In January, on a very cold, rainy night not in Georgia (RIP, Tony Joe White) but in Nashville, I took my mother to the Bridgestone Arena to see a star-studded tribute to Willie Nelson, which was heralded as a commemoration of his eighty-sixth year and titled “Willie: Life & Songs of an American Outlaw.” By now the show may well have been broadcast on the A&E channel (as I write the date has not yet been set), and if so, I hope y’all saw it because it was pretty damn amazing. Mama and I are inveterate concertgoers. We’ve seen everybody from Petula Clark and the Carpenters to Edgar Winter’s White Trash (not entirely her idea) to the Rolling Stones. I knew she loved Willie and at least a half dozen of the umpteen folks featured in the show, but the real reason I invited her to go was to see Kris Kristofferson, whom she worships like no other. One summer night years ago, we sat on our Seaside, Florida, front porch with a couple of friends and a boom box and listened to Songs of Kristofferson about 150 times, in tears, naturally. Admittedly, we were fueled by more than one pitcher of frozen peach margaritas (well, actually, they were more like margarita daiquiris because I thought it might be interesting to add a bottle of rum). But you don’t have to be drunk to be equally moved—five of the twelve songs on the compilation are quite simply among the best ever written. In the world. I once asked Chris Gantry (who wrote “Dreams of the Everyday Housewife,” a seriously fine composition its ownself) to name the most perfect, most quintessential country song and braced myself for “He Stopped Loving Her Today” (almost invariably the number-one answer), but he didn’t miss a beat: “Help Me Make It through the Night.” As the kids would say, true dat.

But back to the concert. Chris Stapleton opened with a rousing “Whiskey River.” Next up were Willie’s sons Micah and Lukas, who are perfectly beautiful and super talented (Lukas cowrote eight of the songs in A Star Is Born) and sound exactly like a fifty-years-younger Willie. Nathaniel Rateliff, on the keyboards, did a soul-stirring version of Leon Russell’s “A Song for You,” and Jack Johnson sang a sweet and hilarious tune written for the occasion called “Willie Got Me Stoned.” Gentleman Lyle Lovett (as I’ve decided to call him because he’s clearly so kind and courtly and I have such a crush) did a terrific cover of “My Heroes Have Always Been Cowboys,” and Vince Gill, another of the world’s nicest men, killed “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” And then there were the breakout performances of the night: Alison Krauss singing “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground” and Jamey Johnson doing “Georgia on My Mind.” Now, I have heard both those songs a whole lot of times by a whole lot of people, but Krauss took my breath plain away (along with everybody else’s), and Johnson brought me to my feet (along with the rest of the packed house).

There were a whole bunch of other people, including Jimmy Buffett and George Strait, who had never before sung with Willie—an astonishing fact given that the birthday boy had done duets with everybody from Julio Iglesias to Snoop Dogg, not to mention every other country star in America, and one that Strait lampooned with “I Never Got to Sing One with Willie.” Toward the fourth hour, Willie and Kris did their own duet of “Me and Bobby McGee,” and though Kris’s voice was maybe not what I would term its tip-top best, Mama wouldn’t hear a bad word about him and declared that he looked fabulous to boot. Also, there was the house band, which was worth the not-exactly-cheap price of admission alone. Pulled together by the brilliant producer Don Was, who played bass, it featured the great Matt Rollings on keyboard (he produced Willie’s Summertime album and has played on every single one of Lyle Lovett’s recordings, among countless more), Amanda Shires on fiddle (in a crazy-hot drum majorette outfit, she also did a ravishing duet with her husband, Jason Isbell), and Mickey Raphael on harmonica.

