Rolling down the highway on my way to hunt some birds and what could be finer than that? Actually, things could be a little better. The Atlanta airport and a nameless airline might, for instance, not have lost my shotgun. I had waited around the airport for three or fours hours and finally decided the hell with it. Someone at the lodge would have a spare.

Now I am headed west, across the waist of Alabama, and my mind is on other things.

This road, for instance. Highway 80 is the route that some six hundred protesters took on a fifty-four-mile march from Selma to Montgomery. They were marching for the right to vote, which was still pretty much a notional thing for blacks in Alabama in 1965.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

This Is Quail Country

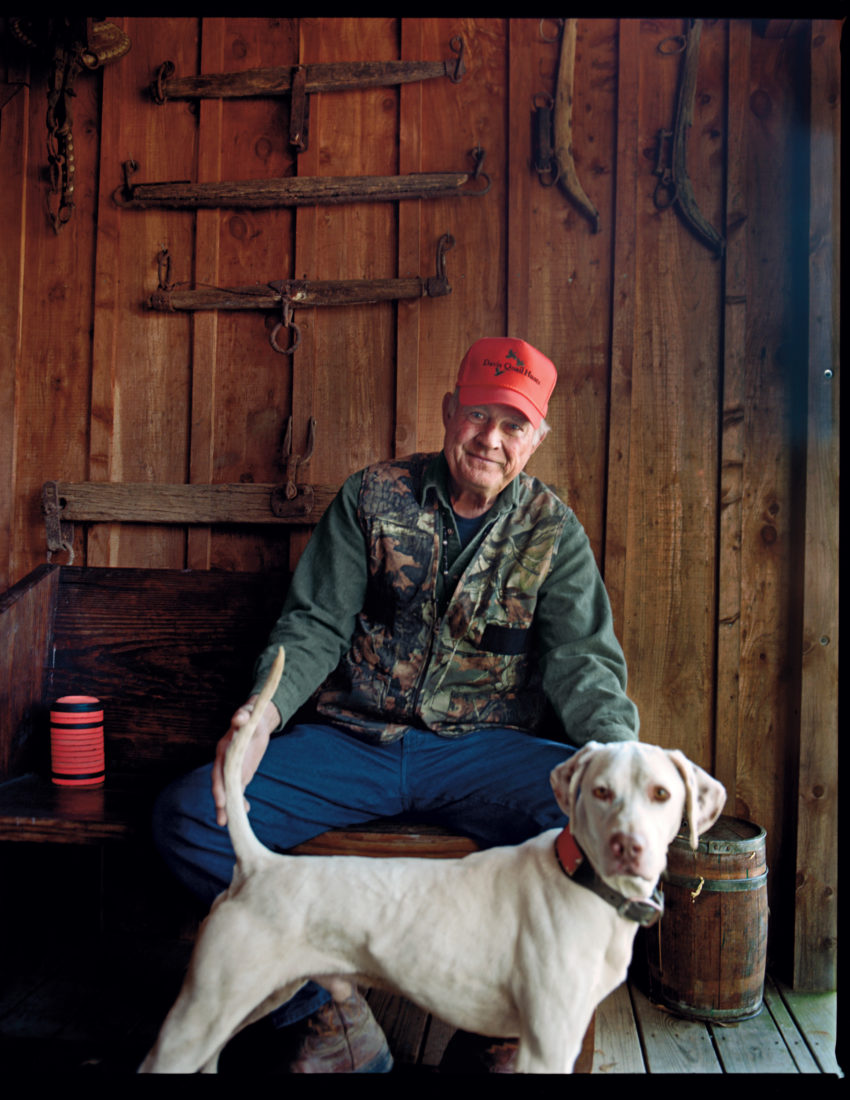

Owner Tom Lanier at Shenandoah where they typically hunt on horseback.

Much has changed since then and vastly for the better. Still…as you approach Selma the scene is one of neglect and abandonment. Shotgun houses with boarded windows. Rows of depressing project homes—empty now and gutted. Concrete buildings that were once bars or rib shacks and are now just empty eyesores. The neglect and the poverty are as palpable and oppressive here as they were before the clash at Edmund Pettus Bridge. Worse, actually, since so much of the rest of the world has moved on and prospered. They make automobiles in Alabama these days. But not here. In the Black Belt, poverty still rules.

I’ve been invited down to learn how an effort to promote bird hunting might help improve things around here. And having never, in my life, turned down an invitation to go bird hunting, I am not about to start now.

So I drive on through Selma, west toward the Mississippi line, and then turn off the main highway. Another turn and the road is now dirt. The dwellings are small and rough. Then, I come to the drive that leads into a hunting lodge called Cottonwoods where I am expected and where I will hunt birds and spend the night.

