Before he even reached the cases of shiny silver dishes and booths of vintage state plates, Daniel Barrett Mathis spotted the strangest hunk of pottery near the door of the I-44 Antique Mall in Tulsa. The vase looked heavy and its colors shocking, heartbeats of red paint dripping into swirls of green-blue, orange, and black. He couldn’t decide if the piece was fabulous or charmingly ugly.

“I hadn’t seen anything like that before, and it’s not like anything else I have,” says Mathis, whose Instagram handle @NotaMinimalist hints at the incredible number and scale of his collections—hand-carved walking sticks, seashells, vintage beaded fruit—arranged artfully in his Oklahoma City home. “But I kept walking back over to that pot—and then I just went for it.”

Almost eight years later, his collection of the colorful vessels known as Ozark Roadside Tourist Pottery has reached some 150 pieces. Mathis became a student of the works, first created in the 1930s by a potter named Harold Horine, who aimed to capitalize on the rush of drivers exploring new roads into the Ozarks by hawking his slam-on-the-brakes souvenirs from his front yard near Hollister, Missouri. There, Horine spun and shaped a mix of sand and cement into planters and vases, and drizzled and dripped pigments on their still-drying surfaces. He eventually patented the method and franchised it to roadside stand operators from Texas to New Mexico to Oregon. Bright Ozark pottery lined the Missouri exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and when National Geographic chronicled the rise of the Ozarks in a 1943 issue, the story included a photograph of Horine glazing a pot that looks strikingly similar to the one that first caught Mathis’s eye.

Mathis has purchased the pottery from Etsy, eBay, and antique shops all over Oklahoma, Texas, and beyond. He thought his collector bubble would burst when he spotted one on a shelf in Kendall Jenner’s bathroom in Architectural Digest—luckily, the caption provided no information about the pot, keeping his prices safely low for a while. But in the past few years, perhaps because of renewed interest in American folk art and early-to-midcentury material culture, pieces that at one time sold for a couple of crumpled bucks might now fetch a few hundred online or at auction.

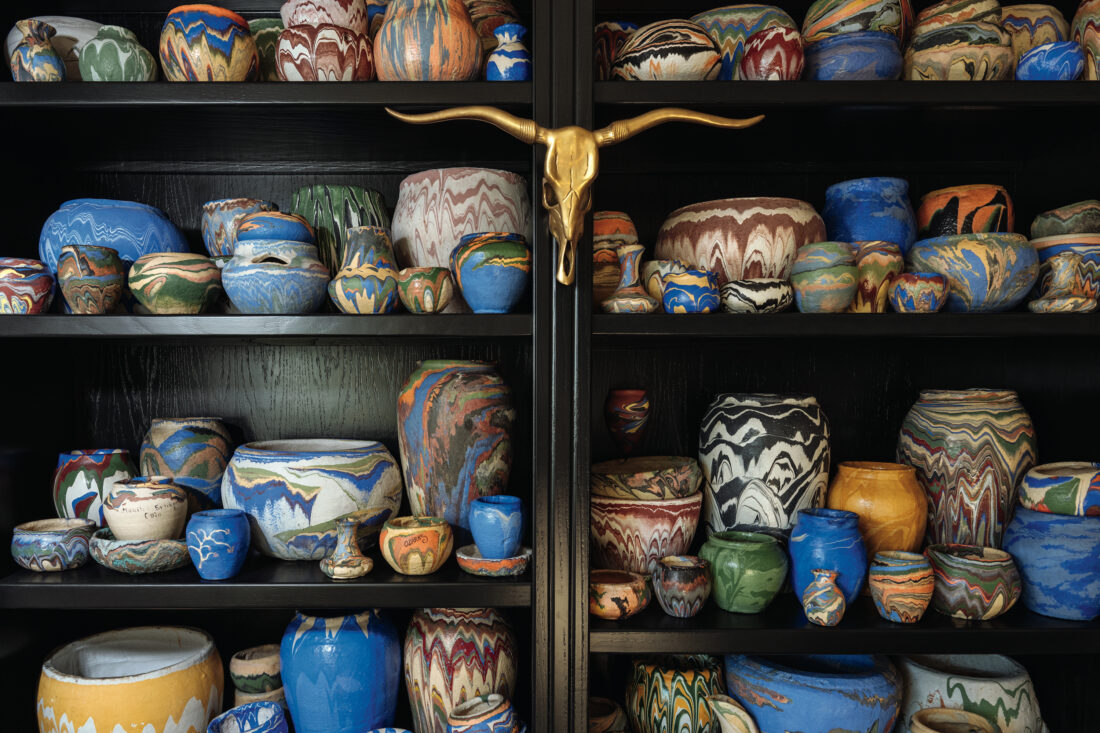

In Mathis’s own home, rather than decorating with little vignettes of paintings and objects, he groups his stand-alone collections to make powerful graphic statements. Rows of all-white McCoy pottery evoke a modern art installation, and he arranged the Ozark pieces to look like a rainbow cascading up and down tall, dark shelves. Maximalists, Mathis clarifies, are not the same as hoarders. “People might be surprised at how anal I am, the thought that goes behind placing a taller piece here and grouping a balance of colors over there,” he says. “And there’s no easy way around it—I dust a lot.”