With a retro sixteen-foot travel trailer named Lucy and an armful of watercolor supplies, Wyatt Waters set out to paint thirteen hundred miles across the South. For the sixty-eight-year-old painter from Clinton, Mississippi, working from life is non-negotiable. While some artists use site sketches or photo references, getting as close to his subject matter as possible fueled his cross-country journey to better understand the region. “I was always trained to work on location,” Waters says. “When painting on-site, you’re not working from a version of life or an opinion. Your subject talks to you.”

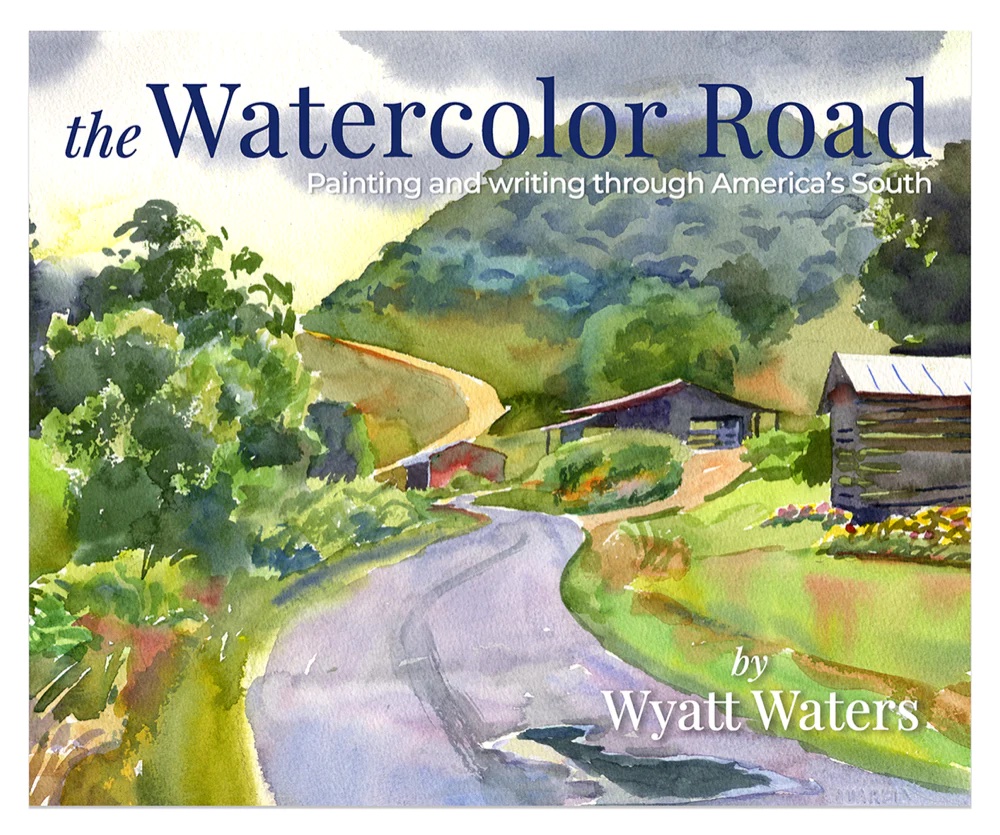

The resulting new book, The Watercolor Road, shares plein air watercolor paintings from Waters’s trips to nine states. Some scenes depict iconic landmarks, like Charleston’s Rainbow Row and the gigantic roadside Peachoid in Gaffney, South Carolina. Other pastoral scenes, including a cypress-filled Louisiana bayou and the sunlit mountaintop lookout at the Cross in Sewanee, Tennessee, focus on the natural beauty of the rural South. Waters’s and his wife’s loose itinerary, which left room for impromptu painting sessions, allowed time for the ordinary roadside scenes that sparked inspiration and called for a stop—even if it meant pulling up an easel to a misty Mississippi creek and painting in the rain while holding an umbrella.