The lodge is rustically handsome, but that’s not what draws your attention. If you are a sportsman, you will find yourself looking—with lust—at a forty-acre lake with the banks grown up in the kind of cover that you just know hides large, belligerent bass.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

The lodge at Davis Quail Hunts

Nobody, however, is fishing. Not today. Wrong season. Things still happen according to the old rhythms in the Black Belt. There is a time when you plant and a time when you pick. You burn the woods once a year, and you hunt turkeys when the dogwoods are blooming. And you hunt birds (aka quail, aka bobwhites) from November, sometime, until February, sometime.

I’ve caught the tail end of that season in the coldest winter anyone can remember. The fire inside the lodge feels good. The big stone fireplace is at one with the rest of the interior. Hardwood floors. Overstuffed furniture. Mounts of deer with heavy racks.

The lodge is run by an affable man named Montgomery Smith. You find yourself immediately at ease in his company and start talking about bass fishing and bird hunting and other essential things.

Smith has hunted these parts all his life, and he remembers a time when bird hunting was a matter of knocking on doors and asking for permission and almost always getting it…and getting some birds. Those days are gone. Farming and forestry practices changed, and the wild bird population declined to the point where it was hardly worth hunting them. Deer hunting came on. So did turkey hunting. The local boys kept hunting; they just didn’t hunt birds much anymore.

But there were plenty of people who missed it. Missed walking behind a couple of big-going dogs, watching as they coursed through the broomweed and then feeling that little thrill when one went on point and the other backed.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

Walking up birds at Shenandoah

So, commercial lodges began to appear. These were places where you could replicate the old experience. The biggest difference was that you hunted what are called planted birds. Or release birds.

They don’t fly as explosively as wild birds, but for people who love the sport, this is not necessarily a deal breaker.

“Good dog work and good ground,” Smith says. “Those things make a lot of difference.”

We go out after lunch and the ground looks just right, if a little damp. We will be walking today, and after the hours spent in airplanes and rental cars, this suits me fine. Walking was the way we hunted them when I was growing up, and it has always seemed the sovereign way of doing it.

The rolling country around Cottonwoods is grown up in broom sage, briars, and islands of pine, scrubby oak, and honey locust. There are a few small plots of tilled ground, planted in millet.

Smith’s dog is a sturdy male pointer.

“Hunt ’em up,” Smith says when he lets the dog off his lead.

Bird hunters say this to their dogs the way that preachers say, “Let us pray” to their congregations. It translates to “Game on.”

Photo: Caleb Chancey

A setter at Shenandoah

The dog gets right to work and he is all business. He dives into the briars and works through thick brush, moving fast but with deliberation. A few minutes later, the dog stops moving as if someone has hit a switch. The dog is motionless except for the soft heaving of his rib cage. He does not flinch as we move in past him. Or when four quail get up, making more noise than seems possible, and angle off toward a stand of pines. I’m slow, then quick, and miss with both barrels. But I have an excuse. I’m shooting a borrowed gun.

I feel, as I always do after a miss, that I have somehow let the dog down. But this one is not dismayed. He picks up the two that Smith has killed and goes back to work. We hear a few distant shots and, briefly, the hum of farm machinery. Otherwise the countryside is quiet and still. We hunt until dark, and we shoot plenty of birds and miss a fair number, too. We stop at one point to admire the ground and the dark prairie soil that is the reason—one of them, anyway—that this region is called the Black Belt.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

1 of 6

Photo: Caleb Chancey

2 of 6

Photo: Caleb Chancey

3 of 6

Photo: Caleb Chancey

4 of 6

Photo: Caleb Chancey

5 of 6

Photo: Caleb Chancey

6 of 6

Quail Economics

The rich alluvial deposits from the region’s several rivers that flooded routinely, before they were brought under control by dams, made this Alabama’s agricultural tenderloin. The rivers that deposited those fine soils also made it possible to move the crops downstream to market. Cotton, of course, was the crop of choice in the early nineteenth century. And with cotton came slave labor.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

Ejecting a spent .410

A large percentage of the population in these parts has always been black. First slave. Then free. Hence, a second definition of Black Belt, the one accepted by people who are not from here and do not know the place or its history.

Many freed slaves moved on after the Civil War, but many also stayed—enough that some counties were majority black. Farming and timber remained the foundation of the economy. Misfortunes—including the destruction of the cotton crop by the boll weevil—followed misfortune until poverty began to seem like the natural condition of the Black Belt.

My education on how bird hunting fits into the picture and might actually bring some economic development to the Black Belt begins back at the lodge, where there is, of course, a bar. After Smith has built up the fire, he pours whiskey and explains.

“It’s about going with what we’ve got,” he says.

That would be great hunting and fishing. Which people will come—and pay—to enjoy. Smith normally has a lodgeful during bird season. “A lot of corporate parties but also people who just love bird hunting and maybe have dogs that don’t get enough work.”

In addition to the bass fishing, an operation like his could put on a dove shoot or two on fields that have been planted and prepared. Or provide a guided turkey hunt. Then, there is the sporting clays course. But bird hunting, here and at several other lodges around the Black Belt, is the real draw.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

Supper Time

A typical meal at Davis Quail Hunts.

