When I was a boy in Mississippi, my father had a dream to breed Labs for duck hunting, which I very much supported, for up until then, I was the family retriever. He made me slog into icy bayous at sunrise to fetch the dead birds, the water leaking into my gloves and waders, ensuring I would not feel my extremities until Saint Patrick’s Day. I often got stuck in the gumbo and found myself immobile among the decoys as more birds flew overhead.

“Get down, boy!” Pop would whisper across the water. “Here come some more!”

“If I get down, I’ll be underwater,” I’d politely offer.

As Pop would shoot over my head, mallards fell to my left and right as I shut my eyes tight and prepared for death. Later, when Pop announced his plan to train Labs to do the retrieving, I was all in. Let the dogs have it. I wanted to live.

Before long, we had a kennel of bouncing black and brown cuteness. I suggested we bring the puppies inside during cold weather, but Pop felt inside pets were a modern sickness, like food allergies and seat belts. He wanted tough dogs who did not fear cold. They got so tough that when it came time to train, their brains were impervious to command. Each thrown ball got carried off into the woods, never to be seen again, leaving a trove for future archaeologists to theorize about an ancient tribe of Mesoamerican tennis pros.

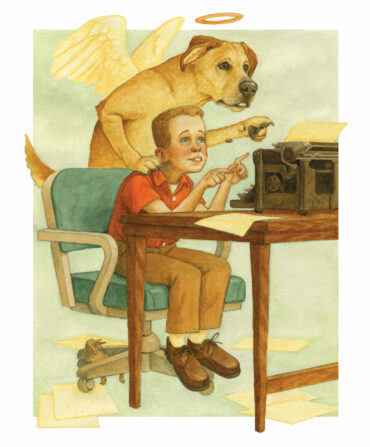

Their one real talent was escape—from every enclosure we could conceive—which often resulted in death-by-pulpwood-truck. I buried many pets before breakfast, shovel in one hand, Pop-Tart in the other. And so I remained the family retriever in the blind. I suppose my father instinctively knew what most men today do not: Whatever doesn’t kill a boy gives him something to write about. As soon as I was old enough, I ran off like all those dogs and never came back. The year I turned forty, I published a book about my father, The World’s Largest Man, just to exorcise the demons and monetize my trauma.

I now live in Savannah, and the only things I hunt are books and reasonably priced bourbon. A couple of years ago, when my daughters and my wife, Lauren, asked for a Lab, naturally I said no. But then COVID hit, and the pandemic broke my brain. This, I tell myself, is why I agreed to the dog. We surprised the girls one afternoon, setting the tiny chocolate beast before them. They wept and called him Gary.

As he grew, this adorable monster devoured all our possessions: jewelry, tea sets, drywall, baseboards, Apple products. Unlike Pop, I allowed the dog to sleep inside, in a crate filled with blankets, which he shredded into strips and consumed like beef jerky. I became a connoisseur of “indestructible” dog beds and would wake to find that Gary had upcycled his indestructible bed into a wearable poncho. We soon launched our training plan, which consisted of buying training books and allowing Gary to eat these books.

By the time he was six months old, I was the only human in the house large enough to walk him. The demons inside Gary could not be tamed: praise, pats, prayers—nothing worked.

“What a big puppy!” neighbors said as Gary threw himself on the ground, wagging his tail, hoping to taste their pants.

We called in a professional trainer, Ben, with his little pouch of treats, to help. He was great—in minutes, he had Gary sitting and staying. It was very upsetting. And as soon as Ben left, Gary shape-shifted back into a ninety-pound gremlin.

Fixing him did not fix him. Feedback from dog sitters read more like police reports:

“FEARS NOTHING.”

“UNRESPONSIVE TO COMMANDS.”

“VIGOROUS NONSTOP HUMPING.”

Like all the dogs of my youth, Gary ran away, for our home has a strange architectural feature known as “doors.” He escaped them all.

In one of the more terrifying instances, I allowed Gary to ride around the neighborhood in the back of my truck, hoping the fresh air would turn him normal. I went about this safely, lashing his leash to a D ring to keep him from jumping out of the truck, to which Gary responded by jumping out of the truck. I was doing thirty when I saw a brown blur leap out and dangle off the side like the world’s largest bass.

“Is your dog okay?” a jogger asked as I jumped from the cab.

“He’s a rescue,” I said, trying not to freak out. I carried Gary into the truck and vowed never again to let him ride in the back without a bodyguard.

He barked when hungry, barked when full. When he’d tire of eating the furniture, he’d lie down at my feet, always touching some part of my body with a paw or his giant bullish head. He was very feely. A sweet dog, if insane.

One day at the dog park, after his usual pillaging, Gary brought me a ball. Instinctively, I threw it. Gary returned seconds later, dropping it at my feet. I threw the ball again. Again, he returned. Oh my Lord, I thought. This dog is retrieving.

The next day, I took him to an empty lot. I threw the rubber ball at least eighty yards and he took off. We did this for an hour, with perfect retrieval every time. In an instant, his demons had been purged, along with a few of my own. Gary had miraculously transformed into a superstar retriever, the envy of other owners, who stopped and stared in awe.

Now Gary no longer leaps from speeding trucks and only occasionally escapes the house, though he can be coaxed inside if you cover your body in Jif Creamy and lie in the doorway screaming. I don’t know why Pop could never train those puppies or why Gary is different. Maybe it’s the blankets we allow him to eat, or how we let him hurl his ninety pounds of muscle onto the bed at nap time, the way my father never would.

One winter day when Gary was about to turn two, I took him, as I do every day, to our little park at dusk, wet and cold. We don’t mind the rain and mud. The older I get, the more I long for the familiar discomforts of my childhood.

Gary sat at my feet, waiting, and I rewarded him with a treat from my little pouch, which in some other life would’ve held waterfowl shot. I squinted at the darkening sky and imagined I stood at dawn on a spit of soft wet earth in the Mississippi Delta, Pop to my left, scanning the horizon. It took me so long to see that my father never really cared if those dogs retrieved. He just wanted to hunt with his boy and give him a life worth writing about. I buried him and I will have to bury this beautiful dog one day, too. But not today. No, on that day, my four-legged son and I stood under a sky as wide as time. I held the launcher in my hands like a Browning and let the ball fly and Gary shot off and came back in a blur, dropping the ball at my feet.

“Good boy,” I said, kissing his big brown head.

Everything good comes back, if you give it time.