wind Done Gone was on the New York Times best-seller list. Around our house it was a subdued time—in part because I was going on book tour with guards in response to threats, in part because my daughter was being subjected to racist commentary about my book from a schoolmate. Most of it was due to the fact that my husband’s grandmother had died in the days between when the presses were stopped and the book was published. Corinne Steele had hated Gone with the Wind. I hated knowing she had returned to the red Alabama clay thinking I wasn’t going to be allowed to tell how we felt about Mitchell’s work.

The day that pall began to lift, I was opening mail when I came across an extraordinary thank you note. I had sent Ms. Lee a julep cup to thank her for writing to the court on my behalf. Here was a letter from her on plain white paper thanking me for the gift. The ink was blue and the script was fine. “What you did took the rarest kind of courage; it won you the respect of all people of good will. To go against the merely popular version of a cultural era is one thing; to take on a much-clung-to myth is awesome, like re-writing The Iliad.”

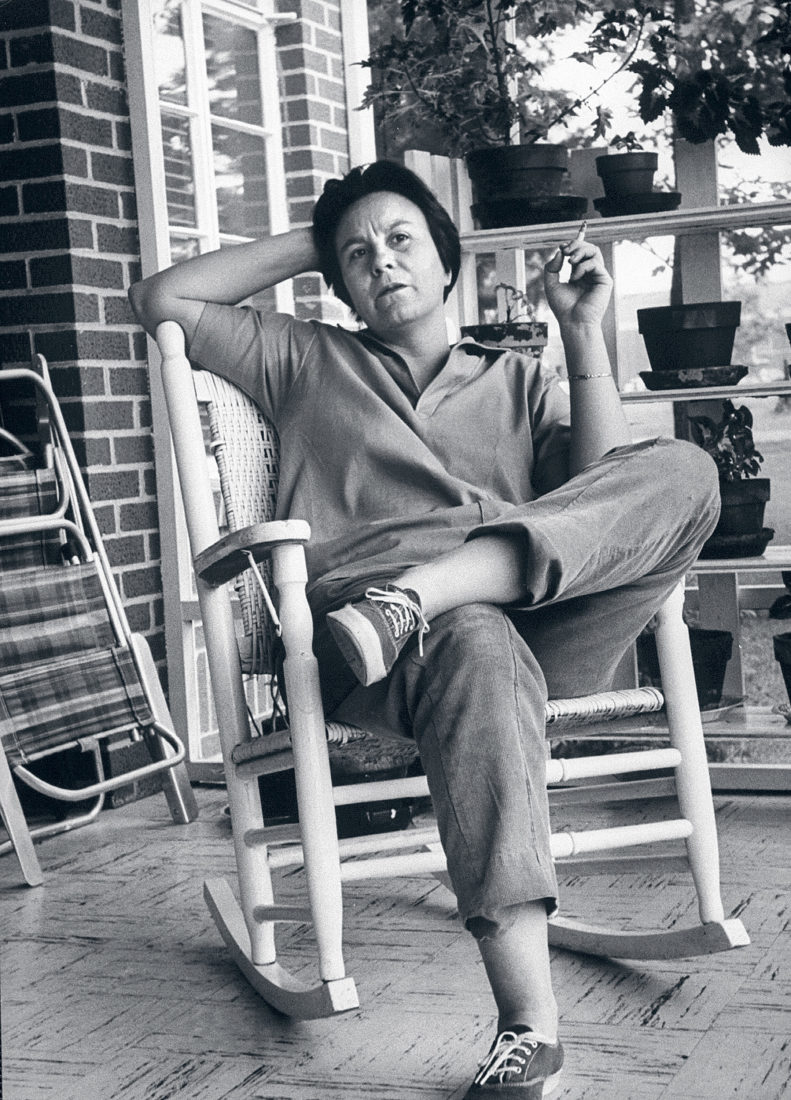

Photo: Caroline Allison

Strong Words

Some of the letters from Harper Lee.

She was proud of her part in the victory and she said so. “I am reminded of the ordeal you underwent and its triumphant outcome, and I am filled with pride that I played even just a small part in it.” I was stunned by both the generosity and the humility of the woman. And I was struck by the Southernness of the letter. The mix of fine manners and politics, classical allusions and familial references, was true Dixie.

There are so many ways to read and admire To Kill A Mockingbird. One approach is sometimes overlooked: Mockingbird functions as an etiquette book. And manners matter in the South. Down here Harper Lee is a great Southern lady, and down here we know that being a Southern lady is a high and particular calling. Lee is someone who cannot be ignored—a polite, quiet, and intelligent call to consciousness. So much of what she has to say about brothers and summer and Lane cake makes so much sense that you know that what she has to say about black people and courthouses makes sense too.

Back in the late nineties, I suggested Mockingbird for a mother-daughter book group that my daughter and I helped found. Together an integrated group of five mothers and five daughters discovered and rediscovered the truths of Lee’s pages: that Lee realized that black men could be desirable, that white women could be liars, and that girls were bold and curious. We noted how much more intelligent the domestic servant in Mockingbird was than Mammy in Gone with the Wind. We noted that the town drunk only pretended to be drunk so he could get away with loving a black woman. We learned that having a daddy who practices civil rights law can be terrifying.

When we had finished, my daughter wrote a series of poems in homage to Lee. One of the mothers baked a Lane cake. We started dreaming of a field trip. I will never know what Harper Lee would have done if we had shown up uninvited on her doorstep with a Lane cake and five eleven-year-old girls. I know that when I showed up in her life as an accused plagiarist, she stepped into the hullabaloo that engulfed me to stand by my side.

I will always be in her debt. Not because she wrote to the court and then exchanged six letters with me over a decade. Before she knew of my existence, I knew of hers. Her words made me braver than I might have been from near to my very beginning.

I was born in 1959. Mockingbird was published in 1960. I read it for the first time not long after reading Gone with the Wind. I have long divided the world into Scouts and Scarletts—and I have always wanted to be Scout.

And for every year of my life but the first, Mockingbird’s very existence, reader by reader, thirty million strong, has made the world a better place for me and for mine, just as before I was born and for every single year of my life Gone with the Wind has made the world more difficult for people like me.

If my house were on fire, my letters from Harper Lee, one on white paper, two on fine board stationery with her monogram, would be among the treasures I toted to safety. Without proof, even I would cease to believe they exist.