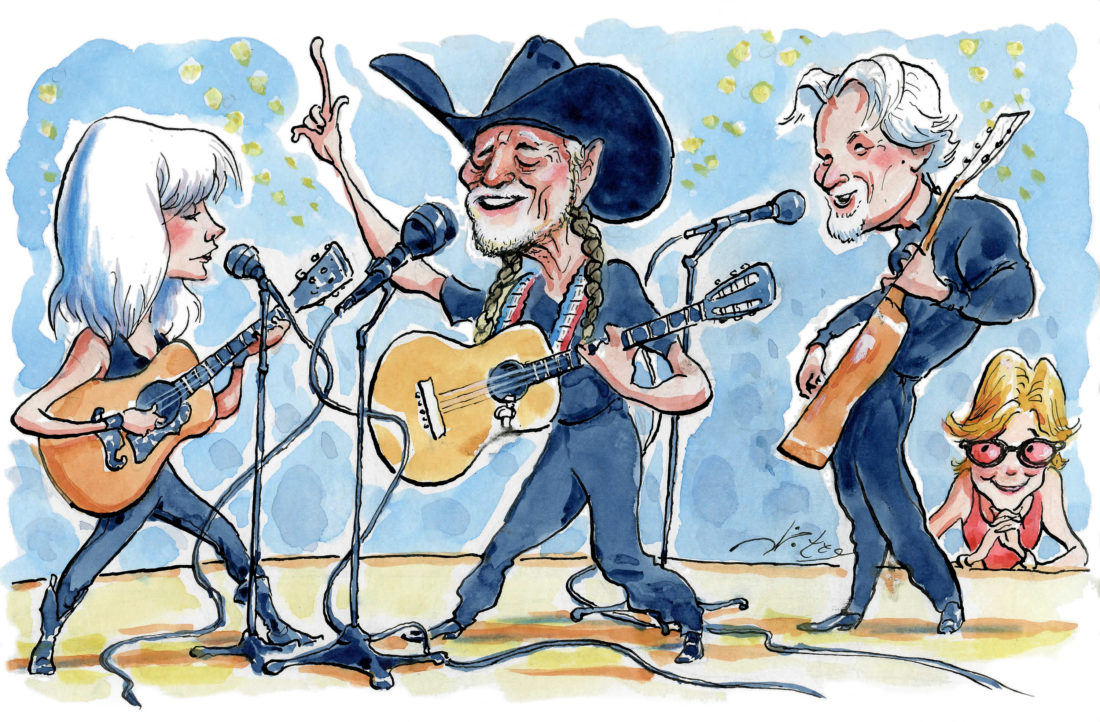

Mickey, who has been playing with Willie for forty-five years, is the hardest-working man in show business. Impeccably dressed, as always, in a slim black suit, he played on all but maybe two songs in the four-and-a-half-hour show. Mama was worried to death about him. Plus, he’d rehearsed for two days, unlike his boss, who does not do much in the way of rehearsing. (I mean, what the hell—he’s eighty-five and he’s long since paid back the IRS; and, you know, he’s Willie.) Which meant that it was a good thing that on the dozen or so songs he sang himself, he had some stellar help, including Emmylou on the great Townes Van Zandt epic “Pancho and Lefty.” By the time he and Stapleton came out with “Always on My Mind” (which, as my mother correctly pointed out, is the lamest love song ever), his pipes had opened up and he and the full ensemble closed things out with rollicking renditions of “On the Road Again” (of course), “Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die,” and “I’ll Fly Away.”

Michael Witte

I first met Mickey on the same day I met Willie and Kris, sometime in the early nineties, on a bus in the bowels of the Superdome during that summer’s Farm Aid. It was a memorable afternoon. We smoked a lot of dope and Kris quoted a lot of William Blake, and Mickey, who now rides the “straight bus” exclusively (yes, there are two buses these days), mentioned that one of his relatives had once owned a watch store in New Orleans, so we went on a stroll down Canal Street to try to find it. I was a guest on the bus, the first of many times, courtesy of my friend Susan Nadler, who really should have her gorgeous mug next to the definition of sui generis in Webster’s. She grew up in Pittsburgh, a self-described Jewish American Princess, and spent time in Israel on a kibbutz and then in a Mexican jail (an experience you can read all about in her book The Butterfly Convention). In Key West, she was a muse of sorts to everyone from the artist Russell Chatham to the poet James Merrill and was married to the aforementioned Chris Gantry. When I first met her, she was starting over again in Nashville doing country music PR, and within a few short years, she and her partner Evelyn Shriver were moguls of sorts, owning George Jones’s record company and producing Soundstage, among their long list of accomplishments.

