It’s no secret that most of today’s commercial flowers, grocery store roses included, lack the scent they held in yesteryear. Instead, they’re like what I call “winter tomatoes”—beautiful on the outside, but disappointing otherwise. It’s not that the blossoms smell bad; it’s that they smell like nothing, as though they might be the products of a 3D printer or some other futuristic contraption that eliminates craftsmanship and soul. Fortunately for Southern garden lovers, the flower border at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, in Charlottesville, Virginia, preserves blooms prized for both their fragrance and beauty for future generations of the public (and home gardeners) to enjoy.

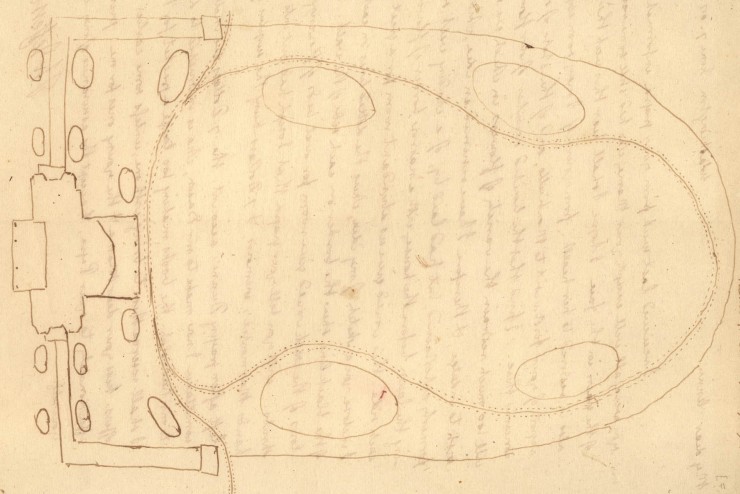

Monticello’s curator of plants, Peggy Cornett, oversees all things growing in and around the grounds and gardens of Jefferson’s home, among them flowers with a remarkable aroma. “Thomas Jefferson considered fragrance to be of equal import to beauty,” Cornett says. “In 1811 he wrote to the Philadelphia horticulturist Bernard McMahon: ‘I have an extensive flower border, in which I am fond of placing handsome plants or fragrant. Those of mere curiosity I do not aim at.’” According to Cornett, some of the plants he grew included sweet acacia (Acacia farnesiana), which the third president described as: “The most delicious flowering shrub in the world”; the fragrant caracalla bean (Vigna caracalla), in his words, “the most beautiful bean in the world”; and sweet peas (Lathyrus odoratus) and mignonette (Reseda odorata grandiflora).

In response to the letter from Jefferson, McMahon sent the president double tuberoses, the most aromatic of all the tuberoses (and that’s saying something, since nearly every modern perfume includes a note or two from varieties of this bloom). Jefferson also shared his love of flowers with a heavenly scent with France in 1786, sending seeds of the heliotrope with a missive that read: “a delicious flower…the smell rewards the care.” Another Philadelphia horticulturalist, William Hamilton, contributed to Jefferson’s passion, too, sending him mimosa (Albizia julibrissin), with the suggestion he cultivate it in pots to trigger the growth of flowers with intense fragrance.

For those looking to bring a bit of Jefferson’s sweet-smelling garden to their growing zone, many of the flowers mentioned above are available through the historic foundation’s seed and plant program, in Monticello’s online shop.

Haskell Harris is the founding style director at Garden & Gun. She joined the title in 2008 and covers all things design-focused for the magazine. The House Romantic: Curating Memorable Interiors for a Meaningful Life is her first book. Follow @haskellharris on Instagram.