She emerged, as beauty sometimes does, in the wake of an ugly moment.

Young marriage. Stupid argument. I slammed the door to walk it off in the Alabama night. As I stomped through the moonlit neighborhood, I heard footsteps in the street behind me. A black-and-tan puppy bounded up and licked my salty cheek. I went back home with a lighter step and a warmer heart.

“I think we should get a dog.”

The next morning, we were sipping coffee on the couch and watching the morning news when the Pet of the Week came on, an armful of a different black-and-tan puppy. Her name was Reba. We sprang up and drove straight to the shelter, where they gave us a funny smile. “Reba’s not back from the studio yet.”

In the visiting room, Reba cowered in a corner and wouldn’t meet my eye. By and by, she closed the gap and put her tiny paws on my shins. We decided to think it over. As we left, a nun with a cat in her arms caught my eye with a wink and a whisper.

“I think that’s your dog.”

* * *

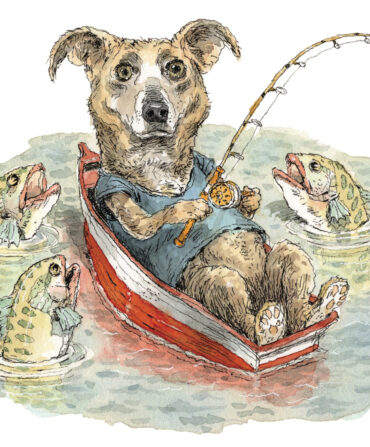

Reba was a dog with the soul of a fish. The sight of water made her vibrate. She loved swimming in ponds the color of lattes, among the blue-lagoon swells of the Gulf of Mexico, through eddies as clear as moonshine. She would race down a long, thin ribbon of dock to leap into a brackish bayou. She endured rides on a stand-up paddleboard with the dutiful restraint of a dog putting up with a treat balanced on its nose.

She knew her name, but it didn’t quite fit a dog that wasn’t a redhead. We thought about changing it. She ruled that out on a walk through downtown Nashville, where she abruptly sat, looked up, and wouldn’t budge. We followed her gaze to a billboard. A portrait of Reba McEntire.

Hearing this story, our Slavic friends offered a solution.

“In Serbo-Croatian,” they said, trilling the r, “‘Riba’ means ‘fish.’”

Riba could fetch a ball with the skill, precision, and style of an Olympic athlete, sprinting full throttle and catching it with a flourish, but heaven was a stick hurled into a lake. If it sank, she’d plunge her whole head underwater. If there wasn’t a stick to be found, she’d bite the branch of a fallen pine and drag us the whole damn tree.

Once, my husband walked her on a trail by a swamp where a cottonmouth raised its head. He threw a stick at the snake to scare it off. As the stick helicoptered through the air, he realized what he had done. “No!” he screamed in a panic. “Stay!” Good thing she was obedient. That might have saved both their lives when I later heard the story.

She loved afternoons at the water-ski lake, where I carved around the buoys of a slalom course. She’d race along shore, chasing my arcs of spray, and when I fell, she’d paddle out to save me. Riba’s face in repose was solemn, with lugubrious brown eyes that caught the light like wet river stones. But whenever she was swimming, her mouth curled into a smile.

When a baby disrupted her world, she sniffed his head and accepted him with a quiet resignation that slowly grew into love. She learned to dodge tail-grabbing hands and hover under the high chair, where it might rain bits of food. When the boy dressed up as Luke Skywalker, Riba endured the indignity of a Yoda costume with the stoicism of a Jedi. On the drive to a new home in Idaho, they napped together in the back seat.

As the boy grew older, so did she. As he grew stronger, her strength began to fade. On walks, she no longer pulled at the leash, but stopped two blocks away from home, ready to go back. One day, the boy threw a ball across the yard, and she watched it thud into the grass. For the first time in fifteen years, it lay there. Unchased.

* * *

We were canyoneering in Utah’s Zion National Park when our dog sitter called in a panic. Riba was sick, unable to walk. We cut our vacation short and worried the whole ten-hour drive.

When we got home around midnight, her tail wagged weakly. Her eyes stuttered back and forth, like a dizzy child just off a merry-go-round. Her head was cocked, and her body listed to one side. The vet gave her medicine and a week to see if it did any good. When it didn’t, we set a date for a vet to come out to the house. The Fourth of July. My father’s birthday and the date we had poured his ashes into the sea. The Fourth of Goodbye.

Two days before, we took Riba for one last swim.

The Snake River begins just inside Yellowstone National Park, winds through Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and bows through southern Idaho ahead of joining the Columbia. It got its name from the Shoshones, who identified themselves as a people who live near a river filled with fish. Trying to introduce themselves to white explorers, the Shoshones undulated their hands—their sign for “fish.” Those who saw the motion thought it meant “snake.”

We took her to a quiet bend of the Snake that flowed past an archaeological site where twelve-thousand-year-old petroglyphs tattoo boulders unleashed by an Ice Age flood. Riba by then could not walk, so I carried her into the river and held her in the gentle current. As her legs moved through the water, the heaviness lifted for a beautiful moment, the river aglow in the day’s last light. It felt like a baptism and a last rite. The final swim of a dog named Fish in a river misnamed Snake.

The next day, while Riba slept quietly, I took my son to witness a totem-pole blessing at Shoshone Falls, a sacred gathering spot for Snake River salmon. We encircled the five-thousand-pound pillar, fashioned from a four-hundred-year-old western red cedar by Lummi Nation carvers. I placed my palms on the totem pole and tried to muster a blessing. The only prayers I could summon were “please” and “thank you.”

In Riba’s final hour, a song sung by the Lummi carvers echoed through my mind: “Remember / we love you / we let you go to the other side.”

At that moment, a kind-eyed, white-bearded vet was leaning over Riba, filling a syringe.

“Do you have any pets?” I asked him, trying to steal one more minute.

As he answered, I snipped a few of Riba’s locks. I placed my palms on her body, memorizing the curve of her ribs, the softness of her fur, the rise and fall of her breath. I tried to give her a blessing. Again, the only words that emerged were “please” and “thank you.”

Blinking through tears, the needle poised,

I met the vet’s eyes. “What was the name of your dog?” He smiled kindly and answered with a gentle voice.

“Snake.”

We wept as Riba’s eyes turned opaque. Like river stones left to dry.

After months of growing accustomed to the void in every room, I pulled out a sachet of Riba fur and held it in my palm. Her dust bunnies no longer haunted the stairs, and the rug had lost her smell. Bending over my fly-tying vise, I wove her into a caddis fly, adding wings of hair from my son’s first elk and strands of my own long locks. One day we’ll go to the river again and wait for a fish to rise.