It was in Susan’s company that I found myself in Tammy Wynette’s kitchen one morning while her husband, George Richey, made us his “prizewinning” biscuits with sausage cream gravy, and in the same kitchen a few years later, Susan and I stood beside Tammy and Leeza Gibbons, as Tammy’s beloved “Meemaw”—in a hospital bed in front of the sliding glass doors overlooking the fan-club weenie roast going on in the backyard—literally breathed her last. We were together on Tammy’s bus when her bus driver claimed a Vietnam flashback, jumped out into a ditch, and took off running. (He later surfaced via a tell-all about Tammy in the National Enquirer, but she, typically, forgave him.) And we were on Willie’s bus once again when a seriously wired Tanya Tucker popped in to say hello to a seriously stoned Willie, Waylon, and Kris, prompting Willie’s deadpan “Man, that girl has a lot of energy.”

I have to confess that I have a bit of a country music connection myself—my maternal great-grandfather was one of the founders of the insurance company, National Life and Accident, that in turn brought the world the Grand Ole Opry (the radio station that to this day broadcasts the Opry every Saturday night is called WSM, which stands for the late company’s motto, WE SHIELD MILLIONS). In those days, unlike now, “society” Nashville did not much mix with country Nashville, though my grandfather, who later headed up NLT, as it became, did play golf with Roy Acuff. I think I was the first member of my extended family to attend the Opry live—my mother was much more of an Elvis girl, though as a child she did have a chocolate-brown cocker spaniel named Goo Goo, after the nutty clusters whose company used to sponsor the show (“Go get a Goo Goo, it’s good”).

But it was with Susan that I learned the real stuff. As in the show must go on—and on. The night Tammy’s mother died, Gibbons offered to go out and greet Tammy’s fans in her stead, but a horrified Tammy wouldn’t dream of it. Not only did she wipe the mascara from beneath her eyes and walk out among the adoring guests, she got on a bus bound for Canada that very same night. As Susan explained, there is still a lurking fear among members of Tammy’s generation especially that they may be one failed record away from landing back in the cotton fields or the beauty parlor or wherever. On her living-room coffee table at First Lady Acres, Tammy kept a bowl of cotton to remind her whence she came. They don’t know how to stop. A year or so before Merle Haggard died, I watched from backstage in Dallas when he opened for Marty Stuart. Such was the state of his lungs that his wife, Theresa Ann, who was also his backup singer, had to continuously leave her post to give him his inhaler. Likewise, in the past eight years, the ever productive and marvelously eclectic Willie has recorded no fewer than eleven albums (bringing his studio album total to sixty-eight), including tributes to George Gershwin, Ray Price, and Frank Sinatra, as well as the aptly titled Last Man Standing.

Such was the breadth and depth of my experiences with Suse over the years that I tried and tried to come up with a way to translate them into a story for Vogue, where I was then employed. I never did, but that did not stop me from using my massive expense account (this was in the long-gone golden era of magazines) to try to figure it out, an exercise that involved multiple trips to Nashville and beyond. At Marty Stuart’s suggestion, I flew to Dallas to interview Hank Williams’s sister Irene just before she died and flew again to Montgomery, Alabama, to attend her funeral with Marty and his wife, Connie Smith. I took the brilliant fashion photographer Arthur Elgort with me to shoot the CMA Awards one year, and then to Fan Fair (where he was forced to protect his cameras in a rainstorm by lying on the dry ground beneath Clay Walker’s bus).

I had wanted to get at the humor and deep-seated humanity of the people I had been lucky enough to spend time with, at their never-give-up gumption, at their all-too-rare lack of bullshit. (When Lorrie Morgan announced her engagement to Clint Black’s bus driver, Susan tried to give the short-lived future husband a tad more gravitas by referring to him in a press release as a “transportation director,” a bit of wordplay Morgan nixed: “Susan, he’s a bus driver. Call him a goddamn bus driver.”) And in some small way I may have wanted to pay tribute to my own roots. Though I didn’t write the piece, at one point during my years-long “reporting,” I was asked to write the liner notes for the Little Jimmy Dickens single “How Much Is That Picture of Jesus.” Dickens, who was the oldest living member of the Opry when he died in 2015, was around in my great-grandfather’s day. I like to think that “Dee Dee,” as my mother called him, would have been proud that at least one family member found her way back home, as it were. And I’m sure he would have been gratified to see us cheering on Willie and the gang, even if his own music of choice was opera.