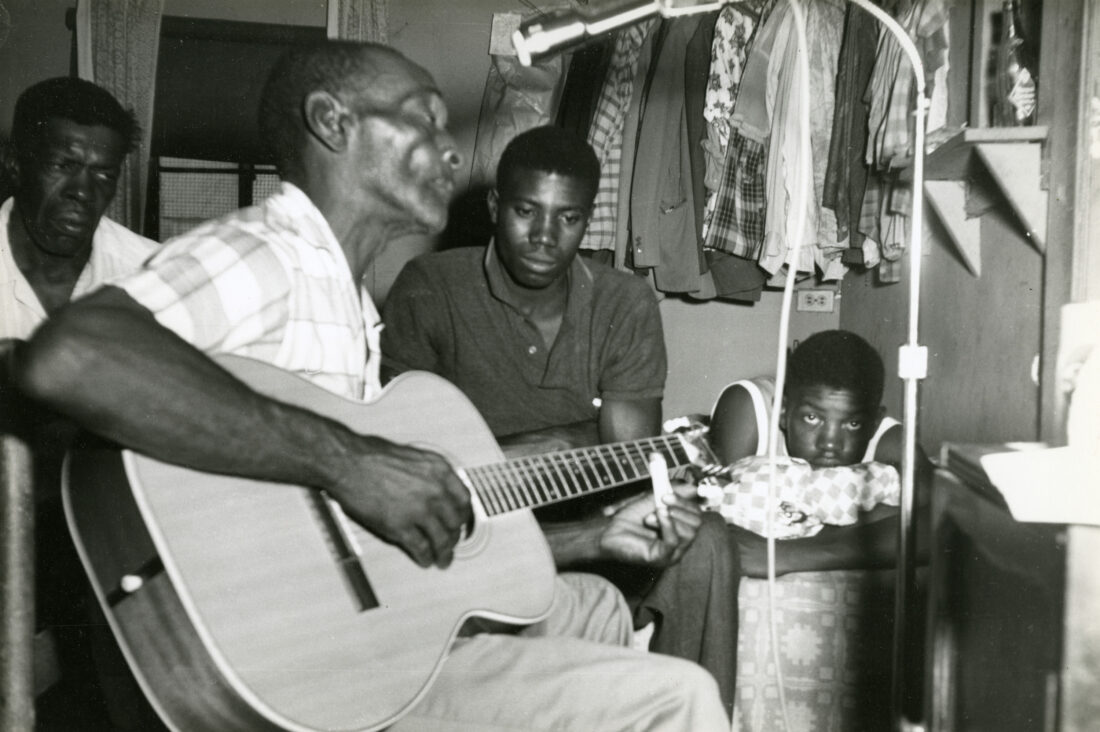

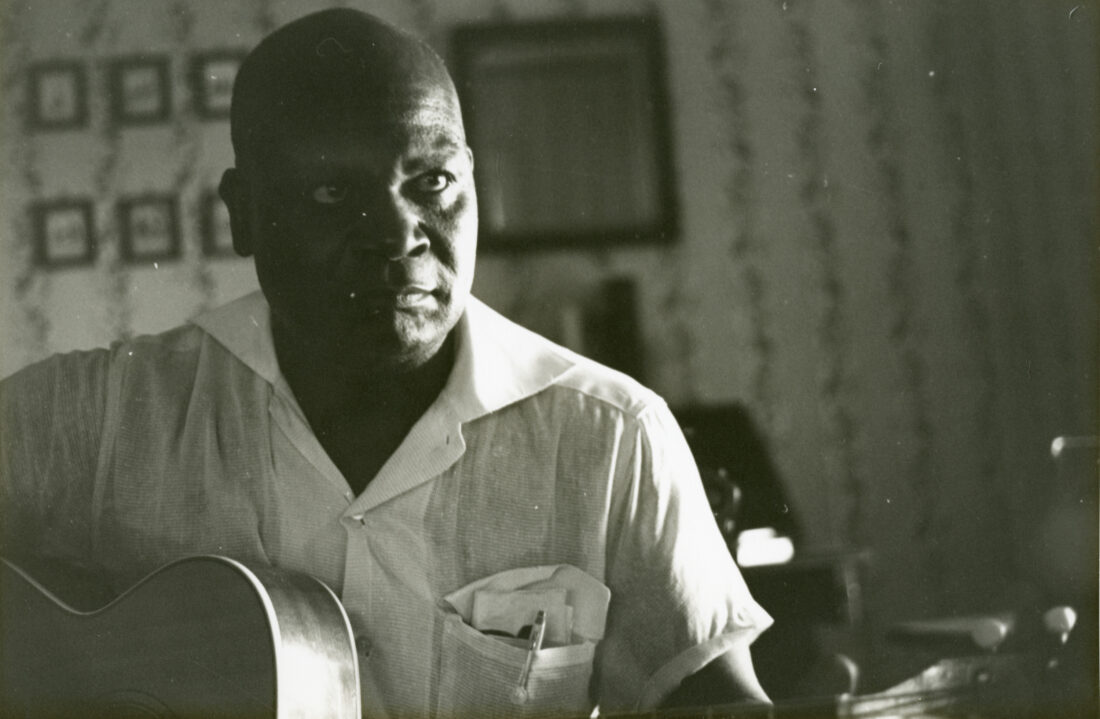

In the annals of music history, Robert “Mack” McCormick will go down as one of the most important chroniclers of the blues. Born in Ohio, McCormick was a music fan from an early age, hustling for local radio stations and becoming a respected jazz critic. Eventually, he settled in Houston and, in the 1950s, became an obsessive researcher and documenter of Texas blues, crisscrossing East Texas, Western Louisiana, and well beyond. As a folklorist, McCormick amassed hundreds of hours of field recordings and interviews with blues players along with more than 4,000 photographs and other music ephemera. He dubbed his collection “The Monster,” and it filled entire rooms in his Houston residence. McCormick was extraordinarily possessive of the material during his lifetime, to the point of paranoia (he reportedly stashed some of the more valuable pieces at a secret spot in Mexico). But a few years after his death in 2015, his daughter Susannah Nix donated the Monster to the Smithsonian Institution.

Now, those recordings are available to listeners for the first time. Smithsonian Folkways has just released Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958–1971, a sixty-six-track box set of previously unheard music from McCormick’s archive and the most comprehensive collection of Texas blues music to date. The set, which includes an accompanying book of photos and essays, contains songs from familiar names like Lightning Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb along with obscure artists such as Joe Patterson, one of the last known players of the quills (a series of bamboo pipes held together by string). “The first thing that stood out to me was how many performers I didn’t know about before getting into the material,” says Dom Flemons, the renowned multi-instrumentalist and founding member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, who penned a section of the box set’s liner notes. “The music is revelatory in that way.”