The economics are simple enough. Consider Cottonwoods an agricultural enterprise and its chief crop quail. The value added in using an acre of this ground to farm quail is far greater than it would be for soybeans, cotton, or timber. And then there are the benefits to the local economy. Smith buys farm machinery, seed, fertilizer, fuel, and all the other necessities of a farming operation from local suppliers. Somebody has to raise the birds that he releases, and a couple of high school kids have to pluck the birds at the end of a hunt. There is money to be made in all of it.

Adventures in the Black Belt

In the morning, I drive to Davis Quail Hunts near Minter. This operation is run by Colvin Davis, a legendary dog trainer, and his wife, Mazie. It is not quite the size of Cottonwoods. Cozier and more like a family home where you are a houseguest. Colvin is one of those men who are in no hurry, which probably explains his ability with dogs. To work successfully with strong-willed bird dogs, you need patience bordering on serenity. That would be Colvin.

We hunt off a wagon here, which allows us to watch the dogs without distraction. And Colvin’s dogs are worth watching. They move like oil through the cover, and when they make game, they stop so suddenly that it doesn’t quite seem possible.

A little English cocker rides along in Colvin’s lap until someone knocks a bird down. Then she comes down off the wagon and goes to work. She scours the brush until she finds the downed bird, picks it up in her mouth, then hustles back to Colvin’s lap before she drops the bird and waits for praise. Which she always gets.

We shoot all afternoon and the shooting is good. It is always going to be good at one of these places. Or there are always going to be birds, anyway; the shooting part is up to you. I do okay.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

A successful retrieve

We are joined for dinner by Thomas Harris, who has driven from his home in Montgomery to talk about his idea for economic development in the Black Belt. Harris is gracious, almost courtly. At dinner, he tells me about the thinking behind his creation, Alabama Black Belt Adventures.

“People in this part of the state keep waiting for something to happen, hoping for the day when they will get their automobile plant. But that day will never happen.

“So it seemed to some of us that if there was going to be economic development in the Black Belt, it would have to be based on the assets that we already have. We have a wonderful tradition of hunting and fishing on eleven million acres of land that hasn’t been developed and where there isn’t any sprawl and where people can come and experience things that just aren’t available any longer anywhere else.”

He came to the idea after studying perhaps the most celebrated of all the economic development through tourism efforts, not just in Alabama, but anywhere. That, of course, would be the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail.

If it could work for golf, then maybe it could work for bird hunting and maybe it could do something good for the Black Belt, a place he loved and where he had hunted birds all of his life.

“It’s such a beautiful, special place,” he says.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

The rolling hills at Davis

When I ask how it is going, he says he is optimistic. They are just getting started but making progress. There is a Web site that is up, and on it are listed nearly fifty lodges affiliated with Alabama Black Belt Adventures. The state is coming in with money. There are nascent marketing plans. People are getting aboard, and there is momentum behind the project.

Fortunes have been made, in these parts, on recreation. Ray Scott, who founded B.A.S.S. (Bass Anglers Sportsman Society), has a place near here and is involved in the project. So is Jackie Bushman, who founded Buckmasters, the deer hunter’s association based in Montgomery. Harris believes that quail hunting could be the next thing and that, if it is promoted, could do for the Black Belt what pheasant hunting has done for South Dakota and duck hunting has done for Stuttgart, Arkansas.

It may be a stretch. But then, Harris says, the golf trail had plenty of skeptics in the early days. In Alabama, people have seen what can happen, and they believe.

On to Shenandoah

Before he leaves to drive back to Montgomery, Harris says he hopes my hunt the next morning at Shenandoah Plantation will be successful.

Shenandoah is west of Union Springs, a place famous for field trials and bird hunting. Its lodge is the most well-appointed of the ones I visit. The sort of place you could bring a non-hunting spouse with a fondness for comfort.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

Signaling a point

With the owners, Tom and Sue Ellen Lanier, I ride horseback through piney woods and broom sage. There was fog early but it burns off and turns into one of those brilliant late winter days with a high, clear sky and plenty of sunlight, just warm enough that you don’t need a jacket. We admire the day and remark on how fine it is and every few minutes, dismount when the dogs go on point. You could do a lot of things with a day like this, I think, but the inspired way to spend it would be on horseback, hunting birds.

Late in the morning, after we have found perhaps a dozen coveys of birds, I look up to find the source of an unusual call and watch as an adult bald eagle lands on a top branch in a tall loblolly.

We end it at noon and eat a big meal, the kind they called “dinner” way back when. Fried chicken, butter beans, collards, cornbread. I wouldn’t mind a nap but it is time to leave. My gun has been found and after a morning like this, nothing seems impossible except, perhaps, the Atlanta airport.

For more information about Cottonwoods Sportsman’s Lodge (334-628-8693), Davis Quail Hunts (334-412-4904), Shenandoah Plantation (334-321-4992), and many other lodges in the Black Belt of Alabama, visit alabamablackbeltadventures.com.