“A lot of who I am comes from looking,” Waters says. “I go out to paint, but I have no idea what I’m gonna paint. Everything looks better on a quarter tank. Growing up, when I was little, we would pile in the car on Sundays and drive around: We would see whose barn burned down or who had a newborn calf or who was adding onto their house. We would just look.”

Traveling and painting had always been a dream of Waters’s, but it wasn’t a reality until he drove to Johnson City, Tennessee, in 2020 to pick up his Casita camper. Waters saw the opportunity to finally take to the road with his wife, Kristi, exploring and painting the region while safely weathering the pandemic. The two didn’t have every single stop planned out to perfection, but grasping a better understanding of his home place was Waters’s guiding principle. “There’s a one-dimensional idea of the South,” he says. “I wanted to create something more three-dimensional. My family has been here [in Mississippi] for seven generations, before it was even a state. I didn’t want the South to be a cartoon—it’s more interesting than that. I had to go to the source.”

For Waters, keeping an open mind on the road was essential: “If I said too much about what it was I wanted to discover, I wouldn’t be discovering it.” Below, the artist shares a little more about his passion for watercolor, how he names his paintings, and the best meal he had on his road trip.

Watercolor Road combines your artwork and journal entries. Were you always writing on the trip?

I’ve always kept journals; writing and painting have been tied together my whole life. When I was real small, my kindergarten teacher taught me to read using painting. Sometimes I’ll write in the morning about what happened the previous day, or whatever I’m projecting to do, or thoughts I’ve had about something that happened in my life. A lot of them go back to painting, that’s my primary thing.

As a medium, watercolor requires a lot of commitment. It’s not the most forgiving.

I love watercolor, it’s like going on a date. It challenges and engages me, and I always want to go back to it, even though it’s more difficult. It’s a challenge that I never really solve. I enjoy that process of going to battle with it.

Did you have a favorite state to paint?

I like the Carolinas quite a bit. I like getting lost, getting off the main highway, finding all the waterfalls and views, waking up and seeing all that fog. I loved Asheville; people were so nice. When I work outside, sometimes people are suspicious of me or want to run me off. In Asheville, they’re open arms for buskers. When I asked if I could paint outside of a shop, the manager came to check on me and see if I was doing okay—I wasn’t used to that kind of welcoming.

But I like the Florida Keys, too. I had never been there before. Even though it’s the most southern tip of the Southeast, it’s more like northern Cuba. It has a different culture.

Your paintings in Watercolor Road have funny titles. How’d you come up with those?

I used to show with a gallery for a long time, and they never let me title my paintings. I just make things up that are fun and mess with logic. Sometimes they’re puns, riddles, or song titles. Reading is a mechanical thing that leaves you with images. At Looking Glass Falls [in North Carolina], I made a painting I titled Falls Alarm. There are so many stories about people at the top of falls who get too close to the edge, and that happened the day I was painting.

Did you have a favorite meal on the road?

There’s a place in Raleigh with hot wieners called the Roast. It was the best hot dog I’ve ever had, and it’s been there for seventy-eight years. It’s a hole-in-the-wall that just serves hot dogs, and I heard so many stories about the place. They only do them one way, that’s the way they do it.

You sought to understand more about the South through painting. What did you learn from listening to Southerners you met across the country?

Everywhere, people are people. You can’t really know that until you’ve gone there and been there with them, talked with them, had a sandwich next to them. I’ve been to Italy a few times, and I painted there for a year. People from America would come up to talk, and I would say I’m from Mississippi. They looked puzzled, like they never would have thought that. People have assumptions about places. I asked if they had ever been there, or if they had only seen it on TV.

My mother is gonna call in a second—she’s ninety years old—and she tells the same stories over and over with some variations. That’s Southern literature. When you sit down at dinner and tell a story, you might make some changes. Maybe it’s not factual, but it’s in spirit true. You have to speak in metaphors and speak in stories. That’s how the great truths are told.