Many of the artists McCormick found came via word of mouth. In 1960, he took a job as a census taker, explicitly requesting to cover the Fourth Ward in Houston, a historically Black neighborhood where families settled in the late nineteenth century. After asking the official questions, he would inquire if the respondent played the blues or knew anyone who did. Along with the music, snippets of the interviews McCormick conducted are included throughout the collection. “It gives the sense of the sort of care he took in getting the recordings from each of these different performers,” Flemons says. “He went into this as a fan of the music, not someone who was looking to get rich.”

McCormick struggled with mental illness throughout his life; his eccentricities could be all-consuming, hence the Monster’s size and unwieldiness. He spent decades working in fits and spurts on a biography of Robert Johnson, an edited version of which was finally published earlier this year (and still worth a read).

McCormick was well known among music scholars, achieving a mythical quality, but the recordings are a must-listen for any music fan, expert or casual. As Flemons writes: “Playing for the Man at the Door is a reminder that we still have a lot to learn about the blues.”

Listen to a sampler of music from the box set below. Playing for the Man at the Door is out today, August 4, and available here.

Matt Hendrickson has been a contributing editor for Garden & Gun since 2008. A former staff writer at Rolling Stone, he’s also written for Fast Company and the New York Times and currently moonlights as a content producer for Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Service in Athens, Ohio.